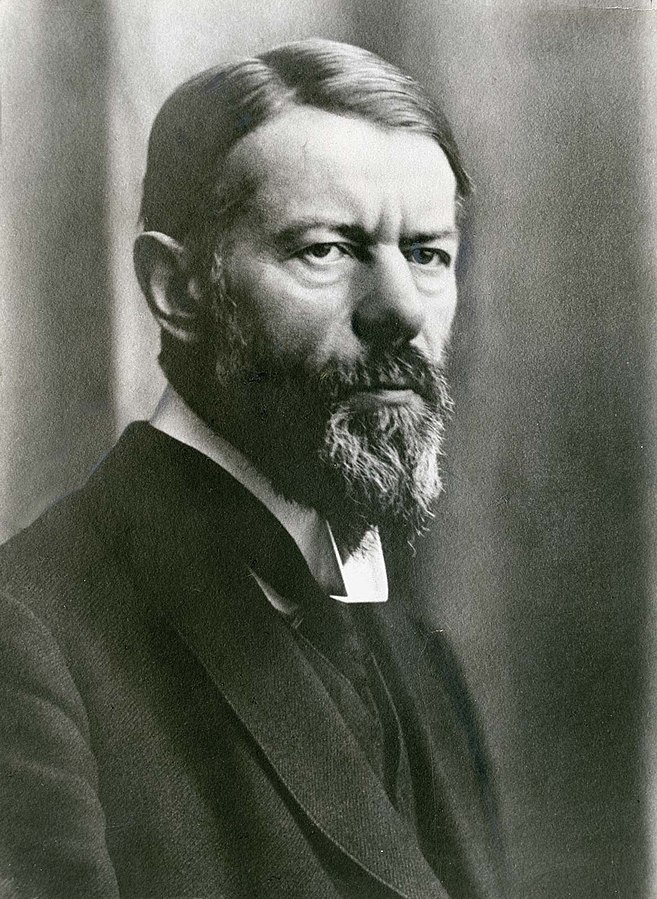

Brief Biography:

Max Weber, born in 1864 in Erfurt, Prussia, was the eldest of eight children in a well-off family marked by contrasting beliefs. His mother was deeply religious and a devout Calvinist, while his father was indifferent to religious matters, dedicating his time to politics. Their home served as a gathering place for politicians and academics.

Despite being a mediocre student, Weber was an enthusiastic reader, delving into philosophy, history, and classics. In 1882, he began studying law at Heidelberg University, later pursuing studies at various Prussian universities. In 1886, he obtained a law license, followed by a doctorate in 1889. Instead of practicing law, he pursued scholarly interests, collaborating with diverse scholars.

Weber’s academic pursuits were disrupted by military service and an active social life, including his engagement with Emmy Baumgarten, which ended due to her mental health issues. In 1893, he married his distant cousin, Marianne Schnitger, who played a pivotal role in his academic work while pursuing her own causes.

A quarrel with his father in 1897, followed by his father’s death, led to Weber’s struggle with mental health issues, causing him to withdraw from teaching in 1903. He eventually returned to teaching in 1918.

During World War I, Weber served in logistical roles due to his age and underwent a transformation from supporter to critic of German expansionism. Post-war, he became deeply involved in politics while continuing his academic pursuits. Weber passed away on June 14, 1920, due to pneumonia.

Max Weber stands as one of the most prolific classical sociologists, addressing topics such as religion, politics, power, and the economy through present observations and historical study. His wide-ranging contributions continue to shape sociological thought.

Weber’s Protestant Ethic and Spirit of Capitalism:

Written in 1904 and 1905, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism is Max Weber’s most well-known work. It explores the relationship between the development of capitalism in Europe and the Reformation, particularly focusing on the rise of Protestantism, namely Calvinism. Contrary to Karl Marx’s view, which attributes the emergence of capitalism to material or economic circumstances, Weber posits that ideas, especially religious doctrines, were essential in shaping and spreading capitalism as Europe’s primary economic system.

Weber defines the ‘spirit of capitalism’ as the continuous growth of capitalism through rational activities, notably the constant reinvestment of capital for growth. This includes the creation of a more rationalized capitalist system with developments like quantitative bookkeeping, a clear division of labor organized into a hierarchy, explicit rules, impersonality among workers, and labor structured around technology. Importantly, the ‘spirit of capitalism’ is not just the practice of these activities but a broader attitude that promotes them.

Weber argues that this attitude was deeply embedded in the growing Protestant movement, especially Calvinism, which he believed possessed values and attitudes distinct from other religions and Christian denominations. For instance, while the Old Testament God focused on an ascetic life and the New Testament God regarded worldly activity with indifference, Calvinism’s belief in predestination was markedly different.

Predestination is based on the belief that an all-knowing God has predetermined who will be saved or damned. Since individuals cannot influence their salvation, Calvinists believed that a small group was predestined for heaven. This led to the question of how to identify the chosen ones. Calvinists held that self-confidence in one’s status as chosen, evidenced by worldly success, was a marker. This success was fostered through the Protestant Work Ethic, whose characteristics include, but were not limited to:

- Hard Work and Diligence: Central to the Protestant Work Ethic is the value placed on hard work. Diligence in one’s labor is seen not just as a means to economic gain but as a moral virtue, reflecting a commitment to duty and responsibility.

- Asceticism and Abstinence from Physical Pleasure: This ethic promotes a lifestyle of moderation and self-denial, particularly in terms of abstaining from indulgences and pleasures. This restraint is viewed as a sign of moral strength and discipline.

- Thriftiness and Frugality: Emphasis is placed on saving and careful management of resources. Extravagance and wastefulness are frowned upon, with a focus instead on living modestly and within one’s means.

- Reinvestment and High Savings Rate: The Protestant Work Ethic encourages the reinvestment of profits back into one’s business or work, rather than spending on personal pleasures. This reinvestment is seen as a way to further one’s work and, by extension, fulfill one’s duty.

- Rational Approach to Work and Life: This ethic values a methodical and systematic approach to work. Planning, organization, and a rational assessment of tasks and goals are key components.

- Personal Calling and Vocationalism: Work is seen as a calling from God, with each individual having a specific role or vocation to fulfill. This spiritualizes work and integrates it with one’s religious and moral life.

These traits not only shaped individual Calvinists’ worldly successes but also correlated with the emerging capitalism of the time.

While the Protestant Ethic was vital in creating and sustaining capitalism, Weber concludes that capitalism became secularized as it evolved into a global system. He argues that ‘the technical and economic conditions of machine production’ took precedence over the religious motivations for work. Over 70 years later, sociologist Daniel Bell, in The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (1976), posited that by the late 20th century, the Protestant Ethic had been completely supplanted by what he termed the ‘Hedonistic Ethic.’ This ethic, contrasting starkly with the Protestant Ethic, is characterized by the following characteristics:

- Pursuit of Pleasure and Leisure: Unlike the Protestant Ethic’s focus on hard work and asceticism, the Hedonistic Ethic prioritizes personal enjoyment and leisure activities. This shift reflects a societal move towards valuing immediate gratification and sensory experiences.

- Consumerism: Bell notes a transition from a culture of saving and reinvestment (key aspects of the Protestant Ethic) to one dominated by consumption and immediate gratification. In this context, success and happiness are often measured by the ability to consume and possess material goods.

- Throw-Away Culture: This ethic fosters a culture where products and experiences are disposable. Instead of the thrift and careful stewardship of resources promoted by the Protestant Ethic, the Hedonistic Ethic encourages a continuous cycle of consumption and discarding.

- Anti-Science or Professionalized Science: There’s a shift in the perception of science. Where the Protestant Ethic encouraged a fascination and exploration of God’s creation (which could include scientific endeavors), the Hedonistic Ethic either views science with skepticism or reduces it to a mere profession devoid of deeper ethical or philosophical implications.

In conclusion, Weber’s analysis of the Protestant Ethic and its role in the development of capitalism highlights the complex interplay between religious beliefs and economic practices. His work, juxtaposed with Bell’s later analysis, underscores the dynamic nature of societal values and their profound impact on economic systems. As capitalism evolved from a system rooted in religious ethics to one driven by hedonistic values, it reflects the changing priorities and cultural shifts within society, raising critical questions about the sustainability and future trajectory of capitalist economies.