Table of Contents

- Learning Objectives

- Introduction

- What is a Social Construction? Exploring How Society Creates Meaning

- What is a Social Category? Understanding Identity and Social Meaning

- What are Social Institutions? How Society Organizes Stability

- What are Social Structures? Understanding the Hidden Patterns of Society

- Conclusion

- Key Terms

- Module Summary

- Apply What You’ve Learned

- Check Your Understanding

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, students will be able to:

- Define and distinguish between key sociological concepts: social constructions, social categories, social institutions, and social structures.

- Explain the process by which social constructions gain meaning and become “naturalized” in everyday life.

- Identify examples of social constructions (e.g., money, marriage, graduation) and analyze how they influence social behavior and expectations.

- Describe major social categories such as race, class, gender, age, ethnicity, and sexuality, and understand how these categories shape individual and group experiences.

- Apply the concept of intersectionality to explore how overlapping social categories influence unique lived experiences.

- Recognize the functions and roles of major social institutions (family, education, economy, religion, politics) in maintaining societal stability and transmitting values.

- Differentiate social structures from institutions and explain how underlying social patterns organize relationships and social roles.

- Reflect on how abstract sociological concepts are present in familiar settings and professional contexts such as schools, hospitals, and local communities.

Introduction

Sociology invites us to look beyond our personal experiences and ask bigger questions about how the world around us works. In the last module, you learned that sociology is defined as the study of social relationships between two or more people and how those relationships solidify into social constructions, categories, institutions, and structures. In this module, we take a closer look at each of these key ideas.

Some of this may feel confusing at first. That is normal. Sociology often challenges what feels like common sense and asks us to look at familiar things in new ways. Feeling unsure does not mean you are doing poorly. It usually means you are learning to think differently.

Think of this module as the foundation of your sociological toolbox. The ideas you learn here will come up again throughout the course. Whether you plan to work in nursing, criminal justice, human services, or another field that serves the public, these tools will help you better understand the social forces that shape your life and the lives of others.

Every society has patterns for how things are done. This includes how we define family, organize schools, share money, and decide what success looks like. These patterns do not happen by accident. They are shaped by social constructions, social categories, social institutions, and social structures. These terms may sound new now, but they describe real forces that affect everyday life.

Social institutions are organized systems, such as family, education, and government, that meet important needs in society. Social categories group people based on shared traits, such as age, race, gender, or class. Social constructions are ideas and practices that exist because people agree they have meaning, like weddings, money, or laws. Social structures are the often unseen patterns that shape roles, relationships, and expectations across society.

Together, these ideas help explain how our social world works. In this module, you will learn how they shape daily life and influence who we are and how we relate to others. Learning to recognize these forces helps you think more clearly about your own experiences and better understand the communities and institutions around you.

What is a Social Construction? Exploring How Society Creates Meaning

Have you ever stopped to ask why a graduation ceremony feels important. Why a wedding makes a lifelong promise feel official. Or why a dollar bill can be exchanged for food or clothing. These are everyday parts of life, yet we rarely pause to think about where their meaning comes from. Sociology invites us to step back and ask an important question. What if the meanings we take for granted are not natural, but created by society.

This is where the idea of social constructions comes in. In sociology, a social construction is something that exists because people agree that it does. It gains meaning because we treat it as real through shared beliefs and actions. Social constructions like graduations, weddings, and money do not have power on their own. They have power because people give them power and act as if they are real.

Understanding social constructions is an important part of learning to think sociologically. When we realize that many parts of our world are created by people, we begin to question what we often call common sense. What feels obvious or natural may actually be the result of long standing social agreement. For example, there is not just one way to hold a wedding or use money. Different cultures and different time periods have done these things in very different ways. What we think of as common sense often reflects the values of those with the most influence in society.

Social constructions matter because they shape how we live, what we value, and how we treat others. They influence how we celebrate success, how we define relationships, and how we exchange goods. They also help show whose values are accepted and whose are ignored. In this way, social constructions are not only about shared meaning, but also about power.

To make this process clearer, we can look at four stages that show how social constructions become part of everyday life.

- First is agreement on reality. A group comes to a shared understanding that something matters. For example, people agree that finishing school is important.

- Next is social definition. The group decides how to give that idea meaning. Graduation ceremonies, with caps and gowns, become the way to mark school completion.

- Then comes continued maintenance. The meaning stays alive through repeated actions, such as schools holding ceremonies and families celebrating them each year.

- Finally, there is naturalization. Over time, the idea becomes so accepted that it feels like it has always existed. We stop questioning it and see it as a normal part of life.

Now let’s look at some familiar examples.

Graduation did not always involve a formal ceremony. Over time, societies decided that finishing school should be recognized. Traditions like gowns, speeches, and diplomas were created to mark the moment. Schools and families repeat these traditions year after year, reinforcing the value of graduation. Eventually, it becomes expected. For many students, graduation feels natural, even though it is a social creation.

Marriage is another example of a social construction. People across cultures see it as meaningful, but the way it is defined and celebrated varies widely. Some view it mainly as a religious bond. Others see it as a legal agreement. Many see it as both. Traditions, laws, and expectations help keep marriage recognized as an important part of social life. Over time, it becomes so familiar that many people see it as a necessary step in adulthood rather than something created by society.

Money may feel like the most real example of all, but it too is a social construction. Money only has value because people agree that it does. A piece of paper or a number in a bank account has no natural worth on its own. But through shared belief and government regulation, we treat it as valuable. Because of this, money becomes a normal and unquestioned part of everyday life.

When we understand how social constructions form, we begin to see the world differently. We realize that many things we take for granted are not fixed or natural, but created and maintained by people. This helps explain why societies have different customs and why change is always possible. More importantly, it encourages us to think more carefully about the ideas we accept without question and to imagine new ways of doing things.

What is a Social Category? Understanding Identity and Social Meaning

In the last section, we looked at how shared beliefs shape social constructions, ideas and practices like weddings, graduations, and money that feel natural but are actually created and maintained by society. Now we turn to something just as familiar, the traits we use to describe ourselves and others. Think about how quickly we notice people’s appearance, speech, clothing, or behavior. These judgments often happen without much thought, yet they shape nearly every interaction we have. In sociology, we call these groupings social categories.

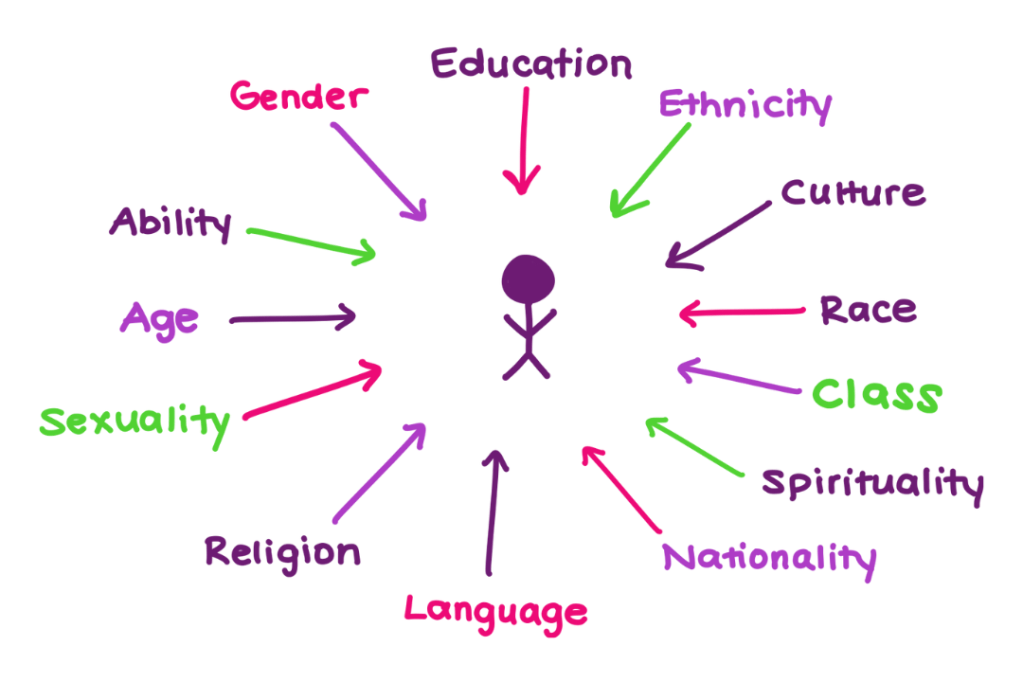

A social category is a group of people who share traits that society considers meaningful. Examples include age, gender, race, class, ethnicity, and sexuality. These categories shape expectations, roles, and life experiences. They are not just labels. They are powerful ways that society organizes people, often influencing how individuals are treated and how they understand themselves.

It is important to remember that categorization itself is a social construction. The categories we use and what they mean are not fixed by nature. They are created, defined, and maintained by societies. The traits we focus on and the meanings we attach to them reflect shared beliefs. This is why social categories can change over time and across cultures, and why different societies group people in different ways.

The categories listed here are not the only ones that matter. They are simply some of the most widely recognized in many societies today. In your own community, workplace, or culture, other categories may be just as important. Part of developing a sociological perspective is learning to notice these systems of classification and to question how they shape people’s experiences and opportunities.

Like social constructions, social categories are deeply woven into everyday life. They affect not only how we see others, but also how others see us. By studying social categories, sociology helps reveal the often unseen ways that society organizes people and assigns value based on group membership.

In the next sections, we will look more closely at several major social categories. We will also introduce the idea of intersectionality, which helps explain how different categories overlap and interact to create unique experiences.

Types of Social Categories

In this section, we explore several common social categories that strongly shape people’s lives. As you read, remember that these categories are not biological facts or unchanging truths. They are social ideas, created and maintained through shared beliefs and behavior. Their meanings can change over time and differ across cultures. These categories influence how people understand themselves and how they are treated by others.

Race

Race is one of the most visible and powerful social categories. It is often linked to physical traits like skin color, facial features, and hair texture. But the meanings attached to these traits are created by society, not biology. Categories such as White, Black, Indigenous, or Asian reflect social ideas about difference, not scientific facts. These ideas have been used in the past to justify unequal treatment, and they still affect how people are viewed today. Race can shape everyday interactions as well as opportunities in education, work, and healthcare. It also influences how people see themselves and where they feel they belong.

Ethnicity

Ethnicity refers to shared culture. This can include traditions, language, ancestry, religion, or food. While race is often assigned by others, ethnicity is more closely tied to cultural identity. A person might identify as Irish-American, Haitian, or Palestinian based on family history and cultural practices. Ethnic identity can create a strong sense of belonging, but it can also be a source of misunderstanding or exclusion. Like race, ethnicity is shaped by history and social context, and it can change across generations.

Class

Social class refers to a person’s place in the economic system. It is often connected to income, wealth, education, and occupation. Class influences where people live, the kind of healthcare and education they receive, and the opportunities they have. It also shapes how people are treated by others. Class is not only about money. It includes expectations and assumptions that society connects to economic status. Like other categories, class is socially defined, and its meaning can change over time and place.

Gender

Gender refers to the roles, behaviors, and identities society connects to being male, female, or somewhere in between. It is often confused with biological sex, but gender is shaped by culture and social expectations. From a young age, people learn what is considered appropriate for boys and girls, and these expectations influence clothing, interests, careers, and relationships. Some people feel their gender matches the sex they were assigned at birth. Others identify as transgender, nonbinary, or gender-fluid. Gender affects how people are treated, the choices they are offered, and how they understand themselves.

Age

Age is a social category that shapes expectations at different stages of life. Society assigns roles based on age, such as being a student, a worker, or a retiree. These roles are not natural. They are created by laws, policies, and social norms. Age affects how people are viewed and treated, whether they are seen as too young to understand or too old to matter. These judgments shape people’s opportunities and their sense of value in society.

Sexuality

Sexuality includes both sexual orientation and identity. It refers to who a person is attracted to and how they express that attraction. Categories such as heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, and pansexual describe different experiences of attraction. Like gender, sexuality is shaped by social expectations. Different societies define and accept sexual identities in different ways. Messages from family, media, religion, and schools all influence how people understand sexuality. This makes sexuality not only personal, but deeply social.

Each of these categories helps shape how we move through the world, how others respond to us, and how institutions treat us. In the next section, we will explore intersectionality, a framework that helps explain how these categories overlap in complex and meaningful ways.

The Importance of Intersectionality

As we explore social categories like race, gender, and class, it becomes clear that people do not experience society through just one category at a time. Most of us live at the intersection of many identities. A person may be a woman, Latina, working class, and disabled. Each of these traits can affect how she is seen and treated. More importantly, they do not act separately. They come together to shape a unique social experience.

This is the main idea behind intersectionality. In sociology, intersectionality is a framework used to understand how different social categories interact and influence one another. It helps us see how advantages and disadvantages overlap in real life. Instead of looking at race, gender, or class as separate experiences, intersectionality shows how they work together at the same time.

The term intersectionality was introduced by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in the late 1980s. She used it to explain how the experiences of Black women were often ignored by systems that treated racism and sexism as separate issues. Crenshaw argued that we cannot fully understand inequality if we only look at one identity at a time.

This idea can feel challenging at first. Some people worry that it focuses too much on difference or creates division. But intersectionality is not about dividing people. It is about understanding complexity. Each of us lives within many social forces at once. Recognizing that reality helps us better understand ourselves and others. It also helps people in fields like nursing, criminal justice, and human services see how identity shapes access to care, safety, opportunity, and respect.

Let’s look at an example. A student who is both low income and LGBTQ+ may face different challenges in school than a student who is low income but heterosexual. The difference is not only about money or identity by itself. It is about how those parts of identity come together. Intersectionality helps us see the full picture.

Using an intersectional perspective helps sociologists and professionals do several important things. It helps them understand how systems like racism, sexism, and class inequality overlap. It helps them recognize which groups may face multiple barriers at the same time. It helps them notice where policies, services, or protections fall short. And it helps them avoid one size fits all solutions to complex social problems.

In the end, intersectionality encourages us to ask deeper questions. Who is included. Who is left out. Whose experiences are being recognized, and whose are being overlooked. These are not just academic questions. They matter for anyone who wants to build communities that are fair, inclusive, and responsive to real human needs.

As we move forward in this course, we will continue to use intersectionality as a tool for deeper understanding and empathy. It helps reveal patterns that might otherwise remain hidden and gives us language to talk about inequality in clearer ways. With this foundation, we now turn from individual identities to the larger systems that shape society. These systems, called social institutions, organize relationships, guide behavior, and help maintain the structure of social life.

What are Social Institutions? How Society Organizes Stability

As we move from looking at social categories and how they shape people’s lives, we now turn to another powerful force in society, social institutions. These are the organized systems that guide behavior, set expectations, and help meet the shared needs of a community.

To start, imagine a society without schools, families, governments, or religious organizations. Without these systems, daily life would feel uncertain and unorganized. Social institutions create structure. They help societies function by bringing order to relationships and offering support to individuals.

Each social institution has two connected parts that work together to shape how it operates.

Material elements. These are the physical parts of an institution. They include buildings, tools, documents, and rules. For example, a school includes classrooms, textbooks, desks, and attendance records. A government includes courthouses, voting machines, citizenship papers, and official policies.

Ideals and values. These are the shared beliefs that give the institution meaning and purpose. While material elements are easy to see, these ideas guide how the institution works. Schools are based on the belief that education matters and should be available to students. Families are shaped by ideas about care, responsibility, and support. Governments are built on values such as justice, equality, or authority, depending on the society.

Both parts are necessary. Without physical structures, institutions cannot function. Without shared values, those structures would have no direction or purpose.

Studying social institutions is important in sociology because they show how society is organized and how order is maintained. Institutions shape behavior, influence relationships, and help people understand their roles within a larger community.

It is also important to remember that institutions are not the same everywhere. What counts as a family or how a government operates can look very different across cultures and time periods. Institutions change as societies change. For example, family life may shift as cultural values evolve, and schools may adapt as technology and work demands change. By comparing institutions across places and history, sociologists learn how societies respond to new challenges.

In addition to organizing society, institutions shape identity. Through socialization, institutions teach people the values, rules, and behaviors expected in their community. Schools do more than teach subjects. They help students learn how to follow rules, work with others, and understand social expectations. Families introduce children to their first roles and relationships, shaping how they see themselves and others.

Social institutions, then, are not just background systems. They influence how we live, what we believe, and how we connect with others. Understanding them helps us see how society works and how individual lives are linked to larger social forces.

In the next section, we will look at five major social institutions, economy, politics, religion, education, and family, and explore how each one shapes daily life and helps structure society.

The Five Social Institutions

Now that we understand what social institutions are and why they matter, we can look more closely at five core institutions that shape society, the economy, politics, religion, education, and family. These institutions are not separate from everyday life. They affect how we live, how we relate to others, and what opportunities we have.

The Economic Institution

The economic institution shapes how goods and services are produced, shared, and used. This includes everything from jobs and wages to banks and trade.

Different societies organize their economies in different ways. In capitalism, most businesses are privately owned and compete in the marketplace. In socialism, the government often plays a larger role in sharing resources to promote equality. In some societies, people exchange goods directly through bartering instead of using money.

Material elements of the economy include money, banks, credit cards, factories, stores, and online marketplaces. The values behind these systems often include ideas like fairness, profit, productivity, or cooperation.

The economic institution matters because it affects nearly every part of daily life, including where people work, what they can afford, and how wealth is shared in society.

The Political Institution

The political institution is how societies organize power and make decisions. It creates laws, enforces rules, and shapes people’s rights and responsibilities.

Governments take many forms. In democracies, people elect leaders to represent them. In monarchies, leadership may pass through a royal family. In authoritarian systems, power is held by a small group and public participation is limited.

Material elements include government buildings, voting systems, legal documents, and citizenship records. The values behind political systems often include justice, security, freedom, or authority.

Political institutions help maintain order and manage conflict. They influence how resources are shared and how power is distributed.

The Religious Institution

The religious institution brings people together around shared spiritual beliefs and practices. It helps individuals and communities find meaning, guidance, and connection.

Religious traditions include Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, and many Indigenous belief systems. These traditions may involve worship services, rituals, sacred texts, and religious leaders.

Material elements include places of worship like churches, mosques, temples, and synagogues, along with objects such as prayer books and religious symbols. Religious values often include compassion, service, forgiveness, or obedience.

Religion plays an important role in shaping culture and identity. It can bring people together, influence politics and laws, and offer support during difficult times.

The Educational Institution

The educational institution passes knowledge, skills, and values from one generation to the next. It prepares people to take part in society and develop their potential.

Education takes many forms, including public schools, colleges, homeschooling, and job training programs. Different societies may focus on different goals, such as creativity, discipline, or preparing students for work.

Material elements include classrooms, textbooks, tests, and technology. The values behind education often include opportunity, achievement, equality, and citizenship.

Education is not only about learning facts. It also teaches young people how to follow rules, work with others, and understand their place in society.

The Family Institution

The family institution is often the most personal and foundational. It connects people through relationships like marriage, parenting, adoption, and kinship.

Families come in many forms, including nuclear families, extended families, single-parent households, and chosen families. Each reflects different social, cultural, and economic values.

Material elements include homes, family photos, shared meals, and household tools. Family values often emphasize love, care, loyalty, responsibility, and tradition.

Families provide emotional support, teach social roles, and help people develop their first sense of identity. For many, family is where they first learn how to relate to others and what it means to belong.

***

Together, these five institutions form the foundation of social life. They are closely connected to one another and to everyday experiences. Understanding them helps us see how society is organized and how personal lives are shaped by larger systems.

What are Social Structures? Understanding the Hidden Patterns of Society

Think back to the halls of a high school. You might notice friend groups forming, students showing respect to teachers, or classes being separated by grade level. No one hands out a rulebook explaining these behaviors, yet most people follow them. These unspoken expectations are part of what sociologists call social structure.

Social structure refers to the patterns that shape how people relate to one another and to society. These patterns include roles, relationships, routines, and norms. They help create order and make daily life more predictable. Social structures influence who has authority, how people act in different settings, and what roles they are expected to fill.

It can help to compare social structure to something familiar. If a social institution is like a school building with its staff, schedule, and purpose, then social structure is like the blueprint that shows how everything is organized. Social structure is not a place or an organization. It is the system of rules, relationships, and expectations that guides behavior across many parts of life.

This idea may seem abstract at first, but it becomes clearer with real examples. In a high school, structure shows up in how students are grouped by grade, how teachers hold authority, and how routines like class schedules are followed. These patterns shape how people interact and where they fit in. The same kind of structure exists in workplaces, hospitals, churches, and families. We often think of these patterns as just the way things are, but they are created and reinforced by society over time.

Studying social structure helps sociologists understand how societies stay organized and how people learn their place within them. It points to the unseen forces that shape decisions, opportunities, and relationships. While individuals make choices, those choices are often influenced by the structures around them.

For example, social structure helps explain why some groups have easier access to education or jobs while others face more obstacles. It also helps us see how power, privilege, and inequality continue over time. By noticing these patterns, sociologists can better understand how change happens and what might be needed to create more fairness and opportunity.

Social structure may be less visible than social institutions or social categories, but it is just as important. It helps us understand how society works behind the scenes. By learning to recognize these hidden patterns, we can better understand both individual behavior and larger social outcomes. This understanding is especially useful for students entering fields like criminal justice, nursing, or human services, where knowing people’s social environments is key to helping them well.

Conclusion

This module includes some of the most challenging ideas in the course. The concepts you learned here, social constructions, social categories, social institutions, and social structures, ask you to think about everyday life in a new way. Instead of seeing the world as simply natural or fixed, sociology encourages you to look at how meaning is created, how people are organized, and how larger systems shape what we often take for granted.

By working through this material, you have begun to build your sociological toolbox. You learned how shared beliefs turn into social constructions, how categories like race and gender shape people’s experiences, and how intersectionality helps explain overlapping identities. You also explored the major institutions that bring order to society and pass down values, as well as the social structures that guide behavior and expectations. These tools help you see how individuals and groups are shaped by forces that are often invisible but very powerful.

Together, these ideas form the foundation of sociological thinking. You will return to them throughout the course as you use this toolbox to understand real-world issues and professional situations. Whether you plan to work in nursing, criminal justice, or human services, these concepts will help you better understand the communities you serve and the systems you work within.

Key Terms

Age: A social category related to the expectations and roles that societies assign to individuals at different stages of life.

Class: A social category defined by a person’s socioeconomic position, including income, education, wealth, and occupation, which influences access to resources and opportunities.

Economy: A social institution that organizes the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services within a society.

Education: A social institution focused on the transfer of knowledge, skills, and cultural values across generations.

Ethnicity: A social category based on shared cultural traditions, language, ancestry, and heritage.

Family: A foundational social institution made up of individuals connected through blood, marriage, or adoption, responsible for emotional support, socialization, and cooperation.

Gender: A social category related to cultural expectations, roles, and identities associated with femininity, masculinity, and gender diversity.

Intersectionality: A concept describing how overlapping social categories such as race, gender, and class combine to shape unique experiences of privilege and discrimination.

Politics: A social institution responsible for governance, decision-making, law creation, and the organization of power in society.

Race: A social category often based on perceived physical traits that society uses to assign meaning and structure social interactions.

Religion: A social institution that organizes shared spiritual beliefs, practices, and moral systems, often providing a sense of meaning and community.

Sexuality: A social category that includes sexual orientation and identity, influencing how individuals express attraction and form relationships.

Social Categories: Groupings based on shared characteristics such as race, class, gender, or age, which influence individual identities and social dynamics.

Social Construction: A concept or practice that exists because people collectively agree it does, assigning meaning through shared norms and behaviors over time.

Social Institution: A stable and organized system that meets collective needs by combining physical elements with shared values and guiding social behavior.

Social Structure: The overarching system of organized roles, relationships, and institutions that shape social behavior and maintain order.

Sociology: The study of social relationships between two or more people and how those relationships solidify into social constructions, categories, institutions, and structures.

Module Summary

In this module, you explored some of the most foundational and challenging concepts in sociology. You learned how social constructions, social categories, social institutions, and social structures shape both individual experiences and the organization of society. These concepts form the sociological toolbox you will continue to use throughout the course. Together, they help us understand how meaning is created, how people are classified, how systems function, and how roles and behaviors are organized. Whether you are preparing for a career in nursing, criminal justice, human services, or another field, these tools will help you think critically about the social forces that affect the people you serve and the systems you work within.

Apply What You’ve Learned

Now that you have developed a stronger sociological foundation, think about how these concepts appear in your daily life and future profession. How do social constructions shape the way people understand success, health, or responsibility in your community? How do social categories affect who gets heard, who gets help, or who gets left out? How do institutions like schools, courts, or hospitals support or limit people in your area? And how do invisible social structures shape what people expect of themselves and others? Begin to notice these patterns in the places you live, study, and work. The more you apply these ideas, the more useful your sociological toolbox will become.

Check Your Understanding

Use the questions below to review the key concepts from this module. These are designed to help you reflect on what you’ve learned and prepare for assessments. Be ready to answer each one in your own words, using specific ideas and terms from the reading.

- What does it mean to say that “money,” “graduation,” or “marriage” are social constructions, and how does this change the way we understand their importance in our lives?

- What does it mean to say that categories like race, class, and gender are socially constructed, and how does this challenge what we think is “normal” or “natural”?

- What is intersectionality, and why is it important to understanding how power and inequality operate in society today?

- How do social structures shape behavior in ways we do not always notice, and why does sociology emphasize their role in everyday life?