Table of Contents

- Learning Objectives

- Introduction

- The Scientific Method

- The Sociologist’s Toolbox

- Ethics in Sociological Research: Navigating Responsibility

- Conclusion: Asking Questions, Building Understanding

- Key Concepts

- Reflection Questions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, students will be able to:

- Explain the scientific method and its significance in sociological research, including how it distinguishes evidence-based findings from opinion or anecdote.

- Identify the historical development of the scientific method, recognizing contributions from figures such as Aristotle, Ibn al-Haytham, Galileo, Bacon, and Descartes, and their relevance to contemporary sociological inquiry.

- Describe and apply the steps of the scientific method in the context of a sociological study, including question formulation, literature review, hypothesis development, data collection, analysis, and reporting.

- Differentiate between major sociological research methods—quantitative, qualitative, experimental, and historical—and explain the strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of each.

- Evaluate the benefits and limitations of survey research, including challenges related to sampling, question design, response bias, and depth of insight.

- Analyze the critiques of surveys and statistics offered by sociologists such as C. Wright Mills and Joel Best, including concerns about superficiality, misrepresentation, and the need for statistical literacy.

- Summarize the key features and uses of qualitative research methods, including participant observation, ethnography, and case studies, and assess their value in capturing rich, contextual understandings of social life.

- Discuss the purposes and ethical concerns of experiments in sociology, including historical examples like the Robbers Cave Experiment and their contributions to theory and policy.

- Explain how historical methods are used in sociology to trace the roots of contemporary issues and illustrate long-term social change, including reference to Wallerstein’s world-systems theory.

- Recognize the central role of ethics in sociological research, including the purpose of IRBs, ASA guidelines, and lessons from historical violations such as the Tuskegee Study and Milgram Experiment.

- Articulate the importance of ethical, evidence-based research in a world shaped by misinformation and polarized discourse, and describe sociology’s unique contributions to building an informed and equitable society.

Introduction

Why do some neighborhoods thrive while others face persistent challenges? How do new technologies reshape the ways we connect with one another? What factors drive social movements, and why do some succeed while others falter? These are the kinds of questions that sociologists grapple with—questions that demand answers grounded in evidence, not conjecture. To tackle such complexities, sociologists rely on a range of carefully crafted research methods that transform curiosity into structured inquiry.

In today’s polarized world, the need for such disciplined approaches has never been greater. Public debates, from economic inequality to climate change, often rest on untested assumptions, with opinions masquerading as facts. This is particularly evident in the heated critiques of higher education. Critics accuse universities of fostering echo chambers or being disconnected from societal needs, often painting academic disciplines like sociology as “out of touch.” However, much of this criticism itself relies on anecdote and opinion rather than rigorous research.

Sociology, as a field, provides a counterweight to these tendencies by emphasizing systematic methods, transparency, and ethical responsibility. Whether through surveys that capture large-scale trends, qualitative studies that illuminate personal stories, or experiments that test cause-and-effect relationships, sociology equips us with tools to see the world more clearly and act on insights responsibly.

In this module, we’ll explore the methods sociologists use to answer society’s most pressing questions. From the scientific method to the ethics that safeguard participants, this journey through sociological research will show not only how we seek answers but also why it matters to get those answers right.

The Scientific Method

What is the Scientific Method, and Why Is It Important?

The scientific method is a systematic process used to explore questions, test ideas, and uncover truths about the world around us. At its core, it is a disciplined approach to inquiry that relies on observation, experimentation, and analysis to ensure conclusions are based on evidence rather than speculation or opinion. This distinguishes findings from the scientific method from other forms of information—whether someone’s personal belief, a viral claim from social media, or even a well-crafted argument in the news. While these sources might feel convincing, they lack the rigor and reliability that come from carefully testing hypotheses, gathering data, and critically evaluating results.

The importance of the scientific method lies in its ability to transcend individual bias, offering a structured way to investigate complex problems and uncover patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed. It provides the tools to validate discoveries through testing and replication, ensuring that what we accept as knowledge is trustworthy and broadly applicable. For sociologists, the scientific method is essential for analyzing the complexities of human behavior and societal structures in a systematic and transparent way.

However, the scientific method didn’t emerge fully formed. Its development was a long, iterative process shaped by the contributions of brilliant thinkers over centuries. Each of these pioneers added a unique element, refining the process into the framework we use today. Let’s explore this journey.

The Thinkers Who Shaped the Scientific Method

The scientific method has a rich history, shaped by the contributions of key thinkers over centuries. Each of these figures added critical elements that refined the systematic approach we now use to study both the natural and social worlds.

The origins of systematic inquiry can be traced to Aristotle (384–322 BCE), who emphasized observation and categorization of the natural world. While his reliance on personal observation limited his work, Aristotle’s commitment to understanding the world through logic and evidence laid the groundwork for future methods.

Centuries later, during the Islamic Golden Age, Ibn al-Haytham (965–1040 CE) revolutionized inquiry by introducing controlled experimentation. His work in optics demonstrated the importance of testing theories under structured conditions and advocating for skepticism until evidence could confirm assumptions. This emphasis on empirical evidence became a cornerstone of modern science.

The experimental approach gained further momentum with Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), who is often regarded as the “father of modern science.” Galileo combined observation, experimentation, and mathematical analysis to test hypotheses systematically. His work on planetary motion and falling objects illustrated how precise measurements could challenge and refine existing knowledge.

The theoretical framework of the scientific method was formalized by Francis Bacon (1561–1626). Bacon argued for the importance of inductive reasoning, where researchers begin with specific observations and build toward general theories. This approach underscored the need to collect evidence before drawing conclusions, forming the foundation of modern empirical research.

Finally, René Descartes (1596–1650) introduced a complementary focus on deduction and logical reasoning. His method emphasized breaking problems into smaller parts to analyze them systematically, ensuring clarity and rigor in the pursuit of knowledge. Together with Bacon, Descartes provided a structured methodology that continues to guide scientific inquiry.

A Collaborative Inheritance: The Scientific Method in Sociology

The scientific method is not the creation of any single thinker but the product of a collaborative effort that spans centuries. The foundations laid by Aristotle and Ibn al-Haytham evolved through the innovations of Bacon, Galileo, and Descartes, culminating in a framework that transcends individual bias and ensures reliable pathways to discovery.

As sociology emerged in the 19th century, its pioneers adopted this method to establish the discipline as a science. For Émile Durkheim (1858-1917), the scientific method provided a way to analyze seemingly personal behaviors, such as suicide, through the lens of social forces like religion and community. By systematically studying data across societies, Durkheim revealed patterns that transformed the understanding of individual actions within a broader social context.

Max Weber (1864-1920) expanded this approach, emphasizing the importance of interpreting the meanings individuals attach to their actions. His work on religion and bureaucracy showed how cultural values and organizational structures influence behavior and societal development, blending empirical analysis with interpretive depth.

Sociology has continued to build on the scientific method, tailoring it to address the complexities of human behavior. By combining rigorous data collection with contextual interpretation, sociology not only observes the world but also seeks to understand it, uncovering insights that enrich our understanding of society and its structures.

Defining the Scientific Method

So, what exactly is the scientific method, and how does It apply to sociological research? The scientific method is more than just a checklist of steps—it’s a dynamic process that helps researchers turn curiosity into systematic inquiry. For sociologists, this method provides a structured way to explore the complexities of human behavior and social systems. While it has its roots in natural sciences, sociology adapts the scientific method to study phenomena like inequality, culture, and social change. But how does this process actually unfold?

At its core, the scientific method in sociology is a structured process of inquiry. It begins with a question about social phenomena and unfolds step by step to ensure conclusions are well-supported by evidence. Let’s examine how this process works, step by step, by considering an example of a sociologist studying how social media affects in-person interactions.

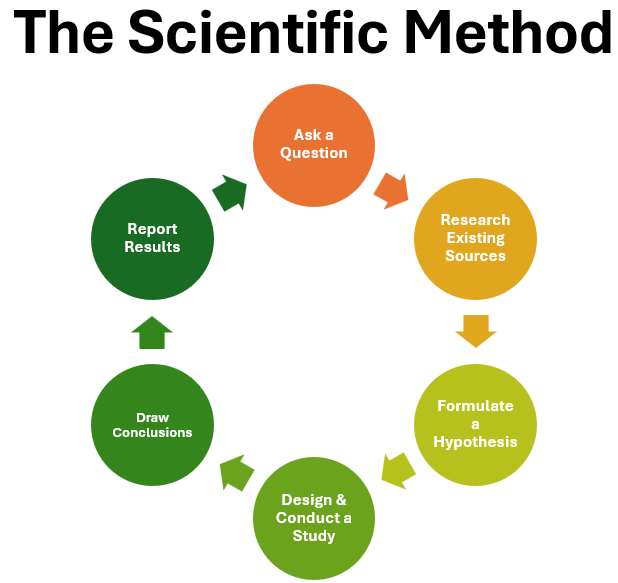

The steps of the scientific method include the following:

- Ask a Question: Every research project begins with a question. For sociologists, this question often arises from observations of society or gaps in existing knowledge. In our example, the sociologist notices that people often spend time scrolling through social media even during face-to-face gatherings. This sparks the question: “Does heavy social media use impact face-to-face social interactions?” This question is clear, focused, and researchable, setting the foundation for the study.

- Research Existing Sources: Before diving into original research, sociologists review what’s already known about the topic. This involves examining academic studies, theories, and data to understand the current state of knowledge. For the social media example, the sociologist reviews studies on screen time, communication norms, and the psychological effects of social media. They discover a gap: while much has been written about teenagers and social media, fewer studies focus on adults. This review helps refine the study’s focus and ensures it builds on, rather than duplicates, previous work.

- Formulate a Hypothesis: Armed with insights from the literature, the sociologist formulates a hypothesis—a tentative statement that predicts an outcome or explains a phenomenon. For this study, the hypothesis might be: “Adults who spend more than two hours a day on social media will report fewer in-person social interactions compared to those who use it less frequently.” This hypothesis is specific, testable, and directly tied to the research question.

- Design and Conduct a Study: This step is where planning meets action. Sociologists select a research method that fits their question and hypothesis. For the social media study, the sociologist designs a survey to measure participants’ social media usage and the frequency of their in-person social interactions, such as meeting friends, attending events, or spending time with family. They also gather demographic data to see whether factors like age or occupation influence the results. The study then recruits a number of participants from diverse backgrounds, ensuring a mix of heavy social media users and non-users. The sociologist administers the survey online, collects the data, and ensures ethical research practices, including informed consent and confidentiality.

- Draw Conclusions: Once the data is gathered, the sociologist analyzes it to determine whether the findings support the hypothesis. They discover a clear trend: participants who report heavy social media use—more than two hours daily—also report fewer in-person interactions. However, they uncover an unexpected nuance: the impact of social media use on in-person interactions varies by age, with younger adults more affected than older adults. This analysis not only supports the hypothesis but also provides additional insights that deepen understanding of the topic.

- Report Results: The final step is sharing the findings. Sociologists publish their results in academic journals, present them at conferences, or write reports to inform policy or practice. In this case, the sociologist might publish their study in a journal, detailing the methods, findings, and implications. For example, they suggest that heavy social media use might substitute for in-person interactions among younger adults, while for older adults, it complements existing social routines. By sharing results, the sociologist contributes to a broader dialogue within the academic community, inviting critique, replication, and further research.

Each step of the scientific method—asking, researching, hypothesizing, designing, analyzing, and reporting—plays a crucial role in transforming a question into meaningful insights. Together, these steps create a framework that brings clarity and rigor to the study of society, empowering sociologists to uncover patterns and connections that might otherwise go unnoticed. The scientific method isn’t just about finding answers—it’s about building a systematic, reliable path to understanding the complexities of our social world.

The Sociologist’s Toolbox

As sociologists embark on their journey into research, they carry with them a versatile toolbox filled with methods, each uniquely crafted to help them unravel the complexities of the social world. These methods are more than techniques; they are lenses through which sociologists can examine human behavior, relationships, and structures from different perspectives.

Broadly, the sociologist’s toolbox can be divided into three primary categories: quantitative methods, qualitative methods, and historical methods, with experiments serving as a versatile tool that cuts across these categories. Each of these approaches is suited to particular types of questions, offering unique insights into the intricate workings of society.

Quantitative methods are the workhorses of large-scale sociology, focusing on collecting numerical data that can be statistically analyzed. These methods allow sociologists to zoom out and capture broad patterns, trends, and correlations across large populations. Think of quantitative methods as the telescopes of sociology, providing a clear but distanced view of the big picture. Through surveys, statistical analysis, and experiments, quantitative tools make it possible to identify societal shifts and compare behaviors across groups and time periods.

In contrast, qualitative methods invite researchers to zoom in, delving into the details and meanings that define individual and group experiences. By using tools like participant observation, ethnography, and case studies, sociologists can uncover the rich, nuanced stories that numbers alone cannot tell. These methods are akin to magnifying glasses, helping sociologists closely examine the subtleties of human behavior, culture, and social interaction.

Historical methods add another dimension to the sociologist’s arsenal, enabling researchers to look back in time to understand the roots of present-day social phenomena. By analyzing historical records, archives, and artifacts, sociologists can trace the evolution of social systems, uncovering how past events shape contemporary dynamics. Historical methods serve as time machines, providing a broader context for understanding change and continuity in society.

Finally, experiments offer a powerful way to test hypotheses by isolating specific variables. Often associated with the natural sciences, experiments allow sociologists to examine cause-and-effect relationships in controlled or real-world settings. Whether testing theories in a laboratory or observing behaviors in the field, experiments provide a rigorous framework for exploring human behavior and social dynamics.

By integrating these methods, sociologists gain a comprehensive set of tools to address the complexities of the social world. Each method offers distinct strengths and perspectives, and together, they enable sociologists to approach questions with depth, rigor, and flexibility, ensuring a well-rounded understanding of society’s many facets.

The Quantitative Toolbox: The Survey

Surveys are one of the most essential tools in a sociologist’s quantitative toolbox. At their core, surveys are structured questionnaires designed to gather information from a group of people. They can target entire populations—like everyone at a university—or focus on strategically chosen samples that represent a larger group. By turning human experiences and opinions into data, surveys offer sociologists a way to quantify the complexities of society and uncover patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Imagine walking onto a bustling college campus. Students are sprawled across lawns, hurrying to class, or chatting in dining halls. Now picture a university administrator eager to understand how these students feel about their campus experience. Are they satisfied with the library? Do they feel supported when it comes to mental health? What could be improved? To answer these questions systematically, the university might conduct a survey.

A survey like this might include a variety of questions tailored to gather actionable insights:

- On a scale of 1-5, how would you rate the quality of the campus library facilities?

- Do you feel the university adequately addresses student mental health needs? (Yes/No)

- What improvements would you like to see in the campus dining services?

- How often do you participate in extracurricular activities? (Daily, Weekly, Monthly, Never)

When the students respond, their answers are no longer just individual opinions; they become part of a larger dataset. For example, suppose the survey finds that 60% of students believe the university doesn’t adequately address mental health needs. This number isn’t just a statistic—it’s a call to action, revealing an area of concern that might otherwise have gone unnoticed.

Similarly, if the average rating for library facilities is 3.5 out of 5, the university might see this as an opportunity to enhance library services. Perhaps most students report participating in extracurricular activities weekly, suggesting that student organizations are thriving. These insights, distilled from the survey data, help administrators understand the needs of their community and make informed decisions about where to allocate resources.

Surveys are more than just questionnaires—they are tools that bring clarity to the often-messy realities of human behavior and social structures. By organizing opinions, behaviors, and experiences into quantifiable data, surveys offer sociologists and other researchers a way to measure the pulse of society, one question at a time.

The Benefits of Surveys

But why are surveys so widely used in sociology? Let’s take a closer look at their benefits by imagining another example: you’re curious about the eating habits of teenagers at your school. To find answers, you design a survey asking questions like “How often do you eat fast food?” and “Do you think your diet is healthy?” As you start analyzing responses, the benefits of surveys become clear.

First, surveys have wide coverage. By distributing your questions to a diverse group of students, you can gather perspectives from people with different habits, lifestyles, and backgrounds. Instead of relying on conversations with a few friends, you now have input from a large group that gives you a fuller picture of eating habits in your school.

Next, surveys benefit from standardized questions. Everyone answers the same set of questions, ensuring consistency in the data you collect. If most students report eating fast food frequently, you can confidently identify a trend. Standardization also makes it easier to compare responses across different groups, like students in different grades or those involved in sports versus those who aren’t.

Surveys also provide quantifiable data, transforming opinions and behaviors into numbers you can analyze. Let’s say your survey reveals that 40% of students eat fast food more than three times a week, while only 20% consider their diet healthy. These numbers offer a clear and objective way to measure eating habits, making it easier to spot patterns and draw meaningful conclusions.

Another key benefit is their simplicity and accessibility. Unlike more complex research methods, surveys are straightforward to create and distribute. Once you’ve collected responses, tools like spreadsheets or statistical software can help you analyze the data. Imagine presenting your findings in a class project with colorful graphs showing how often students eat fast food or pie charts illustrating perceptions of healthy eating. Surveys make it easy to share insights in a way that’s both visually appealing and easy to understand.

Finally, surveys are invaluable for informing decisions. If your data shows that most students eat fast food because the cafeteria offers limited healthy options, you now have evidence to support change. School administrators might use your findings to introduce more nutritious meals, directly improving the environment for your peers.

Surveys, then, act like a magnifying glass, zooming in on the details of human behavior while offering a structured way to analyze and share what you’ve discovered. Whether you’re a student conducting a small-scale study or a sociologist investigating nationwide trends, surveys provide a methodical and accessible way to convert people’s experiences into actionable insights. It’s no wonder they’re considered a cornerstone tool in sociology.

The Challenges of Surveys

While surveys are powerful tools that allow sociologists to uncover patterns and trends, they are not without their limitations. Like any tool, they must be used carefully, with an understanding of their potential shortcomings. Let’s revisit the example of surveying eating habits in your school to explore some of these challenges in detail.

Surface-Level Insights

Imagine your survey asks, “How often do you eat fast food?” and you find that a large percentage of students eat it frequently. While this data highlights an important trend, it doesn’t tell you why. Are students choosing fast food because it’s convenient, affordable, or simply their favorite option? Or are they eating it because healthier choices aren’t available? Surveys often provide a broad overview of a phenomenon but may fail to capture the deeper reasons behind it. Without follow-up questions or complementary methods, such as interviews or focus groups, important context may be lost.

Sample Representation

Now imagine you distribute your survey during your own lunch period. What if the students in your lunch period are particularly fond of fast food compared to other periods? Your results might then reflect the preferences of a specific group rather than the entire student body. This is an issue of sample representation: ensuring that the group of people surveyed accurately reflects the larger population you’re trying to understand. If the sample is skewed, the conclusions you draw may not apply to the wider group, leading to misleading results.

Response Bias

When answering surveys, people don’t always tell the full truth. Let’s say your survey asks, “Do you think your diet is healthy?” Some students might feel pressured to say “yes” because it feels like the ‘right’ answer, even if they know it isn’t true. This is called response bias, and it can distort your results. People may also overestimate positive behaviors (like exercising) or downplay negative ones (like skipping meals), which can create a gap between what respondents report and what they actually do.

Question Comprehension

The way survey questions are worded can also pose challenges. For example, if your survey asks, “How frequently do you consume non-home-prepared meals?” some students might not realize this includes fast food. Others might find the phrasing confusing and skip the question altogether. Clear, simple language is essential to ensure respondents understand what you’re asking and provide accurate answers. If questions are unclear, the data you collect may not align with what you intended to measure.

Limited Response Options

Surveys often rely on predetermined answers, like checkboxes or multiple-choice questions, which can restrict the range of responses. Suppose your survey asks, “How often do you eat fast food?” with options like “once a week,” “twice a week,” and “every day.” What about students who eat fast food less than once a week? Without an option for them, their experiences go unrecorded, leaving gaps in your data. Limited response options can flatten the diversity of experiences, making it harder to capture the full complexity of the behavior you’re studying.

C. Wright Mills and His Critique of Surveys

Sociologist C. Wright Mills (1916-1962), in his influential book The Sociological Imagination, raised a compelling critique of surveys and the overreliance on statistical analysis. Mills argued that while surveys often reveal what is happening, they rarely explain why it’s happening. According to Mills, surveys run the risk of reducing complex social realities to oversimplified numbers, stripping away the rich, contextual meanings behind human behavior.

Mills cautioned against a “fetishism of the method,” where researchers become so focused on collecting data and calculating statistics that they lose sight of the larger social structures and historical forces shaping the patterns they observe. For instance, in our fast-food survey example, Mills might critique the survey for failing to address broader systemic issues, such as the role of advertising, economic inequality, or food deserts in shaping eating habits.

For Mills, the real value of sociology lies in connecting individual choices to larger social forces. Surveys may show us that students eat fast food frequently, but they don’t explain how corporate marketing strategies, family income, or cultural norms influence those choices. Mills challenged sociologists to use their “sociological imagination” to bridge the gap between personal experiences and societal structures, moving beyond surface-level data to uncover deeper truths.

Moving Forward: Joel Best and How to Address the Challenges of Surveys

While Mills highlighted the limitations of surveys, sociologist Joel Best (born 1946) offers practical advice on how to navigate these challenges. In his book Damned Lies and Statistics, Best provides tools for using surveys and statistical analysis more effectively, emphasizing the importance of skepticism and critical thinking.

Best begins by acknowledging the contradictions in how society views statistics, stating:

“We suspect that statistics may be wrong, that people who use statistics may be “lying”—trying to manipulate us by using numbers to somehow distort the truth. Yet, at the same time, we need statistics; we depend upon them to summarize and clarify the nature of our complex society.”

Joel Best, Damned Lies and Statistics

Rather than dismissing surveys or statistics outright, Best argues that we should approach them thoughtfully, recognizing that statistics are not independent truths but human creations. As Best explains, “people have to create them…and the process of creation always involves choices that affect the resulting number and therefore affect what we understand after the figures summarize and simplify the problem.”

For example, in the fast-food survey, the choices researchers make—how they word questions, define response categories, and select participants—all influence the results. If these choices are poorly made, the survey might produce misleading conclusions.

Best encourages sociologists to develop “statistical literacy,” asking critical questions like:

- Who created this survey, and what was their goal?

- How were the questions phrased, and could they have influenced the responses?

- Does the sample accurately represent the population being studied?

Incorporating Best’s perspective into survey research helps sociologists balance respect for the power of quantitative methods with a healthy skepticism. Surveys remain one of sociology’s most powerful tools, but their results require thoughtful interpretation to avoid misrepresentation. As Best reminds us, statistics should illuminate social phenomena, not obscure them.

The Power and Limits of Surveys

Surveys are like magnifying glasses: they provide valuable insights into human behavior but often leave deeper complexities unexplored. Mills challenges us to connect the individual choices revealed in surveys to larger social forces, while Best equips us with tools to critically evaluate and improve survey design and interpretation.

By combining these perspectives, sociologists can move beyond the limitations of surveys, using them not just to collect numbers but to uncover meaningful insights about the social world. In the next section, we’ll explore specific strategies for designing effective surveys and integrating them with other methods to better capture the complexities of society.

The Qualitative Toolbox: Exploring the Depths of Human Society

In sociology, qualitative research methods are akin to indispensable tools in a well-equipped toolbox, each uniquely designed to uncover the layered complexities of human society. These methods—participant observation, ethnography, and case studies—go beyond the surface-level data of quantitative research. They allow sociologists to step into the lives of individuals and communities, weaving narratives rich with insights into human behavior, relationships, and societal structures.

Where quantitative methods often answer the “what” of social trends, qualitative methods delve into the “why” and “how.” They reveal the personal stories, emotions, and cultural norms that shape human interactions, offering a vibrant and detailed portrait of our social world. To better understand how sociologists use these tools, let’s explore three key qualitative methods: participant observation, ethnography, and case studies.

Participant Observation: Seeing the World Through Their Eyes

Imagine you want to understand how new technologies affect family life. Numbers and surveys can show trends, like the average time people spend on their phones, but they can’t fully capture the lived experience of families navigating this digital age. This is where participant observation comes in.

Participant observation involves the researcher immersing themselves in a community or group, observing from the perspective of an insider. For instance, Barbara Ehrenreich (1941-2022), in her book Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, adopted this method to explore the lives of low-wage workers. Over three months, she worked minimum-wage jobs and lived as her subjects did, experiencing firsthand the physical and emotional toll of economic hardship. Her approach revealed systemic barriers to upward mobility and provided a vivid account of the challenges faced by working-class Americans—nuances that would have been invisible through surveys alone.

This method’s strength lies in its ability to uncover these kinds of subtleties that might be invisible in survey results or statistical charts. By immersing themselves in their subjects’ lives, researchers like Ehrenreich witness social phenomena as they unfold, offering a richer and more personal understanding of human behavior.

Ethnography: A Panoramic View of Culture

While participant observation focuses on specific groups or contexts, ethnography takes a broader, more immersive approach. It involves studying an entire community to understand their culture, traditions, and daily lives in context.

For example, Jennifer Sherman used ethnography in her book Those Who Work, Those Who Don’t: Poverty, Morality, and Family in Rural America. Over a year of living in a financially depressed Northern California town, Sherman combined participant observation with in-depth interviews to understand the social dynamics and moral judgments surrounding poverty. She attended local events, volunteered, and engaged deeply with residents, uncovering how economic decline reshaped social relationships and moral frameworks. Her work illuminated how communities navigate the divide between the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor, providing a textured understanding of the impacts of economic hardship on social life.

Ethnography provides a panoramic view of social life, revealing how individual experiences connect to broader cultural and economic contexts. It is a method that celebrates depth over breadth, offering insights into the intricate interplay between people and their environments.

Case Studies: Deep Dives Into the Specific

Sometimes, understanding a broader phenomenon requires focusing on a single case. This is where case studies excel. They allow researchers to examine a specific event, situation, or individual in great depth, uncovering details that can illuminate larger social dynamics.

A compelling example is Alice Goffman’s (born 1982) On the Run: Fugitive Life in an American City. Goffman spent six years immersed in a heavily policed Philadelphia neighborhood, closely observing a group of young men known as the 6th Street Boys. Her work explored how constant police surveillance and criminalization affected their lives, families, and community dynamics. By observing their daily routines and struggles, Goffman captured the pervasive stress and disruption caused by their need to evade law enforcement. However, her work also highlighted the challenges of maintaining objectivity, as her deep involvement with her subjects raised ethical and methodological questions.

Case studies like Goffman’s provide a detailed portrait of social life, offering insights into how specific events or dynamics unfold. Although their focus on individual cases can limit their generalizability, the depth of understanding they offer often resonates far beyond their immediate context.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Qualitative Methods

Qualitative methods—like participant observation, ethnography, and case studies—are some of sociology’s most powerful tools for understanding the complexities of human behavior and culture. They allow researchers to step into the worlds of their subjects, capturing the stories, emotions, and interactions that bring social phenomena to life. However, like any research method, they come with both advantages and challenges that sociologists must carefully navigate.

The Strengths: Depth and Detail

One of the greatest strengths of qualitative methods is their ability to produce rich, nuanced observations that reveal the lived experiences behind social phenomena. Immersive methods like participant observation and ethnography allow researchers to step into the daily lives of their subjects, uncovering the intricate ways broader social forces manifest in personal relationships and routines.

For example, Ehrenreich’s deeply immersive exploration of low-wage workers in Nickel and Dimed reveals the physical and emotional toll of trying to make ends meet on minimum wage. Her approach captures systemic barriers like the scarcity of affordable housing or the exploitation of labor, creating a vivid narrative that raw statistics could never provide. Similarly, Sherman’s ethnographic study of rural poverty in Those Who Work, Those Who Don’t highlights how economic decline reshapes moral frameworks and social relationships, providing a profound look at how communities define the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor.

These works illustrate the strength of qualitative methods in revealing the personal dimensions of social issues, from economic inequality to cultural judgment. Whether it’s navigating systemic barriers or grappling with shifting moral landscapes, the stories uncovered by qualitative research illuminate the human side of sociology, offering insights that can guide policy and deepen our understanding of social dynamics.

The Limitations: Scale and Objectivity

Despite their depth, qualitative methods face significant limitations. One of the primary challenges is their narrow scope. Since these methods often focus on smaller groups or specific communities, their findings may not apply to broader populations. For instance, Goffman’s detailed account in On the Run provides an unparalleled view of life under constant police surveillance, yet its applicability to other communities remains debated. The tension between depth and generalizability is an ongoing challenge in qualitative research.

Bias is another potential issue. The immersive nature of qualitative methods often blurs the line between observer and participant, making it difficult for researchers to maintain complete objectivity. Goffman’s close relationships with her subjects raised ethical and methodological questions about how deep involvement can influence findings, highlighting the fine line between empathy and detachment that qualitative researchers must walk.

Finally, while qualitative methods excel at uncovering the “why” and “how” of social phenomena, they struggle to establish causality. Ehrenreich’s compelling narrative of low-wage workers reveals the systemic challenges they face but stops short of identifying specific policies or practices that create these conditions. Similarly, Sherman’s ethnographic insights offer a vivid picture of rural poverty but cannot definitively explain the broader structural factors driving economic decline.

Balancing the Trade-Offs

Qualitative methods, while rich in detail, are most effective when used with a clear understanding of their limitations. They offer depth at the expense of breadth, emphasizing the lived experiences of individuals and small groups over sweeping generalizations. Sociologists often combine qualitative methods with quantitative approaches to strike a balance—using numbers to identify trends and qualitative tools to uncover the stories behind those trends.

Despite their challenges, qualitative methods remain invaluable for understanding the human side of sociology. The works of Ehrenreich, Sherman, and Goffman illustrate the profound insights these methods can provide, as well as the complexities researchers must navigate to maintain ethical and methodological integrity. Qualitative research reminds us that behind every statistic is a story, and behind every trend is a web of interactions, meanings, and emotions waiting to be explored.

Expanding the Sociologist’s Toolbox: Experiments and Historical Methods

Sociology is a discipline that thrives on diverse methods, each offering a unique lens to examine human behavior and social structures. While surveys, interviews, and ethnographies allow sociologists to observe and analyze the present, other methods enable them to test specific hypotheses or delve into the past to uncover the roots of contemporary issues. Two such approaches—experiments and historical methods—play vital roles in the sociological toolbox.

Experiments: Testing Theories in Action

Experiments are a powerful tool for testing sociological theories under controlled conditions. They allow researchers to manipulate an independent variable—such as exposure to persuasive messaging—and measure its effect on a dependent variable, like changes in attitudes or behavior. For instance, a lab-based experiment might examine how certain types of advertisements influence consumer preferences, isolating variables to reveal clear cause-and-effect relationships. Alternatively, field-based experiments take research into real-world settings, where the complexity of everyday life provides greater ecological validity, even if controlling variables becomes more difficult.

One of the most famous sociological experiments is the Robbers Cave Experiment (1954) led, where researchers led by Muzafer Sherif (1906-1988) observed the dynamics of intergroup conflict and cooperation among boys at a summer camp. Through staged competition, they demonstrated how rivalry emerges from competition for scarce resources. In the final phase, the introduction of shared goals—such as fixing a water supply—reduced hostility and fostered collaboration. This experiment highlighted the potential for group conflict resolution but also raised ethical concerns, as participants were unaware of the true nature of the study.

While experiments excel at clarifying causal relationships, they have limitations. Lab experiments may oversimplify social phenomena, reducing the rich complexity of human interactions to isolated variables. Ethical considerations are also paramount; researchers must carefully balance the need for insight with the protection of participants. Despite these challenges, experiments remain invaluable for exploring how specific factors influence human behavior and testing theories that inform broader sociological understanding.

Historical Methods: Understanding the Past to Illuminate the Present

Historical methods involve the systematic study of past events, records, and artifacts to understand how societies and social structures evolve. By examining archives, letters, newspapers, and government records, sociologists can uncover the origins of contemporary social issues and trace the long-term processes that shape them. This method is particularly useful for exploring questions about change and continuity, such as how industrialization transformed family life or how global power dynamics shift over centuries.

An influential example of historical methods is Immanuel Wallerstein’s (1930-2019) The Modern World-System Volume I. In this seminal work, Wallerstein used historical data to analyze the rise of capitalism as a global economic system. Tracing the development of the world economy from the 16th century onward, Wallerstein argued that the modern global order is shaped by a core-periphery structure, where wealthier nations dominate trade, production, and resources while poorer nations are relegated to subordinate roles. His historical approach illuminated how economic and political power are deeply intertwined and how historical processes continue to shape inequalities in the modern world.

While historical methods offer unparalleled depth and contextual understanding, they come with challenges. Historical records can be incomplete or biased, requiring researchers to critically assess their sources. Additionally, interpreting the past through a modern lens risks projecting contemporary assumptions onto historical contexts. Despite these limitations, historical methods remain essential for connecting present-day phenomena to their roots, offering a richer understanding of how societies develop and adapt.

Ethics in Sociological Research: Navigating Responsibility

Sociological research holds immense power to reveal the complexities of human behavior and societal structures. With this power, however, comes the profound responsibility to ensure that research respects the dignity and rights of participants. History has shown us the devastating consequences of neglecting this responsibility, making ethical considerations a cornerstone of the discipline.

To guide researchers in this crucial aspect of their work, the American Sociological Association (ASA) has established a comprehensive code of ethics. These principles help sociologists navigate complex questions about privacy, consent, and harm, ensuring that their research upholds the highest standards of integrity. Additionally, institutional safeguards, such as Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at colleges and universities evaluate proposed studies to ensure compliance with ethical standards and protect participants from harm. Together, these frameworks aim to strike a balance between the pursuit of knowledge and the protection of those involved in research.

But why are these safeguards so vital? The answer lies in the lessons of history—examples of unethical research that caused irreparable harm and exposed the dangers of neglecting ethical principles.

Historical Lessons: Ethics Violated

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–1972)

For forty years, the U.S. Public Health Service conducted a study on 600 African American men in Macon County, Alabama, under the guise of providing free healthcare. Of these men, 399 had syphilis, while the remaining 201 were part of a control group. The participants were told they were being treated for “bad blood,” a local term for various ailments, but in reality, they were being observed to study the untreated progression of syphilis.

Even after penicillin was established as an effective treatment in the 1940s, the participants were deliberately denied access to the drug. The consequences were devastating: many men suffered severe health complications, passed the disease to their wives, and transmitted congenital syphilis to their children. The study ended only after a whistleblower exposed its unethical practices to the media in 1972, sparking national outrage. In response, stricter ethical regulations were implemented, including the requirement for informed consent and the establishment of IRBs to oversee research involving human subjects.

The Guatemala Syphilis Experiment (1946–1948)

While less well-known, the Guatemala Syphilis Experiment represents one of the most egregious violations of research ethics in history. Conducted by American scientists, this study involved infecting over 1,300 Guatemalan prisoners, soldiers, and mental patients with syphilis, gonorrhea, and chancroid. Participants often had no knowledge of their involvement, let alone the risks they faced.

The methods were horrifying: some participants were deliberately infected through wounds or spinal injections, while others were exposed via infected sex workers paid to engage with them. The stated aim was to determine whether penicillin could prevent infections post-exposure, but the lack of transparency, consent, and humane treatment made the study a glaring example of unethical research. Decades later, President Obama formally apologized to Guatemala, acknowledging the profound harm caused by the experiment and reinforcing the importance of rigorous ethical standards in research.

The Milgram Experiment (1961)

In a laboratory at Yale University, psychologist Stanley Milgram (1933-1984) set out to understand obedience to authority figures, especially in the wake of atrocities committed during World War II. Participants were told they were part of a study on learning and memory, where they would administer electric shocks to a “learner” (an actor) whenever an incorrect answer was given.

As the experiment progressed, the voltage of the shocks increased, and the actors simulated increasingly intense pain. Participants, believing the shocks were real, often expressed distress but continued to administer them under the researcher’s encouragement. Though no physical harm occurred, the emotional toll on participants was significant—many left the study visibly shaken, believing they had caused genuine suffering. Milgram’s failure to properly debrief participants compounded the ethical concerns, highlighting the importance of transparency and care in research design.

While the experiment demonstrated how authority could compel individuals to act against their moral beliefs, it also underscored the need for ethical safeguards to protect participants from emotional distress.

Learning From the Past

These historical cases serve as stark reminders of the harm that can occur when ethical principles are ignored. They emphasize the need for sociologists to adhere to established guidelines, such as those outlined by the ASA and enforced by IRBs, to ensure their work respects participants’ rights and well-being. By learning from the past, sociologists can conduct research that not only advances our understanding of society but also upholds the values of respect, dignity, and integrity that are foundational to the discipline.

Ethics are not just rules—they are the heart of responsible sociological inquiry, reminding us that the pursuit of knowledge must never come at the expense of humanity.

Conclusion: Asking Questions, Building Understanding

The heart of sociology lies in its ability to ask meaningful questions and answer them with precision, insight, and integrity. By employing the scientific method, sociologists craft a structured approach to inquiry, testing ideas and uncovering patterns that reveal how societies function and change. Through quantitative methods, we can identify broad trends, while qualitative approaches uncover the personal narratives and intricate social dynamics behind the data. Experiments and historical methods offer additional layers of understanding, helping us test theories and connect the present to the past.

But as this module has shown, research is not just about the methods—it’s about the responsibility to use them ethically. History reminds us of the devastating consequences when ethical standards are ignored, and it inspires us to uphold principles of respect, transparency, and fairness in every step of the research process.

In an era marked by misinformation and division, sociology’s commitment to rigorous, ethical inquiry offers a path forward. By combining curiosity with careful methodology, sociologists contribute to a deeper understanding of society—an understanding that challenges assumptions, elevates discourse, and empowers us to build a more informed and equitable world. Whether we’re investigating social problems, testing new ideas, or simply seeking to understand the people around us, the tools and principles of sociological research remain as vital as the questions they help us answer.

Key Concepts

Case Study: A detailed investigation of a single individual, event, or group to uncover broader social patterns or implications.

- Example: A sociologist studying the closure of a major factory in a small town might examine how the event impacts community relationships, mental health, and local businesses, providing insights into broader trends in economic decline and social adaptation.

Ethnography: A qualitative research method involving the immersive study of a community to understand their culture, practices, and social dynamics.

- Example: A sociologist might spend a year living in a remote fishing village to study how environmental changes affect their traditions, survival strategies, and sense of identity.

Experiments: A research method that tests hypotheses under controlled conditions by manipulating an independent variable and observing its effect on a dependent variable.

- Example: A sociologist might test whether exposure to different types of media messages influences voting behaviors by exposing groups to varied content and measuring their reactions.

Guatemala Syphilis Experiment: An unethical American-run study (1946–1948) where prisoners, soldiers, and mental patients were deliberately infected with venereal diseases to test penicillin’s efficacy.

- Example: This study involved infecting participants without informed consent, often through invasive procedures, leading to significant harm and a formal apology decades later.

Historical Methods: A research approach that examines past records, events, and artifacts to understand how societies evolve over time.

- Example: Immanuel Wallerstein’s The Modern World-System used historical analysis to trace the development of capitalism and global inequalities from the 16th century onward.

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs): Committees that evaluate proposed research projects to ensure ethical compliance and protect participants from harm.

- Example: An IRB would review a sociological study involving interviews with trauma survivors to ensure their rights and well-being are safeguarded throughout the research process.

Milgram Experiment: An experiment (1961) by psychologist Stanley Milgram testing obedience to authority, where participants were instructed to administer electric shocks to a “learner.”

- Example: Though the shocks were fake, many participants believed they were real, leading to emotional distress and highlighting ethical concerns about informed consent and debriefing.

Participant Observation: A qualitative method where researchers immerse themselves in a group or community to observe and understand social behaviors from an insider’s perspective.

- Example: Barbara Ehrenreich adopted participant observation in Nickel and Dimed by working minimum-wage jobs to understand the challenges of low-wage workers.

Qualitative Methods: Research methods that explore deeper meanings and personal experiences through interviews, participant observation, and case studies.

- Example: Jennifer Sherman’s ethnographic study in Those Who Work, Those Who Don’t examined the moral judgments surrounding poverty in a rural community.

Quantitative Methods: Research methods focusing on numerical data collection and statistical analysis to uncover trends and patterns.

- Example: Asociologist might use surveys to measure how often college students participate in extracurricular activities and correlate this with academic success.

Robbers Cave Experiment: A 1954 field experiment studying intergroup conflict and cooperation among boys at a summer camp.

- Example: The study demonstrated that rivalry arose from competition but was reduced when the groups worked together on shared goals, highlighting theories of group dynamics and conflict resolution.

Scientific Method: A systematic process of inquiry involving observation, hypothesis formation, experimentation, and analysis to ensure conclusions are evidence-based.

- Example: Émile Durkheim used the scientific method in his study of suicide to uncover how social forces like community and religion influence individual behavior.

Survey: A quantitative research method involving structured questionnaires to collect data from a population or sample group.

- Example: A university might use a survey to measure student satisfaction by asking questions about campus facilities, mental health resources, and participation in extracurricular activities, turning responses into numerical data for analysis.

Tuskegee Syphilis Study: A 40-year-long unethical study (1932–1972) observing the effects of untreated syphilis in African American men without providing them treatment.

- Example: Participants were misled to believe they were receiving care, even after penicillin became available, causing widespread harm and prompting stricter research ethics guidelines.

Reflection Questions

- What are the strengths and limitations of survey research in sociology, and how can the wording or structure of questions shape the results?

- What makes participant observation and ethnography valuable for understanding social life, and what ethical or practical challenges do these methods create for researchers in the field?

- How does the choice of research method—such as interviews, experiments, or secondary data analysis—affect the type of knowledge a sociologist can produce?

- What ethical dilemmas do sociologists face when studying human behavior, and how do principles like informed consent and harm prevention shape the research process?