Table of Contents

- Learning Objectives

- Introduction

- What are Social Groups?

- Robert Putnam & the Importance of Social Capital

- Max Weber’s Three Types of Authority

- Group Size & Dynamics: Georg Simmel’s Dyads, Triads, and Larger Groups

- Rationalization & its Discontents

- Conclusion

- Key Terms

- Reflective Questions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, students will be able to:

- Define and distinguish between types of social groups, including primary groups, secondary groups, reference groups, aggregates, and categories, and explain their roles in shaping social interaction and identity.

- Describe the expressive and instrumental functions of primary and secondary groups and apply these concepts to everyday social settings such as families, workplaces, and classrooms.

- Analyze the concept of social capital using Robert Putnam’s distinction between bonding and bridging capital, and evaluate how different types of connections influence group solidarity, trust, and access to resources.

- Explain Max Weber’s three types of authority—traditional, charismatic, and rational-legal—and assess how each type shapes group cohesion, legitimacy, and leadership stability.

- Examine Georg Simmel’s theories of group size, including the dynamics of dyads, triads, and larger groups, and interpret how group size influences interaction, intimacy, stability, and power relations.

- Apply the concept of rationalization to modern organizations, including Weber’s theory of bureaucracy and Ritzer’s theory of McDonaldization, and identify how principles such as efficiency, predictability, calculability, and control shape group operations.

- Critically evaluate the unintended consequences of rationalized systems, including the phenomenon Ritzer calls the “irrationality of rationality,” using examples from education, healthcare, and service industries.

- Interpret Zygmunt Bauman’s sociological analysis of the Holocaust as a case of rationalized violence, and reflect on how bureaucratic systems, when detached from ethical considerations, can enable dehumanization and atrocity.

- Synthesize key theories and examples to understand how social groups structure individual behavior and broader social organization, balancing rational systems with the need for ethical and humane group life.

Introduction

How do we navigate the countless relationships and organizations that shape our lives? Whether we’re bonding with close friends, collaborating in a workplace team, or looking up to role models, the social groups we engage with profoundly influence who we are and how we see the world. These groups range from the intimate and emotional to the formal and goal-oriented, each serving a unique role in the fabric of society. But not every gathering of people forms a social group—so what defines a group, and why does it matter?

In this exploration of social groups, we’ll uncover the distinctions between primary and secondary groups, delve into the influence of reference groups, and examine categories and aggregates that fall outside the definition of true groups. Drawing on the work of sociologists like Robert Putnam, Max Weber, and Georg Simmel, we’ll also explore the role of social capital, authority, and group dynamics in shaping how individuals connect and collaborate. Finally, we’ll consider the broader implications of rationalized systems, from the predictability of fast-food chains to the chilling efficiency of historical events like the Holocaust.

Through these perspectives, we’ll gain a deeper understanding of how social groups structure our interactions, reflect societal values, and influence the choices we make every day.

What are Social Groups?

In sociology, understanding social groups is crucial because these groups shape individual identities, behaviors, and interactions, reflecting the diverse ways people organize and navigate society. Social groups are more than just gatherings; they involve regular interaction, shared expectations, and a common purpose. This idea helps explain how people move through social spaces with others, from close family circles to larger, more goal-driven organizations. By exploring the types and dynamics of social groups, we can appreciate the roles people play within them and how these roles influence broader society.

A primary group, for instance, consists of people who share deep emotional bonds and frequent interaction, such as family members or close friends. These relationships are fundamental, shaping values, beliefs, and a sense of belonging that strongly influences one’s personal identity. Primary groups also serve an expressive function, as they meet emotional needs, offering support and comfort in times of stress or joy. For example, when a student faces personal challenges, they often turn to family or close friends for emotional support, relying on these deep, personal connections.

In contrast, secondary groups are larger and more impersonal, typically centered around specific goals or tasks rather than emotional ties. These groups, like workplace teams or classroom cohorts, are more formal and short-term, prioritizing task completion over personal connection. Secondary groups serve an instrumental function, as their primary focus is on achieving specific objectives or completing tasks. For instance, in a group project or work team, members collaborate to reach a common goal, such as completing an assignment or meeting a deadline, with less emphasis on personal relationships.

In addition to primary and secondary groups, reference groups serve as standards people look to for self-evaluation. Reference groups can shape individual behavior, social norms, and personal goals by providing models to emulate or adapt. A professional organization, for example, might be a reference group for a college student who aspires to adopt certain values and behaviors as they move into a similar career.

Not all social gatherings, however, form actual groups. Aggregates, for example, are collections of people who happen to be in the same place at the same time, like people waiting in line at a coffee shop. They share physical proximity but lack a shared identity or interaction that would connect them as a social group. Similarly, categories refer to people who share specific characteristics, such as gender, age, or occupation, but who may not directly interact or share a sense of belonging to one another.

Together, these types of social groups illustrate the different ways individuals connect within society. By examining primary and secondary groups, as well as reference groups, aggregates, and categories, sociologists can analyze social behavior and relationships, exploring how individuals experience and contribute to the complex structure of society. Understanding these social dynamics provides insight into the bonds that tie individuals to each other and to society as a whole.

Robert Putnam & the Importance of Social Capital

Social capital, a concept explored in-depth by the polotical theorist, Robert Putnam in Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (2000), is essential to understanding social groups and their dynamics. Social capital refers to the networks of relationships and social connections that provide individuals with access to resources, support, and a sense of belonging. Within the study of social groups, social capital plays a crucial role in shaping group interactions, cohesion, and overall effectiveness. Putnam’s work reveals how social capital—through both bonding and bridging ties—helps maintain social groups’ structure, support, and influence within society. He argues that the decline of social capital in the United States has weakened community connections and social engagement, affecting everything from civic participation to collective trust.

Bonding social capital represents the “strong ties” found within primary social groups, such as family, close friends, or small, close-knit communities. These bonds foster deep emotional connections, loyalty, and mutual support, reinforcing the cohesiveness of groups. In the context of social group dynamics, bonding capital allows members to rely on each other for personal support, shared values, and a strong sense of identity. However, because bonding capital is typically exclusive, it can lead to insularity or even mistrust toward out-groups. For example, in a small rural town, residents may prioritize helping one another, strengthening community ties, but this can also lead to resistance to outsiders or new ideas. Bonding social capital thus enhances solidarity within groups but may limit broader social integration.

In contrast, bridging social capital involves the “weak ties” that connect individuals across different groups, fostering inclusivity and access to new resources. Bridging capital is often found in secondary groups, like professional networks or larger community organizations, and is essential for linking people from diverse backgrounds. This type of social capital expands individuals’ access to information, opportunities, and support outside their immediate circle, enhancing group adaptability and resourcefulness. For instance, professionals who participate in cross-industry networking events gain insights that help their organizations grow. However, bridging ties tend to be less personal, which may make them less emotionally supportive. Bridging social capital plays a key role in connecting distinct social groups, facilitating information flow, and broadening perspectives, all of which support dynamic group interactions.

Putnam’s examination of social capital highlights how bonding and bridging capital are both essential for a balanced and dynamic social landscape. Bonding capital strengthens group cohesion and identity within social groups, while bridging capital fosters openness and inclusivity across different groups. In the study of social groups, this distinction helps us understand how different types of ties contribute to group solidarity, resilience, and adaptability. Putnam’s concern about declining social capital underscores the importance of these group dynamics, suggesting that a loss in either type of capital can diminish community trust, social support, and engagement. By analyzing social capital within the framework of group dynamics, we can better appreciate the intricate relationships that sustain both small and large social groups in society.

Max Weber’s Three Types of Authority

Authority is central to studying social groups because it explains how power is organized, maintained, and exercised within different social contexts. Authority shapes group dynamics by influencing members’ behavior, expectations, and compliance with group norms or leaders. Without authority, groups would lack cohesion and direction, as authority provides the structure needed to organize group efforts, maintain order, and achieve shared goals. In sociology, authority is essential to understanding not only why individuals follow certain leaders or rules but also how groups develop loyalty, identity, and purpose.

Max Weber’s (1864-1920) exploration of authority in his essay The Three Types of Legitimate Rule and later in Economy and Society provides a foundational framework for analyzing authority in social groups. Weber identified three types of legitimate authority—traditional, charismatic, and rational-legal—each with unique characteristics that influence the structure and stability of groups. These ideal types help explain the various ways leaders maintain legitimacy and control, affecting group cohesion and adaptability in different contexts.

Traditional authority is based on long-standing customs or cultural practices that people in a group or society have come to accept over time. Leaders hold power not because of any formal qualifications or elections, but because tradition says they should. For example, in a monarchy, a king or queen holds authority because they inherit it through a family line, and people respect this position because it’s deeply embedded in their cultural or historical background. This kind of authority creates a strong sense of continuity and stability within groups, as it connects people to shared traditions and history. However, traditional authority can sometimes be resistant to change, as it’s focused on preserving established ways rather than adapting to new ideas.

Rational-legal authority is based on formal rules, laws, and established procedures that everyone in a group or organization agrees to follow. Leaders hold power because they’re appointed or elected according to these rules, not because of personal traits or family background. For example, a mayor, judge, or police officer has authority because they hold a position defined by legal structures, and people respect them because they operate within a rule-based system. Rational-legal authority creates consistency and fairness, as it relies on rules that apply equally to everyone, rather than on individual relationships. While this type of authority helps large organizations run smoothly, it can sometimes feel impersonal, as decisions are often made according to rules rather than individual needs.

Charismatic authority is a type of authority where the power of the leader rests on their extraordinary personal qualities, which inspire deep loyalty and devotion from followers. This form of authority is grounded in the belief in the leader’s vision, personality, or mission, rather than in tradition or formal rules. Examples include revolutionary figures like Martin Luther King Jr. or religious leaders such as Gandhi, whose personal charisma united followers around a cause.

However, charismatic authority is inherently unstable and often fleeting since it depends heavily on the leader’s continued influence. Weber noted that once a charismatic leader loses appeal, dies, or is removed, the authority can disintegrate unless it undergoes routinization, which is a transformation into a more enduring form of authority. This process can take one of two forms:

- Traditional Authority: The leader’s teachings or legacy may become embedded within cultural or religious practices, transforming their influence into traditional authority. This can be seen when followers establish rituals or traditions based on the leader’s values, ensuring continuity after their departure.

- Rational-Legal Authority: Alternatively, the leader’s ideals may be codified into formal rules or structures, creating a rational-legal authority. For instance, revolutionary leaders may be succeeded by constitutions or legal systems that institutionalize their principles, as with George Washington’s influence being preserved in the U.S. Constitution.

Weber’s three types of authority—traditional, charismatic, and rational-legal—offer a framework to understand why people accept authority in different contexts and how leaders can maintain control within social groups. Each type of authority brings unique strengths: traditional authority provides continuity, charismatic authority energizes and mobilizes followers, and rational-legal authority ensures consistent rule-based governance. By examining these authority types, we gain insights into the diverse ways leadership is legitimized, maintained, and challenged, shaping social groups and influencing the stability and adaptability of societies as they evolve.

Group Size & Dynamics: Georg Simmel’s Dyads, Triads, and Larger Groups

When studying sociology, it’s easy to think about society in terms of large-scale structures, such as governments, economies, or cultures. However, German sociologist Georg Simmel (1858-1918) took a different approach, focusing on the micro-level dynamics of small groups. Simmel, a foundational figure in sociology, was interested in how social interaction itself—at its most intimate and basic level—shapes society. To him, understanding the quantitative and qualitative differences in group sizes could reveal profound insights about social relationships and human behavior. His study of dyads and triads remains an essential foundation in understanding group dynamics.

Simmel described the dyad as the most basic form of social group. A dyad consists of only two people, such as a couple, two close friends, or a parent and child. According to Simmel, dyads are inherently intimate because they require each member’s full participation. Without mutual engagement, the dyad simply cannot exist; if one person leaves, the group dissolves. This makes dyads unique among social groups, as they rely entirely on the commitment and presence of both individuals.

Because of this exclusivity, dyads often foster deep emotional bonds. In a dyad, there are no outside influences or third parties to mediate, which means interactions are direct and personal. This can lead to intense connections, as seen in romantic relationships or close friendships, where individuals rely on each other for emotional support and companionship. However, Simmel also pointed out the fragility of these groups. The absence of a third person means there is no one to act as a buffer or mediator. Any conflict or issue in a dyad can feel more intense because there’s no external perspective to help resolve it.

Adding a third person to a dyad creates a triad, a group of three, which brings about an entirely different set of dynamics. In a triad, individual relationships within the group can shift and create alliances or coalitions. This new complexity changes how group members interact, as two members may form a closer bond, leaving the third person more isolated or even feeling like an outsider. This formation of alliances introduces an element of power dynamics that simply doesn’t exist in dyads.

For example, consider a group of three friends. The dynamics can shift based on alliances and preferences, with two friends occasionally forming a tighter bond that can make the third friend feel excluded. This possibility of coalition-building can also serve as a source of stability. Unlike in a dyad, where a conflict might threaten the group’s existence, a triad can survive even if one member temporarily withdraws. Thus, triads are structurally more stable but emotionally more complex, as the presence of three people allows for negotiation, competition, and mediation in ways that dyads cannot accommodate.

Simmel noted that triads allow for greater flexibility in social interactions. The third person can serve as a mediator during conflicts between the other two, easing tension and promoting group cohesion. At the same time, the introduction of a third perspective can facilitate decision-making and foster creativity, as more ideas are brought into the conversation. However, the presence of alliances and the possibility of exclusion also make triads more prone to internal conflicts than dyads.

As groups grow beyond three members, the dynamics shift yet again. Larger groups cannot rely on the intimate connections that characterize dyads and triads. Instead, they require more formal structures, such as hierarchies, roles, and social norms, to maintain organization and cohesion. In larger groups, individual members might no longer interact directly with everyone else, leading to the development of sub-groups or cliques. This transition from personal connection to formal structure marks a significant change in how members experience and relate to the group.

Simmel argued that as groups expand, they allow individuals more freedom, as personal relationships play a less central role. For instance, in a large group or organization, members are less likely to be scrutinized as individuals and can take on roles that suit their specific skills or interests. However, this also means that relationships within larger groups are often less personal and more functional. The focus shifts from maintaining intimate bonds to achieving collective goals, which necessitates a division of labor and a more formalized system of interaction.

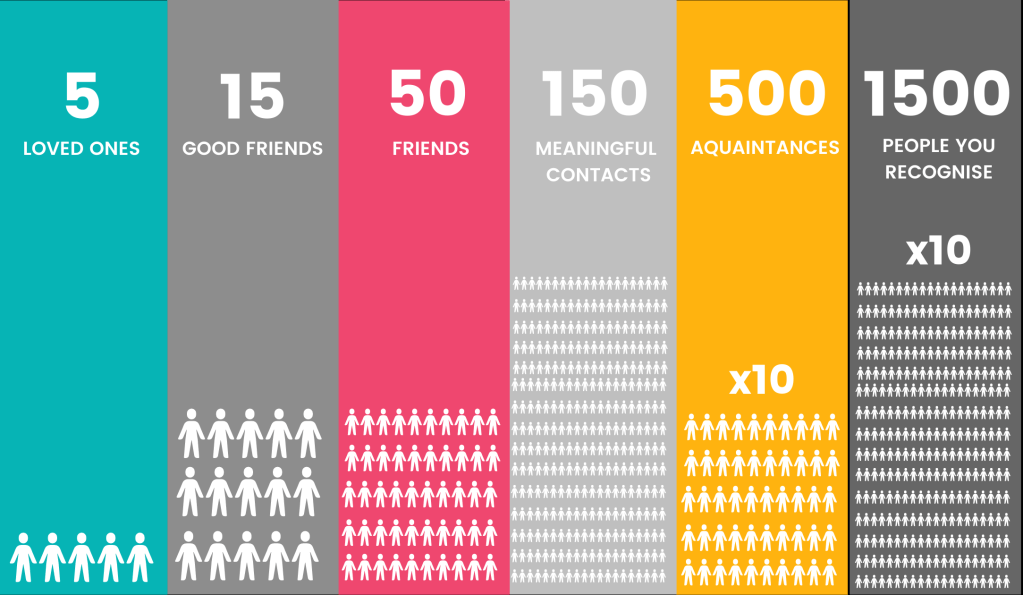

Simmel’s insights into group size laid the groundwork for further exploration of social dynamics. Building on this foundation, anthropologist Robin Dunbar introduced the concept of the Dunbar Number in the 1990s. Dunbar’s research suggested that humans have a cognitive limit to the number of stable social relationships they can maintain, estimated to be around 150 people. According to Dunbar, groups larger than this threshold require formal rules and structures to function effectively, as individual relationships alone are insufficient for maintaining cohesion and order.

The Dunbar Number supports Simmel’s idea that as groups grow, they become less intimate and more dependent on organizational frameworks. In a small group, personal connections are the primary source of social cohesion, but in larger groups, individuals rely on rules, roles, and institutions to navigate interactions. Dunbar’s work provides a quantitative extension to Simmel’s theory, suggesting that the complexities introduced by larger group sizes are not just social but also cognitive.

Simmel’s exploration of dyads and triads offers a profound understanding of how group size impacts social interactions. His work shows that as groups grow, they transition from intimate, direct relationships to complex structures that require mediation, alliances, and formal rules. The addition of each member fundamentally changes the dynamics within a group, shaping how individuals relate to each other and to the group as a whole. Simmel’s insights, later expanded by Dunbar, highlight the delicate balance between intimacy and complexity in human social life, illustrating how something as simple as group size can influence the structure and stability of relationships. For students of sociology, these ideas underscore the importance of examining not only the “who” and “why” of social groups but also the “how” of group dynamics and organization.

Rationalization & its Discontents

As we have seen, social groups form the backbone of society, shaping how individuals interact, organize, and navigate the world together. From informal gatherings to structured organizations, social groups vary greatly in size, purpose, and organization. Sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920) recognized the growing complexity of these groups in modern society, particularly as they became increasingly governed by rational systems aimed at achieving efficiency and consistency. His theory of bureaucracy presents a structured framework through which social groups manage large-scale tasks, emphasizing clear rules, roles, and hierarchies. However, Weber also warned of the potential downsides of rationalized systems, where rigid structures and impersonal processes could overshadow human values and ethical considerations. Through examining Weber’s ideas on bureaucracy and the concept of McDonaldization by George Ritzer (1940-Present), we see how rationalization influences social groups—both in supporting organizational efficiency and in potentially creating unintended, dehumanizing effects. This exploration provides valuable insights into the balance between order and humanity within the social groups that define our society.

Max Weber’s Concept of Bureaucratic Rationalization

Sociologist Max Weber viewed bureaucracy as a hallmark of modern society, representing the shift toward rationalization—the idea that society increasingly relies on efficiency, predictability, and logical order rather than traditions or emotions. In Weber’s view, bureaucracy is a rational organizational structure designed to handle large, complex tasks by breaking them down into specific roles and processes. This structure allows organizations to operate in a systematic and consistent manner, even as they grow in size and complexity.

At the heart of Weber’s theory is the concept of formal rationality, where each action is governed by rules, regulations, and a clear hierarchy to ensure efficiency and uniformity. In a bureaucratic organization, employees follow standardized procedures to achieve a common mission, reducing the uncertainty that can arise from individual judgment or informal practices. According to Weber, formal rationality is what enables bureaucracy to respond to the demands of modernity—particularly as societies become more interconnected and reliant on large-scale operations, such as governments, corporations, and educational institutions.

Weber identified several defining features that characterize a bureaucratic organization:

- Hierarchy of Order: Bureaucracies have a clear chain of command where each level has authority over the one below and reports to the one above. This structure establishes clear responsibilities and creates order, ensuring that tasks are supervised at each level.

- Written Rules and Regulations: Bureaucracies rely on formalized rules to maintain consistency across their operations. These written guidelines dictate how tasks are performed, promoting uniformity and allowing the organization to function predictably.

- Full-Time, Salaried Officials: Employees within bureaucracies are generally hired as full-time, salaried workers who are expected to maintain professional commitment to their roles. This distinction separates bureaucratic staff from volunteers or temporary workers, emphasizing continuity and expertise within the organization.

- Division of Labor: Bureaucracies are highly specialized, with each position assigned specific duties and responsibilities. This division of labor enhances productivity by allowing employees to focus on their particular roles, contributing to the organization’s overall goals more efficiently.

- Impersonality: Bureaucracies operate on a system of impersonal relationships, where decisions are based on objective rules rather than personal preferences or emotions. This impersonal approach ensures that policies are applied uniformly to all members, reinforcing fairness and neutrality.

A hospital provides a clear example of Weber’s bureaucratic structure. Hospitals are highly organized environments designed to deliver healthcare services efficiently to large numbers of patients. Within a hospital, there are various departments, such as emergency, radiology, surgery, and administration, each serving a specialized function. This division of labor allows doctors, nurses, technicians, and support staff to focus on their specific roles, contributing to the hospital’s overall mission of patient care.

The hospital’s hierarchical structure ensures that authority is clearly defined. For instance, administrators oversee the hospital’s operations, while department heads manage specific areas, such as surgery or intensive care. Each layer of management has a distinct role in guiding and supervising tasks within the hospital’s workflow. This hierarchy enables quick decision-making and a structured response to emergencies.

Furthermore, hospitals rely heavily on written protocols for patient care. For example, there are standardized procedures for administering medication, conducting surgeries, and discharging patients. These written guidelines ensure that every patient receives consistent, quality care and that staff have clear expectations for performing their duties.

Finally, the impersonal nature of bureaucracy is evident in hospitals as well. Staff members are expected to follow the same rules and protocols for all patients, regardless of personal relationships. This impartiality is crucial in healthcare, as it promotes fairness and maintains a focus on patient needs over personal preferences.

Weber’s concept of bureaucracy helps explain why hospitals, despite being large and complex organizations, can deliver specialized care consistently and efficiently. The hierarchical organization, reliance on written procedures, and specialized roles allow hospitals to function as rational entities that prioritize patient care within a structured system. This example illustrates Weber’s belief that bureaucracy is a rational solution for organizing complex tasks, especially as societies grow and demand greater efficiency from institutions.

George Ritzer’s Theory of McDonaldization

Building on the ideas of Max Weber, sociologist George Ritzer introduced the concept of McDonaldization in his 1993 book, TheMcDonaldization of Society. Ritzer uses McDonald’s, the fast-food giant, as a metaphor for how modern society increasingly organizes itself around principles of efficiency, predictability, calculability, and control—principles originally identified in Weber’s theory of rationalization and bureaucracy. According to Ritzer, McDonaldization describes a process in which the organizational principles of fast-food restaurants have come to dominate many sectors of society, from healthcare and education to retail and entertainment.

Ritzer identifies four key components of McDonaldization that reflect the rationalized and bureaucratic structure Weber described, but taken to a more extreme level:

- Efficiency: In McDonaldization, efficiency is about finding the quickest and least wasteful way to accomplish a task. Just as fast-food restaurants streamline food preparation and serving, other sectors adopt practices to minimize time and effort. For example, in retail, self-checkout machines allow customers to process their purchases quickly without assistance. While efficiency may seem beneficial, Ritzer argues that this emphasis can lead to a loss of quality and personalization, as tasks are simplified for speed rather than for value.

- Predictability: McDonaldization emphasizes making products and experiences predictable and uniform. At McDonald’s, for instance, a burger in New York will look and taste the same as one in Tokyo. This predictability appeals to customers seeking consistency, but it can also lead to standardized, impersonal experiences. In healthcare, for example, hospitals often use standardized treatment protocols to ensure consistency in care, which can improve efficiency but may not accommodate individual patient needs.

- Calculability: Ritzer argues that McDonaldization places a high value on quantifiable aspects of products and services, like size, speed, and cost, rather than quality. In a McDonaldized system, the focus is often on “more is better.” For example, fast-food menus might emphasize portion sizes or the number of items in a combo meal. In education, this calculable approach can be seen in standardized testing, where students’ success is measured by scores rather than by a deeper understanding of the material.

- Control: Control in McDonaldization refers to the use of technology and standardized practices to manage and regulate both employees and customers. In fast-food restaurants, for instance, cooking processes are automated to ensure uniformity, reducing human error. This principle extends to other areas, like automated customer service in retail or online check-ins at airports. Control can increase efficiency and minimize variability, but it also limits human creativity and agency, reducing interactions to scripted, mechanized experiences.

Hospitals, like fast-food chains, have adopted a model that emphasizes efficiency, predictability, calculability, and control to manage the complexities of modern healthcare. This approach ensures that hospitals can handle high volumes of patients and streamline procedures, but it also shapes the hospital experience in significant ways.

- Efficiency: Efficiency in hospitals focuses on providing patient care in the quickest and least resource-intensive way possible. For example, in emergency rooms, patient intake processes are streamlined to assess and triage patients rapidly. Hospitals often implement “fast-track” systems where patients with minor ailments are treated quickly to free up resources for more critical cases. This is similar to the assembly-line model of fast-food restaurants, where tasks are broken down to maximize speed. Hospitals design workflows so that each healthcare professional has a specific role, from intake nurses to lab technicians, ensuring that patients move through the system with minimal delays. Although efficient, this approach can sometimes feel impersonal as interactions are optimized for speed rather than individualized attention.

- Predictability: Predictability in hospitals is achieved through standardization. Most hospitals follow strict protocols and treatment guidelines for a wide array of medical conditions. For example, a patient presenting with chest pain might be placed on a standardized pathway for evaluating heart attack risk, involving set tests, medications, and observation periods. This standardized approach ensures that patients receive consistent care regardless of the hospital or healthcare provider they see, mirroring the way McDonald’s offers the same products at every location. In a hospital, predictability helps minimize errors and ensures that care is uniform, but it can limit flexibility, sometimes preventing healthcare providers from tailoring care to individual patient needs.

- Calculability: Hospitals often prioritize measurable outcomes, such as wait times, the number of patients treated, and bed turnover rates. These metrics allow administrators to evaluate hospital performance quantitatively. For instance, hospitals may set goals for discharge times in surgical units, aiming to move patients out within a specific timeframe to open beds for new patients. This focus on numbers mirrors the emphasis on quantity in fast-food chains, where success is measured by the number of burgers sold rather than customer experience or nutritional quality. In hospitals, calculability can ensure efficient use of resources, but it may also lead to pressure on staff to prioritize throughput over the quality of patient interactions.

- Control: In hospitals, control is achieved largely through technology and protocols that limit variability. For instance, electronic health record (EHR) systems guide healthcare providers through specific steps during patient visits, from recording symptoms to ordering tests. These systems are designed to reduce errors and ensure consistency, as every healthcare provider follows the same procedures. In addition, medication dispensing systems, such as automated pharmacy robots, help standardize dosage and reduce human error. This approach is similar to the mechanization in fast-food kitchens, where technology dictates cooking times and assembly processes. In hospitals, control over procedures enhances safety and consistency but can make the care process feel mechanical, with limited opportunities for personalized patient-provider interactions.

In hospitals, McDonaldization brings benefits in terms of efficiency, predictability, calculability, and control, allowing these institutions to handle large patient volumes with a high degree of consistency. However, this structure also shapes the nature of care delivery, focusing on streamlined processes that prioritize speed and uniformity. While patients receive reliable and standardized treatment, the McDonaldized approach can make the healthcare experience feel standardized and impersonal, reflecting the trade-offs inherent in applying fast-food principles to complex human services like healthcare.

The Irrationality of Rationality

For Max Weber, rationalization is a double-edged sword. While bureaucracy brings order and consistency to complex tasks, it also creates an “iron cage” of rules that can trap individuals within dehumanizing processes. In a bureaucratic system, individuals are expected to follow established procedures without questioning their purpose or ethical implications. This adherence to rules over judgment can lead to irrational outcomes—situations where the process becomes more important than the people it serves. For example, in a hospital (our earlier example of McDonaldization), a strict emphasis on efficiency and speed might result in patients feeling alienated, overlooked, or receiving suboptimal care due to rigid time constraints.

Weber believed that in a rationalized society, individuals could become mere cogs in a machine, blindly following orders within bureaucratic systems that prioritize goals over humanity. This approach creates a society where people prioritize process over empathy, often leading to situations where rationalized systems produce results that contradict their intended purpose of benefiting human society.

Instead of the “iron cage,” George Ritzer used the term “irrationality of rationality” to describe the downsides of McDonaldization. He used numerous examples to showcase how institutions build on McDonaldized principles often sacrifice depth, personal engagement, and ethical considerations in the pursuit of efficiency and uniformity. The rational system, intended to create order and functionality, ends up creating rigid and dehumanizing experiences for those within it. For example, in a McDonaldized education system, the emphasis on standardized testing (calculability) and rapid instruction (efficiency) can undermine meaningful learning by reducing education to a series of rote tasks in pursuit of increasingly hollow grades. This shift makes grades feel more like a commodity, valued for their role in securing future opportunities rather than as an accurate reflection of knowledge or critical understanding.

Together, Weber and Ritzer illustrate how highly rationalized systems, while intended to bring order and efficiency, can lead to dehumanizing outcomes when detached from ethical considerations. This “irrationality of rationality” serves as a cautionary insight, reminding us that the pursuit of efficiency, control, and predictability must be balanced with human values and ethical awareness. For students, this section underscores the importance of critically examining the systems we create and participate in, understanding that rational structures can sometimes lead to unintended consequences that impact society on both personal and moral levels.

The Holocaust: The Ultimate Irrationality of Rationality

The Holocaust was a state-coordinated genocide during World War II, led by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime, resulting in the murder of six million Jews and millions of other victims deemed “undesirable.” The Nazi system of concentration and death camps subjected individuals to forced labor, starvation, and mass executions on an industrial scale. While the Holocaust is often associated with ideology and hatred, sociologist Zygmunt Bauman (1925-2017) presents a different and unsettling perspective: that the Holocaust was not just an atrocity of unchecked hate but a tragic outcome of rational, bureaucratic processes. Born in Poland in 1925, Bauman experienced anti-Semitism firsthand, narrowly escaping Nazi persecution by fleeing to the Soviet Union. These experiences profoundly shaped his work, leading him to question how rationality—typically seen as a force for societal progress—could support devastating outcomes.

In his 1989 book Modernity and the Holocaust, Bauman argues that the Holocaust was not an anomaly of modern civilization but a grim fulfillment of its rational capabilities. According to him, the Nazi regime implemented genocide with an industrial, bureaucratic approach, organizing atrocities through clear hierarchies, impersonal rules, and procedural efficiency. Concentration camps operated with logistical precision and record-keeping comparable to any modern enterprise, revealing how a “rational” approach could facilitate horrific actions.

Bauman’s analysis shows how principles of bureaucracy, such as division of labor and adherence to rules, enabled individuals to detach from the moral implications of their roles. For example, railway officials who scheduled trains to concentration camps saw themselves as administrators, focused on efficiency without considering the consequences. This “disconnection” reflects what Bauman termed the “irrationality of rationality,” where prioritizing efficiency and order can obscure ethical responsibility.

When comparing Bauman’s insights to those of Weber and Ritzer, we see how rationalized systems intended for order and efficiency can become dehumanizing when ethics are absent. Bauman’s work offers a profound reminder that the pursuit of rational goals—efficiency, predictability, control—must be balanced with a moral awareness to prevent unintended and potentially disastrous consequences.

Conclusion

Social groups are at the heart of human society, connecting individuals through shared roles, goals, and relationships. From the deep emotional bonds of primary groups to the goal-oriented structures of secondary groups, each type of social group offers unique insights into how we navigate our social world. The work of theorists like Robert Putnam, Max Weber, and Georg Simmel reveals the intricate ways social capital, authority, and group size shape group dynamics, influencing everything from intimate friendships to large-scale organizations.

Yet, as we’ve seen, these structures come with complexities and challenges. Rationalization, while bringing efficiency and order, can sometimes dehumanize or overshadow the values that make social groups meaningful. By understanding these dynamics and reflecting on their implications, we can better navigate our own roles within society, balancing the pursuit of structure and efficiency with the need for empathy and ethical awareness. In doing so, we strengthen not only our social groups but also the communities and societies they sustain.

Key Terms

Aggregate: A gathering of people in the same place without shared goals or interaction beyond the immediate setting.

- Example: People in line at a coffee shop or waiting at a bus stop.

Authority: The legitimate power or right to make decisions, control resources, and enforce obedience within a social structure.

- Example: A judge in a courtroom has authority over legal proceedings.

Bonding Social Capital: Strong connections within a homogenous group, such as family or close friends, which offer emotional support and reinforce group identity.

- Example: A family relying on each other during challenging times.

Bridging Social Capital: Connections across diverse groups, enabling access to new resources and perspectives.

- Example: A professional networking group that brings people from different industries together.

Bureaucracy: An organizational structure defined by Max Weber that is marked by clear hierarchies, formal rules, and a focus on efficiency and consistency.

- Example: Government agencies, where roles and processes are highly standardized.

Category: A group of people linked by a shared characteristic but lacking interaction or a sense of belonging.

- Example: People over age 65 or all college students form categories by age or status.

Charismatic Authority: Authority based on an individual’s exceptional personal qualities and influence.

- Example: Martin Luther King Jr., whose charisma and vision inspired followers during the civil rights movement.

Dyad: The simplest social group, consisting of two individuals, where interaction is intimate and direct.

- Example: A close friendship between two people.

Dunbar Number: Anthropologist Robin Dunbar’s concept suggesting that humans can maintain stable social relationships with around 150 people.

- Example: The typical size of a close-knit community or village.

Expressive Function: The role of a group in meeting emotional needs and providing personal support, typically found in primary groups.

- Example: Turning to a best friend for comfort after a breakup rather than a casual acquaintance.

In-Group: A group with which an individual identifies closely, fostering a sense of loyalty and belonging.

- Example: National or religious identity, where individuals feel connected to others who share similar values.

Instrumental Function: A group’s role in accomplishing specific tasks, usually in more formal, goal-oriented settings like secondary groups.

- Example: Reaching out to colleagues for help with a work project rather than seeking support from family.

Iron Cage: Max Weber’s term describing how individuals can feel trapped in overly rationalized systems that prioritize efficiency over human values.

- Example: A corporate job where employees follow strict procedures, feeling detached from personal fulfillment.

McDonaldization: George Ritzer’s idea that many aspects of society are becoming standardized around efficiency, predictability, calculability, and control, similar to the operations of a fast-food chain.

- Example: Self-checkout systems in retail stores to speed up the customer experience.

Out-Group: A group perceived as different or in opposition to one’s in-group, sometimes resulting in rivalry or tension.

- Example: Someone with strong national pride (in-group) viewing people from other countries as outsiders (out-group).

Primary Groups: Small, intimate groups with deep, lasting emotional bonds that play a central role in personal identity and values.

- Example: Families and close friends, where connections are based on personal affection and support rather than goals.

Rational-Legal Authority: Authority based on formal rules and laws, where power is granted by a legal framework.

- Example: An elected president, whose authority is defined by a constitution.

Reference Groups: Groups that serve as a standard for self-evaluation and influence personal values, behaviors, and attitudes.

- Example: Peer groups that influence fashion choices or family members shaping political beliefs.

Secondary Groups: Larger, task-focused groups with more formal, less personal interactions, often formed to achieve specific objectives.

- Example: A workplace team focused on tasks or a college class working toward academic goals.

Social Capital: The networks, relationships, and norms of trust and reciprocity that exist within a society, allowing individuals to work together more effectively.

- Example: Neighborhood associations that come together to improve local amenities.

Social Groups: A collection of individuals connected by a shared purpose and regular interaction, distinguished from random gatherings by their mutual goals and expectations.

- Example: A soccer team with players who train together and follow shared rules, or a workplace marketing team collaborating on projects.

Traditional Authority: Power that is legitimized by longstanding customs and cultural practices.

- Example: A monarchy, where a king or queen rules based on hereditary right.

Triad: A social group of three, where dynamics become more complex, allowing for alliances and mediation.

- Example: A group of three friends, where two may sometimes bond more closely, shifting dynamics.

Reflective Questions

- How do statuses and roles shape the way people behave in everyday life, and what are some examples of how these expectations can both guide and constrain individual actions?

- What is the difference between ascribed status and achieved status, and how do these ideas help us understand how opportunity and inequality are distributed in society?

- What does it mean to say that rational systems can produce irrational outcomes, and how do examples like fast food or education help us understand this idea?

- Why do sociologists emphasize the importance of institutions in organizing society, and how do these structures influence what individuals can or cannot do?