Table of Contents

- Learning Objectives

- Introduction

- Émile Durkheim and the Study of Suicide: Understanding Society Through Social Facts

- Karl Marx: Understanding History Through Class and Conflict

- Max Weber: The Moral Foundations of Capitalism

- Conclusion

- Key Terms

- Reflection Questions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, students will be able to:

- Explain the historical context that influenced the development of classical sociological theory, including the effects of industrialization, urbanization, and social upheaval in the 19th century.

- Summarize the key theoretical contributions of Émile Durkheim, including his concept of social facts, his typology of suicide, and his role in establishing sociology as a scientific discipline.

- Apply Durkheim’s theories to modern social issues such as mental health, social integration, and collective norms, demonstrating the relevance of his work today.

- Describe Karl Marx’s theory of historical materialism, including the concepts of the economic base and superstructure, class struggle, and the stages of social development (slavery, feudalism, capitalism, socialism, and communism).

- Analyze the contradictions within capitalism as identified by Marx and explain how these tensions contribute to social change and inequality.

- Identify Max Weber’s main contributions to sociological theory, particularly his analysis of the Protestant ethic and its role in shaping the spirit of capitalism.

- Compare Weber’s cultural explanation of capitalism with Marx’s materialist perspective, highlighting the role of ideas, values, and rationalization in economic development.

- Evaluate the ongoing influence of Durkheim, Marx, and Weber on modern sociological thought, particularly within the frameworks of structural-functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism.

- Apply classical theory to contemporary issues, such as economic inequality, work culture, and social integration, using insights from all three thinkers.

Introduction

Why do some people thrive in times of social upheaval while others struggle? Why does inequality persist in societies that strive for fairness? And how do cultural values influence the way we work, spend, and live? These are not just abstract questions—they are deeply relevant to understanding the world around us. Sociology provides tools to tackle these questions, and at its foundation lie the groundbreaking ideas of three thinkers: Émile Durkheim, Karl Marx, and Max Weber.

In the last module, we explored the three major theoretical perspectives that shape sociological thought: structural functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism. These perspectives help us interpret society as a system of interdependent parts, as a space of power struggles, and as a collection of shared meanings created through interaction. But where do these perspectives come from? To fully understand their origins and relevance, we need to look back to the foundational theorists who set the stage for sociology as a discipline.

Durkheim, Marx, and Weber were grappling with a rapidly changing world in the nineteenth century—a time marked by the rise of industrial capitalism, urbanization, and the collapse of traditional social orders. Their theories not only addressed the challenges of their time but also laid the groundwork for the sociological frameworks we use today.

Durkheim’s emphasis on social facts—the norms, values, and structures that shape our behavior—provided the intellectual foundation for structural functionalism. His study of suicide, for instance, highlights how individual actions are deeply influenced by the social world. Marx’s critique of capitalism, with his focus on historical materialism and the base and superstructure, inspired conflict theory, emphasizing the role of economic power and inequality in shaping society. Meanwhile, Weber’s work on the Protestant ethic and his analysis of meaning and rationalization, though distinct, influenced both conflict theorists and symbolic interactionists in their examination of values, ideas, and social action.

Studying these thinkers helps us see how sociology evolved into the discipline we recognize today. But more importantly, their insights remain vital for understanding our current world. When we analyze how societal pressures affect mental health, Durkheim’s theories come into play. When we critique the widening economic inequalities of late capitalism, Marx’s ideas about power and exploitation are indispensable. And when we reflect on how modern work and consumerism shape our values, Weber’s exploration of the interplay between culture and economy offers critical insights.

As you read this chapter, consider how the ideas of Durkheim, Marx, and Weber connect to the theoretical perspectives you’ve already learned. These are not just historical concepts—they are tools to help you decode the complexities of today’s society and understand your own role within it.

Émile Durkheim and the Study of Suicide: Understanding Society Through Social Facts

Brief Biography

Émile Durkheim (1858-1917), a towering figure in the field of sociology, was born in 1858 in France into a family steeped in religious tradition. Descended from a long line of rabbis, Durkheim was expected to follow this religious path. However, he charted a different course, one that would lead him to become a pioneer in the study of society. Breaking away from his religious upbringing, Durkheim turned his intellectual curiosity toward understanding the structures and functions of society.

Durkheim’s academic journey led him to a significant milestone in 1896 when he was appointed the first full professor of Social Science at the University of Bordeaux. This appointment was not just a personal achievement for Durkheim but also a landmark event in French academic history. It marked the recognition of social science as a legitimate and important field of academic inquiry.

In 1898, Durkheim extended his influence on the academic world by creating L’Année Sociologique, a scholarly journal dedicated exclusively to the study of sociology. This journal became a crucial platform for disseminating sociological research and theories and played a pivotal role in establishing sociology as an independent academic discipline.

Durkheim’s life and career were deeply impacted by World War I. During the war, he served as the Secretary of the Committee for the Publication of Studies and Documents of War for France. This role immersed him in the analysis and documentation of the social and psychological impacts of war. Tragically, the war also brought personal sorrow to Durkheim when his son was killed in battle in 1915. This loss profoundly affected Durkheim, casting a shadow over his later years. The grief and stress from this personal tragedy are believed to have contributed to his declining health, leading to his death by stroke in 1917.

Theoretical Contributions: A Legacy of Sociological Foundations

Durkheim greatly influenced the field of sociology through several key publications. In The Division of Labor in Society (1893), he explored the transition from pre-modern to modern societies, introducing the concepts of mechanical and organic solidarity. This work examines how societal cohesion shifts from shared beliefs to interdependence driven by a complex division of labor. His Rules of Sociological Method (1895) established a framework for studying social facts—elements of social life that influence individual behavior. This book laid the groundwork for sociological research methodology, emphasizing empirical analysis.

Durkheim further delved into the role of religion in The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912), analyzing its impact on societal bonds and collective consciousness. Posthumously published, Education and Sociology (1922) highlighted the importance of education in socializing children and perpetuating societal norms and values. Through these works, Durkheim provided a deeper understanding of societal dynamics and the interplay between the individual and the collective while helping to establish sociology as a distinct and rigorous academic discipline.

Among these contributions, his 1897 book Suicide stands out as a landmark study that reshaped how sociologists view personal actions within broader social contexts.

What is a Social Fact?

Durkheim’s concept of social facts lies at the heart of his sociological approach. Social facts are elements of social life that exist independently of any single individual and exert a powerful influence on their behavior. These facts are external to the individual, meaning they are not created by a person’s individual thoughts or feelings but are instead products of the collective social environment. They include institutions (like the legal system), norms (such as social expectations about table manners), values (such as beliefs in democracy or equality), and even shared assumptions (like the sanctity of marriage).

To understand how these examples are social facts, let’s break some down:

- Religious Beliefs: In many societies, religious norms govern not only personal spirituality but also collective practices like holidays, rituals, and moral judgments. These norms are constructed through shared beliefs and practices passed down over generations. They shape individual identity and behavior, influencing everything from dietary habits to moral decision-making, regardless of whether someone actively adheres to a specific faith.

- Social Expectations (e.g., Table Manners): Something as seemingly trivial as table manners illustrates how social facts operate. Practices like saying “please” and “thank you” are learned through socialization, and violating these norms often results in disapproval or discomfort from others. These expectations were constructed socially—they vary across cultures and historical periods—and yet they profoundly influence how individuals behave in everyday interactions.

What makes social facts especially compelling is their dual nature: they are both external to the individual and social constructions. They exist because people collectively create, maintain, and reinforce them through shared practices, yet they take on a life of their own, exerting influence even over those who might reject or question them. For example, the concept of marriage as a lifelong partnership is a social construction—it varies across cultures and time—but it exists as an institution that deeply shapes individuals’ choices and expectations.

Durkheim argued that social facts must be studied empirically, as real phenomena, much like scientists study physical objects. This approach was groundbreaking because it established sociology as a discipline distinct from philosophy or psychology. Social facts are important because they reveal how individuals are shaped by forces beyond their personal experiences, providing insight into the collective dynamics of society.

Suicide as a Social Fact

Durkheim’s study of suicide serves as a powerful example of how personal actions are influenced by social facts. In his groundbreaking work Suicide, Durkheim asked whether this deeply personal act was simply an individual decision or a phenomenon shaped by broader societal forces. His conclusion was revolutionary: suicide is a social fact.

To support this claim, Durkheim analyzed extensive European suicide rate statistics and identified patterns that could not be explained solely by individual psychology. Instead, he linked variations in suicide rates to differences in social structures, demonstrating how external societal forces influence even the most intimate of decisions.

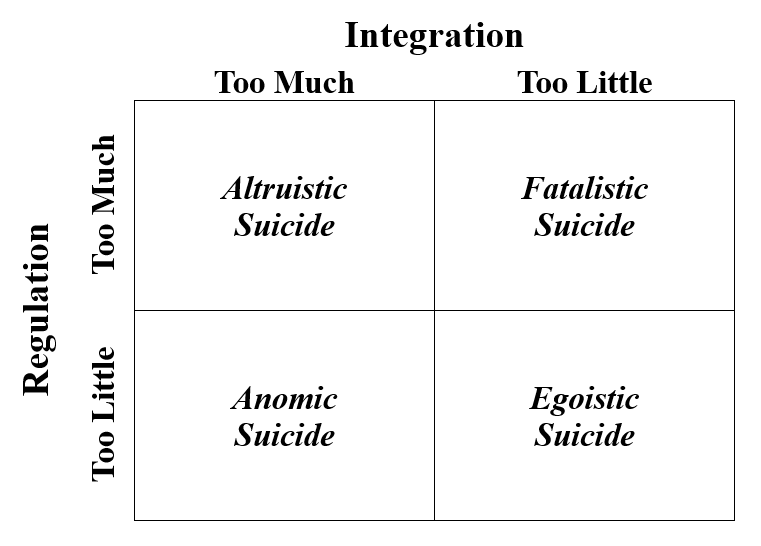

Durkheim identified four types of suicide, each corresponding to specific levels of social integration and regulation within society: altruistic suicide, egoistic suicide, anomic suicide, and fatalistic suicide.

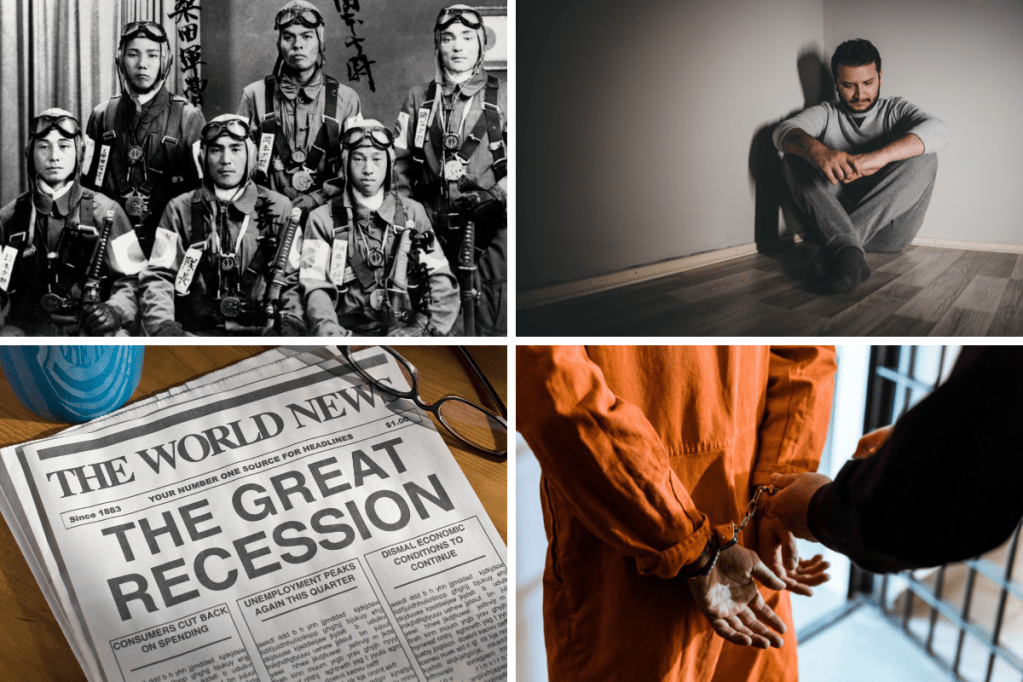

Altruistic suicide occurs in societies where social integration is so strong that individual identity is completely absorbed by the collective. In these settings, personal desires and needs become secondary to one’s duty to the group. Loyalty, honor, and devotion to a cause can become so deeply ingrained that individuals willingly sacrifice their lives for the perceived greater good. Durkheim pointed to collectivist cultures, where the well-being of the group takes precedence over individual survival, as places where this type of suicide is most common. A striking historical example comes from World War II, when Japanese kamikaze pilots carried out suicide missions as acts of patriotic duty. Their sacrifice was not seen as a loss but rather as a noble contribution to their country, reinforcing the idea that individual lives hold meaning only in relation to the group. In the modern world, similar patterns can be observed in cases where individuals commit acts of self-destruction for ideological or religious causes. The phenomenon of suicide bombers or self-immolation as a form of political protest raises important ethical and sociological questions about the balance between individual agency and collective belonging.

In contrast, egoistic suicide emerges in societies where social integration is weak, leaving individuals isolated and disconnected from meaningful relationships or shared values. When people lack strong ties to family, community, or institutions, they are more likely to experience a sense of purposelessness, leading to despair. Durkheim’s research revealed that unmarried individuals had higher suicide rates than those who were married, a pattern he attributed to the absence of the social bonds and responsibilities that marriage provides. Similarly, those who are elderly, marginalized, or lacking a support system are at greater risk of egoistic suicide. In contemporary society, the effects of loneliness and social isolation remain deeply relevant. The paradox of digital communication, where people are virtually connected but physically and emotionally distanced, has intensified feelings of alienation. The increasing prevalence of mental health struggles linked to isolation underscores Durkheim’s argument that social bonds are crucial for maintaining a sense of purpose and emotional stability.

While egoistic suicide results from too little integration, anomic suicide arises when rapid societal change disrupts established norms and expectations. Durkheim described anomie as a state of normlessness, where individuals lose their sense of direction due to sudden upheaval. This can occur during times of economic crisis, political instability, or personal loss—any moment when the usual structures of life are thrown into chaos. During the Great Depression, for instance, widespread unemployment and financial ruin left many people feeling lost and without a clear path forward, contributing to a surge in suicides. More recently, the 2008 financial crisis produced a similar pattern, as individuals facing sudden job loss and foreclosure struggled to find stability. Today, anomic suicide continues to be a pressing issue in societies experiencing rapid change. Technological disruptions in the workforce, for example, can lead to mass layoffs, leaving workers uncertain about their futures. Natural disasters, political revolutions, and even personal crises like divorce can also create the conditions for anomic suicide, demonstrating the ongoing relevance of Durkheim’s insights into the importance of stable social structures.

Unlike anomic suicide, which results from too little regulation, fatalistic suicide arises when social regulation is excessively rigid, trapping individuals in circumstances that feel unbearable. Although Durkheim spent less time on this type, it is nonetheless an important category. Fatalistic suicide occurs when individuals feel oppressed by extreme societal control, with no hope of change or escape. Prisoners subjected to harsh conditions, for instance, may experience overwhelming despair due to their loss of autonomy. Similarly, people living in authoritarian societies, where personal freedoms are severely restricted, may feel that their futures are predetermined and meaningless. Even outside of these extreme examples, fatalistic suicide remains relevant in contemporary discussions about mental health. Those experiencing workplace burnout, where excessive control and relentless expectations leave little room for autonomy, may struggle with feelings of hopelessness. Similarly, individuals in abusive relationships or trapped in oppressive cultural traditions may feel they have no agency over their own lives, illustrating how rigid social structures can erode personal well-being.

Why Does Suicide Matter as a Social Fact?

By demonstrating that suicide is influenced by external societal factors, Durkheim’s work challenged the prevailing view of suicide as purely an individual act. This insight has profound implications. It shows how individual behaviors are embedded within and shaped by the larger social world. Moreover, it emphasizes the importance of studying societal structures and collective forces to understand human actions.

Durkheim’s study remains a cornerstone of sociology because it highlights the power of social integration and regulation in maintaining societal stability—or, conversely, in contributing to social problems. His concept of social facts continues to guide sociologists in analyzing phenomena ranging from crime rates to mental health trends.

In studying suicide, Durkheim provided a model for understanding how sociology can illuminate the hidden connections between individual actions and the broader social forces that shape them. This approach not only underscores the scientific rigor of sociology but also its potential to address pressing social issues.

Karl Marx: Understanding History Through Class and Conflict

Brief Biography

Karl Marx (1818–1883) is renowned for his revolutionary ideas about economics, society, and politics, which continue to influence academic and political thought today. Although he never identified as a sociologist, his theories laid the groundwork for understanding how societies are shaped by class conflict and economic systems.

Born in Trier, Prussia (modern-day Germany), Marx came from a family of Jewish ancestry, with a lineage of rabbis. However, when he was seven, his father converted the family to Protestantism to avoid widespread discrimination against Jews. Marx began studying at the University of Bonn but was expelled after one semester due to his rebellious nature. He later joined the University of Berlin, where he became involved with the Young Hegelians, a group of thinkers who challenged traditional views on religion, politics, and philosophy. Their radical ideas greatly shaped Marx’s intellectual development.

Marx’s critical writings soon drew the attention of authorities. In 1843, he was exiled from Prussia for criticizing the government. He fled to Paris, where he met Friedrich Engels, his lifelong collaborator. Together, they developed many of the ideas that would form the foundation of socialism. Forced to leave Paris in 1845, Marx eventually settled in London with his family. Despite his affluent upbringing, Marx lived most of his life in poverty. Only four of his eight children survived to adulthood.

While in London, Marx devoted himself to extensive reading and writing. He was an active member of political movements, including the First International, an organization advocating for workers’ rights and socialism. His writings, including articles for the New York Daily Tribune, gained significant influence, reportedly even reaching figures like Abraham Lincoln.

Karl Marx died in 1883, still impoverished but intellectually influential. His theories about class struggle, capitalism, and historical change remain cornerstones of sociology, economics, and political thought, inspiring debates about inequality and justice to this day.

The Stages of History: History as Theory

Karl Marx, along with Friedrich Engels, introduced a revolutionary way of understanding history in The Communist Manifesto (1848), a text that continues to shape how we think about society today. Their theory, known as historical materialism, argues that the structure of society—its politics, culture, and institutions—is fundamentally tied to its economic foundation. At the heart of this foundation are the means of production (tools, labor, and resources used to create goods) and the mode of production, which refers to how these resources are organized and controlled. For Marx, the mode of production defines each stage of history—slavery, feudalism, capitalism, socialism, and communism.

This relationship between economics and society is captured in Marx’s concept of the economic base and superstructure. The economic base, consisting of the mode of production and labor relationships, forms the foundation of society. From this base emerges the superstructure: the institutions, laws, and cultural beliefs that uphold and reinforce the economic system. For instance, under capitalism, a base centered on private property and profit leads to laws that protect private ownership and cultural values that celebrate competition and individual success. Marx argued that understanding this relationship is essential to analyzing how societies function and why they change.

Each mode of production, however, contains internal conflicts and tensions—problems that arise from the relationships between those who own the means of production and those who do not. These tensions drive historical change as societies struggle with exploitation, inequality, and instability. For instance, feudalism relied on serf labor, but as trade and industry expanded, the rigid structures of feudal society gave way to capitalism. Similarly, Marx argued that capitalism, despite its innovation and growth, is inherently unstable due to its focus on profit, exploitation of workers, and recurring economic crises. These conflicts, he believed, would eventually lead to capitalism’s collapse, paving the way for socialism and, ultimately, communism.

By linking economic systems to social and cultural structures, Marx provides a framework for understanding history as a process shaped by material conditions and class struggles. This framework transforms history from a series of random events into a dynamic story of conflict and progress. In the sections that follow, we will explore each mode of production in detail to uncover how these ideas illuminate the evolution of societies and the forces driving historical change.

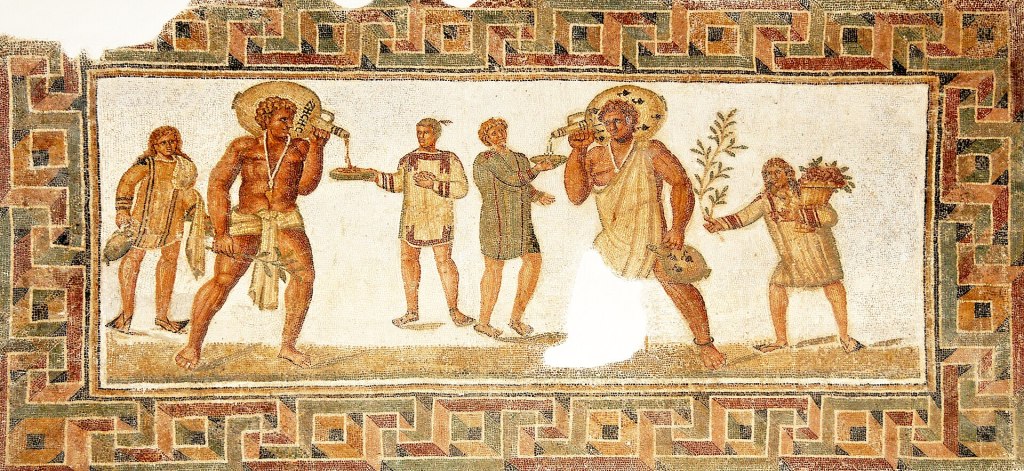

Slavery Mode of Production

The Slavery Mode of Production, as described by Karl Marx, was one of the earliest systems of economic organization, characterized by the division between masters (owners) and slaves (non-owners). Masters controlled wealth and resources, while slaves, treated as property, provided the labor that powered agriculture, construction, and other essential sectors of society. This system relied on forced human labor due to the lack of advanced technology, making enslaved people a primary source of economic and social value.

While slavery allowed masters to amass wealth and maintain power, it was inherently unstable. The relentless demand for more slaves to expand production created significant tensions. In ancient Greece, for example, Athens depended on a large enslaved population to sustain its democracy—a contradiction that exposed the system’s fragility. In Sparta, the Helots, an enslaved class that outnumbered Spartan citizens, required constant control, forcing Sparta to become a militarized society and weakening its long-term stability.

In the Roman Empire, slavery fueled vast agricultural estates (latifundia), displacing smaller citizen-run farms and contributing to urban poverty as displaced farmers migrated to cities. Rome’s reliance on slave labor also strained its military, as campaigns to capture new slaves overextended its forces and left the empire vulnerable to invasion.

The contradictions of the slavery system—economic inequality, social unrest, and reliance on forced labor—eventually made it unsustainable. As these tensions grew, they paved the way for the rise of feudalism, a new system of economic and social organization.

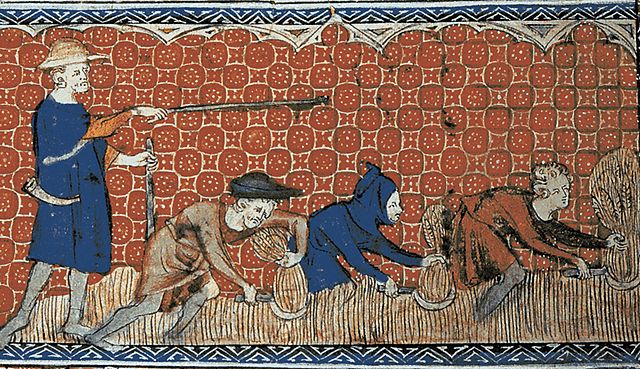

The Feudal Mode of Production

The Feudal Mode of Production emerged as the slavery system collapsed, offering a new way of organizing labor and resources. In feudal societies, wealth and power were tied to land ownership. Nobles, or landowners, controlled vast estates and provided protection to peasants, known as serfs, who worked the land. Unlike slaves, serfs were not considered property but were bound to the land and lacked the freedom to leave without permission. In return for their labor, serfs received small plots to farm for their survival.

The feudal mode of production was centered on agriculture, with land being the primary source of wealth. This system created a clear class division: the nobility, who owned the land and reaped its profits, and the serfs, who were economically dependent on the landowners. Serfs’ labor provided the food and resources that sustained the feudal economy, while nobles maintained their authority through military and political power.

However, feudalism was not without its contradictions. Events like the Black Death in the 14th century decimated Europe’s population, leading to severe labor shortages. With fewer workers available, surviving serfs gained leverage to demand better conditions, wages, and even the freedom to leave their lords’ estates. This shift weakened the nobility’s control over the economy.

Ongoing wars also destabilized feudal societies. Conflicts such as the Hundred Years’ War between England and France drained resources and forced nobles to rely on costly mercenary armies, which further strained the system. Additionally, the growth of trade and the rise of towns introduced new economic opportunities that undermined the rural, land-based economy of feudalism.

As these pressures mounted, the feudal system began to erode. Serfs sought independence, trade expanded, and centralized monarchies started to replace the fragmented power of feudal lords. These changes laid the groundwork for the next stage of history: capitalism.

The Capitalist Mode of Production

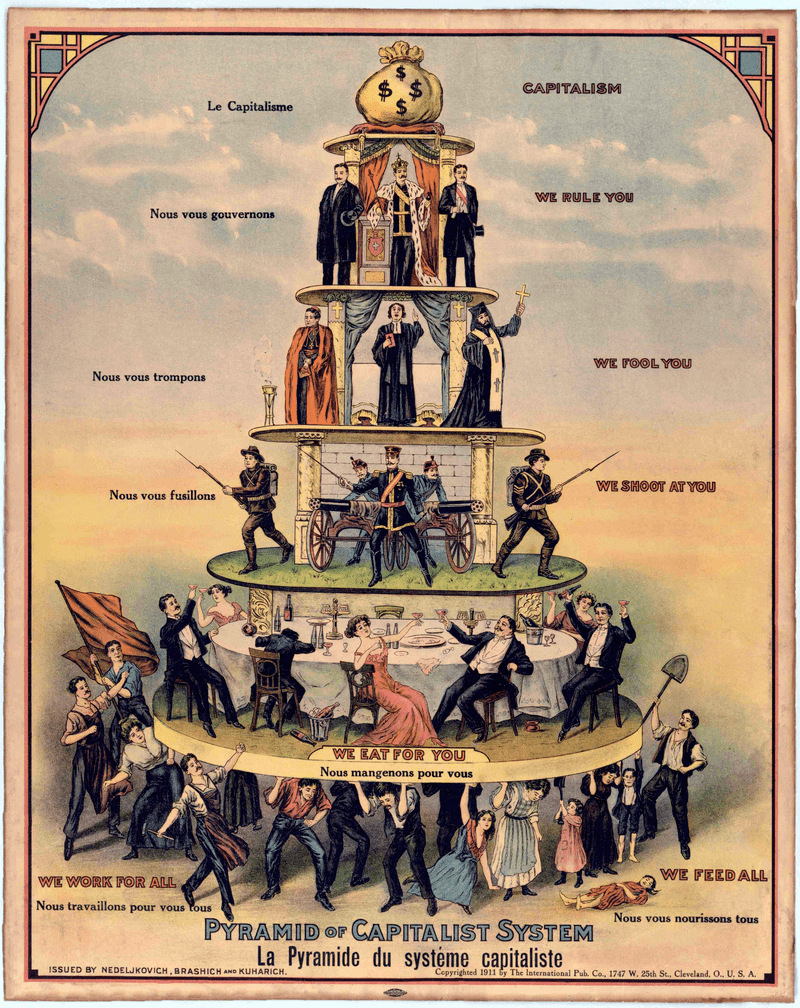

In Marx’s theory, the Capitalist Mode of Production is a system driven by the pursuit of profit and economic growth, defined by a sharp division between two main classes: the bourgeoisie (owners) and the proletariat (workers). The bourgeoisie controls the means of production—factories, tools, and resources—while the proletariat must sell their labor for wages. Unlike earlier systems, the primary source of wealth in capitalism is capital itself, which is reinvested to generate more profits.

The capitalist mode of production centers on industrial output and global markets. Factories produce goods that are sold for profit, and the system’s survival depends on constant expansion and reinvestment. Marx argued that this relentless pursuit of growth creates significant tension between the bourgeoisie, who benefit from accumulating wealth, and the proletariat, who face exploitation through low wages and harsh working conditions.

Capitalism’s drive for growth and profit also creates contradictions that threaten its stability. One major contradiction is the crisis of overproduction. When too many goods flood the market, prices drop, leading to economic downturns. An example is the 1920s farm crisis in the United States, when surplus wheat drove prices down and caused widespread financial struggles for farmers. Another contradiction lies in the call for government regulation to address capitalism’s harmful effects, such as worker exploitation or environmental damage. For instance, during the Industrial Revolution, poor working conditions led to the development of labor laws and safety regulations, which were often resisted by capitalists but became essential for social stability.

Marx also highlighted the role of technological advancement as a double-edged sword in capitalism. While new technologies increase efficiency and reduce costs, they can disrupt the balance between owners and workers. For example, the development of near-limitless energy sources, such as fusion power (still theoretical), could reduce production costs and challenge scarcity-based economic models, destabilizing the system’s reliance on class divisions. Marx argued that such contradictions would ultimately lead to capitalism’s collapse and pave the way for socialism.

Despite its dominance, capitalism, like the systems before it, is not permanent. Its internal tensions—economic inequality, periodic crises, and technological shifts—create the conditions for systemic change, setting the stage for the rise of socialism.

The Socialist Mode of Production

The Socialist Mode of Production, as envisioned by Marx, emerges from the contradictions and crises of capitalism. It represents a transitional phase where traditional class divisions—such as the gap between owners and workers—begin to dissolve. In socialism, the means of production, like factories and land, are collectively owned, and resources are distributed equitably to meet everyone’s needs. This shift significantly reduces, or even eliminates, scarcity, a major driver of class conflict in earlier stages.

A key feature of socialism is its extension of democracy into the economic sphere. Unlike capitalism, where economic power is concentrated in the hands of a few, socialism ensures that everyone has a voice in decisions about how resources are used and organizations are run. Marx imagined that advancements in technology and social organization would allow societies to meet basic needs and more for all people, removing the competition over resources that fuels inequality.

Under socialism, the role of government changes dramatically. Regulatory institutions that manage inequalities in capitalist societies, like those controlling wages or wealth distribution, become less necessary as class divisions fade. This reduction in the need for centralized governance prepares society for the next and final stage of history: communism.

The Communist Stage or “End of History”

Communism, the culmination of Marx’s vision, represents a classless and stateless society where human cooperation replaces exploitation and competition. In this stage, resources are abundant and freely available, eliminating the economic struggles that defined earlier systems. With no classes or scarcity, the historical conflicts that drove societal change come to an end, a concept Marx described as “the end of history.”

In a communist society, traditional government structures “wither away” because they are no longer needed to manage class relations or enforce economic hierarchies. Instead, people collectively manage resources and production to meet communal needs. Scarcity, which has long underpinned systems of inequality and conflict, is eradicated through technological advancements and collective ownership.

For Marx, communism is not just another step in history but the resolution of all previous contradictions. It is a transformative state where society operates in harmony, guided by cooperation and equality. In this final stage, the dynamics of history—class struggles, economic crises, and power imbalances—are replaced by stability and communal well-being.

In conclusion, Karl Marx’s theories on the progression of socio-economic stages from slavery to communism provide a comprehensive framework for understanding historical and societal development. His ideas, although formulated in the 19th century, continue to influence contemporary thought on economics, politics, and social structures. By analyzing the inherent contradictions within each stage, Marx offers insights into the dynamics of societal change and the potential for future transformations. His legacy, marked by his profound impact on political economy and revolutionary thought, endures in the ongoing discourse about class struggle, capitalism, and the quest for a more equitable society.

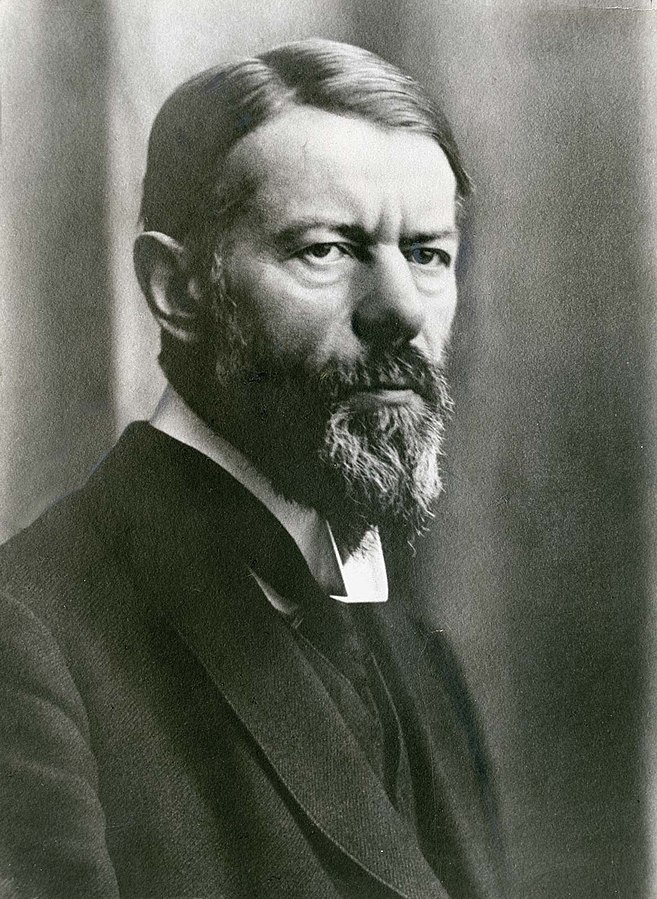

Max Weber: The Moral Foundations of Capitalism

Brief Biography

Max Weber (1864-1920), born in 1864 in Erfurt, Prussia (modern-day Germany), was the eldest of eight children in a well-off family marked by contrasting beliefs. His mother was deeply religious and a devout Calvinist, while his father was indifferent to religious matters, dedicating his time to politics. Their home served as a gathering place for politicians and academics.

Despite being a mediocre student, Weber was an enthusiastic reader, delving into philosophy, history, and classics. In 1882, he began studying law at Heidelberg University, later pursuing studies at various Prussian universities. In 1886, he obtained a law license, followed by a doctorate in 1889. Instead of practicing law, he pursued scholarly interests, collaborating with diverse scholars.

Weber’s academic pursuits were disrupted by military service and an active social life, including his engagement with Emmy Baumgarten, which ended due to her mental health issues. In 1893, he married his distant cousin, Marianne Schnitger, who played a pivotal role in his academic work while pursuing her own causes.

A quarrel with his father in 1897, followed by his father’s death, led to Weber’s struggle with mental health issues, causing him to withdraw from teaching in 1903. He eventually returned to teaching in 1918.

During World War I, Weber served in logistical roles due to his age and underwent a transformation from supporter to critic of German expansionism. Post-war, he became deeply involved in politics while continuing his academic pursuits. Weber passed away on June 14, 1920, due to pneumonia.

Max Weber stands as one of the most prolific classical sociologists, addressing topics such as religion, politics, power, and the economy through present observations and historical study. His wide-ranging contributions continue to shape sociological thought.

Weber’s Protestant Ethic and Spirit of Capitalism

Written in 1904 and 1905, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism is Max Weber’s most well-known work. It explores the relationship between the development of capitalism in Europe and the Reformation, particularly focusing on the rise of Protestantism, namely Calvinism. Contrary to Karl Marx’s view, which attributes the emergence of capitalism to material or economic circumstances, Weber posits that ideas, especially religious doctrines, were essential in shaping and spreading capitalism as Europe’s primary economic system.

Weber defines the ‘spirit of capitalism‘ as the continuous growth of capitalism through rational activities, notably the constant reinvestment of capital for growth. This includes the creation of a more rationalized capitalist system with developments like quantitative bookkeeping, a clear division of labor organized into a hierarchy, explicit rules, impersonality among workers, and labor structured around technology. Importantly, the ‘spirit of capitalism’ is not just the practice of these activities but a broader attitude that promotes them.

Weber argues that this attitude was deeply embedded in the growing Protestant movement, especially Calvinism, which he believed possessed values and attitudes distinct from other religions and Christian denominations. For instance, while the Old Testament God focused on a self-disciplined life and the New Testament God regarded worldly activity with indifference, Calvinism’s belief in predestination was markedly different.

Predestination is based on the belief that an all-knowing God has predetermined who will be saved or damned. Since individuals cannot influence their salvation, Calvinists believed that a small group was predestined for heaven. This led to the question of how to identify the chosen ones. Calvinists held that self-confidence in one’s status as chosen, evidenced by worldly success, was a marker. This success was fostered through the Protestant Work Ethic, whose characteristics include, but were not limited to:

- Hard Work and Diligence: Central to the Protestant Work Ethic is the value placed on hard work. Diligence in one’s labor is seen not just as a means to economic gain but as a moral virtue, reflecting a commitment to duty and responsibility.

- Asceticism and Abstinence from Physical Pleasure: This ethic promotes a lifestyle of moderation and self-denial, particularly in terms of abstaining from indulgences and pleasures. This restraint is viewed as a sign of moral strength and discipline.

- Thriftiness and Frugality: Emphasis is placed on saving and careful management of resources. Extravagance and wastefulness are frowned upon, with a focus instead on living modestly and within one’s means.

- Reinvestment and High Savings Rate: The Protestant Work Ethic encourages the reinvestment of profits back into one’s business or work, rather than spending on personal pleasures. This reinvestment is seen as a way to further one’s work and, by extension, fulfill one’s duty.

- Rational Approach to Work and Life: This ethic values a methodical and systematic approach to work. Planning, organization, and a rational assessment of tasks and goals are key components.

- Personal Calling and Vocationalism: Work is seen as a calling from God, with each individual having a specific role or vocation to fulfill. This spiritualizes work and integrates it with one’s religious and moral life.

These traits not only shaped individual Calvinists’ worldly successes but also fostered the disciplined, rational behaviors that supported the growth of capitalism. By linking economic activity to moral and religious purposes, the Protestant Work Ethic provided a cultural framework that made capitalism not just practical but virtuous. For Weber, this connection was key to understanding how capitalism emerged and spread in Europe, and the United States, driven by values that transformed work and profit into matters of spiritual significance.

From Faith to Profit: The Secularization of Capitalism and the Rise of the Hedonistic Ethic

While the Protestant Ethic was vital in creating and sustaining capitalism, Weber concludes that capitalism became secularized as it evolved into a global system. Over time, the religious motivations for work gave way to what Weber described as “the technical and economic conditions of machine production.” Practices like hard work, thrift, and reinvestment, once rooted in religious beliefs, became cultural norms driven by efficiency and profit rather than spiritual discipline. This transformation reflects a broader process Weber called disenchantment, where rational, calculated approaches replace moral or spiritual purposes. As capitalism grew, it shed its ethical foundations, leading some, like sociologist Daniel Bell (1919-2011), to argue in his 1976 book, The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism, that it ultimately gave rise to a contrasting cultural framework: the Hedonistic Ethic. This ethic, contrasting starkly with the Protestant Ethic, is characterized by the following characteristics:

- Pursuit of Pleasure and Leisure: Unlike the Protestant Ethic’s focus on hard work and asceticism, the Hedonistic Ethic prioritizes personal enjoyment and leisure activities. This shift reflects a societal move towards valuing immediate gratification and sensory experiences.

- Consumerism: Bell notes a transition from a culture of saving and reinvestment (key aspects of the Protestant Ethic) to one dominated by consumption and immediate gratification. In this context, success and happiness are often measured by the ability to consume and possess material goods.

- Throw-Away Culture: This ethic fosters a culture where products and experiences are disposable. Instead of the thrift and careful stewardship of resources promoted by the Protestant Ethic, the Hedonistic Ethic encourages a continuous cycle of consumption and discarding.

- Anti-Science or Professionalized Science: There’s a shift in the perception of science. Where the Protestant Ethic encouraged a fascination and exploration of God’s creation (which could include scientific endeavors), the Hedonistic Ethic either views science with skepticism or reduces it to a mere profession devoid of deeper ethical or philosophical implications.

In conclusion, Weber’s analysis of the Protestant Ethic and its role in the development of capitalism highlights the complex interplay between religious beliefs and economic practices. His work, juxtaposed with Bell’s later analysis, underscores the dynamic nature of societal values and their profound impact on economic systems. As capitalism evolved from a system rooted in religious ethics to one driven by hedonistic values, it reflects the changing priorities and cultural shifts within society, raising critical questions about the sustainability and future trajectory of capitalist economies.

Conclusion

The contributions of Émile Durkheim, Karl Marx, and Max Weber remain central to sociology, not only for their foundational role in shaping the discipline but for their ongoing relevance in understanding today’s world. Durkheim’s focus on social facts revealed how individual behavior is embedded in larger social structures, offering insights into phenomena like mental health and social integration. Marx’s theory of history illuminated the dynamics of class conflict and economic systems, inspiring critiques of inequality and capitalism’s contradictions. Weber’s analysis of the Protestant ethic underscored the cultural and ideological forces driving economic behavior, raising questions about how values evolve alongside economic systems.

Together, these thinkers demonstrate the power of sociological inquiry to connect individual experiences, structural forces, and cultural values. Their work invites us to think critically about how society functions and changes—and to apply these insights to address the challenges of the present. Whether exploring the role of social norms, the persistence of inequality, or the shifting priorities of a consumer-driven world, the legacies of Durkheim, Marx, and Weber provide essential tools for understanding and shaping the societies we live in today.

Key Terms

Altruistic Suicide (Durkheim): A type of suicide that occurs when individuals are overly integrated into a group, prioritizing the collective to the point of sacrificing themselves.

- Example: Japanese kamikaze pilots during World War II viewed their self-sacrifice as an honorable act for their country, driven by loyalty and group identity.

Anomic Suicide (Durkheim): A type of suicide resulting from a breakdown of social norms and regulations, leaving individuals feeling lost or disconnected.

- Example: Widespread unemployment and financial instability during the Great Depression caused some individuals to lose their sense of purpose, leading to despair.

Bourgeoisie (Marx): The class that owns and controls the means of production, such as factories, land, and capital, in capitalist societies.

- Example: Industrialists during the Industrial Revolution accumulated significant wealth and power by owning factories and employing workers.

Calvinism (Weber): A Protestant denomination emphasizing predestination and a disciplined lifestyle, which Weber argued influenced the development of capitalism.

- Example: Calvinists believed that hard work, thrift, and success were signs of being among God’s chosen, shaping their economic behaviors.

Capitalist Mode of Production (Marx): An economic system where production is driven by private ownership of resources and profit motives, characterized by the division between owners and workers.

- Example: Factories producing goods for sale on a global market, with owners reinvesting profits to expand production, exemplify capitalism.

Communism (Marx): The final stage of societal development, where resources are collectively owned, class divisions are eliminated, and scarcity no longer exists.

- Example: In a communist society, all individuals would have equal access to resources, and economic struggles over wealth and power would be resolved.

Economic Base (Marx): The foundation of society, consisting of the means of production and the relationships that define how goods and services are produced.

- Example: In feudal societies, the economic base centered on agriculture, with land ownership defining class relationships.

Egoistic Suicide (Durkheim): A type of suicide that occurs when individuals lack strong social ties, leading to feelings of isolation and purposelessness.

- Example: Higher suicide rates among unmarried individuals reflect weaker social bonds and fewer communal responsibilities.

End of History (Marx): The theoretical culmination of societal development in communism, where class conflicts and economic struggles are resolved, halting the need for further historical change driven by conflict.

- Example: In a communist society, collective ownership and the elimination of scarcity would remove the historical basis for social and economic divisions.

Fatalistic Suicide (Durkheim): A type of suicide that occurs when individuals face excessive regulation and feel trapped by oppressive societal conditions.

- Example: Prisoners in harsh, restrictive environments may feel they have no autonomy or hope for change, leading to fatalistic suicide.

Feudal Mode of Production (Marx): An economic system based on land ownership, where nobles controlled resources, and serfs provided labor in exchange for protection.

- Example: Medieval serfs worked the land for their lords, receiving small plots to farm for their subsistence in return for their labor.

Hedonistic Ethic (Bell, building on Weber): A set of cultural values that prioritize pleasure, leisure, and consumption over hard work and discipline.

- Example: Modern consumer culture emphasizes instant gratification and material wealth, often at the expense of savings or long-term goals.

Historical Materialism (Marx): The theory that the organization of economic production drives historical change, with each stage of society marked by its unique economic conflicts and structures.

- Example: The transition from feudalism to capitalism was driven by the growth of trade, technological advancements, and conflicts over land use.

Masters (Marx): The class in the slavery mode of production that owned enslaved individuals and controlled their labor to produce wealth.

- Example: Roman masters relied on slaves to work large agricultural estates, building their wealth and social status.

Means of Production (Marx): The tools, resources, and facilities used to produce goods and services in an economy.

- Example: Factories, machinery, and raw materials are the means of production in industrial societies.

Mode of Production (Marx): The system of economic organization that defines how goods and services are produced and distributed, shaping societal relationships and structures.

- Example: Feudalism, capitalism, and socialism are distinct modes of production, each characterized by specific class dynamics.

Nobles (Marx): The landowning elite in feudal societies who controlled resources and held political and military power.

- Example: Feudal lords governed estates, enforcing laws and providing protection in exchange for labor from serfs.

Overproduction Crisis (Marx): A contradiction of capitalism where goods are produced in excess of what the market can absorb, leading to economic downturns.

- Example: The agricultural surplus in the 1920s caused wheat prices to collapse, creating financial hardship for farmers.

Predestination (Weber): The Calvinist belief that God has already determined who will be saved or damned, shaping attitudes toward work and success as signs of divine favor.

- Example: Calvinists viewed material success as evidence of being among the “elect,” motivating their disciplined economic behaviors.

Proletariat (Marx): The working class in a capitalist society, which sells its labor to the bourgeoisie in exchange for wages.

- Example: Factory workers during the Industrial Revolution labored under exploitative conditions, forming the foundation of Marx’s critique of capitalism.

Protestant Work Ethic (Weber): A set of values emphasizing hard work, discipline, and frugality, which Weber argued contributed to the development of capitalism.

- Example: Calvinists reinvested profits into their businesses rather than indulging in personal luxuries, fostering economic growth.

Serfs (Marx): Agricultural laborers in feudal societies who were tied to the land and provided labor to nobles in exchange for protection.

- Example: Serfs worked fields and paid rents to their lords while relying on their protection from external threats.

Slavery Mode of Production (Marx): An economic system where enslaved individuals were treated as property and forced to work for their masters.

- Example: The Roman Empire relied on enslaved labor for agriculture and infrastructure, creating vast disparities in wealth and power.

Social Fact (Durkheim): Elements of social life, such as norms, institutions, and values, that exist outside individuals and shape their behavior.

- Example: The legal system functions as a social fact, influencing individual actions through collectively enforced rules.

Socialist Mode of Production (Marx): A transitional stage where resources are collectively owned, and class distinctions begin to dissolve, reducing societal inequalities.

- Example: In socialism, workers collectively own factories and land, distributing profits more equitably among all members of society.

Spirit of Capitalism (Weber): A set of attitudes promoting rational economic behavior, reinvestment of profits, and the pursuit of continuous growth.

- Example: Entrepreneurs who prioritize efficiency and reinvest profits into expanding their businesses exemplify the spirit of capitalism.

Superstructure (Marx): The cultural, political, and institutional framework built on the economic base, reflecting and supporting the mode of production.

- Example: In capitalist societies, laws protecting private property serve to reinforce the dominance of the bourgeoisie over the proletariat.

Reflection Questions

- How did Emile Durkheim’s idea of social facts help establish sociology as a science, and what does it mean to study social forces as things?

- What does Karl Marx mean when he says that history is a history of class struggle, and how does this idea help us understand conflict in society today?

- How did Max Weber’s concept of verstehen change the way sociologists study social action, and why did he believe values and meaning matter alongside facts?

- What are the key differences between the theories of Emile Durkheim, Karl Marx, and Max Weber, and how does each explain the structure and change of society in a distinct way?