Table of Contents

- Learning Objectives

- Introduction

- Social Order, Conformity and Deviance

- Solomon Asch Experiment on Conformity

- Theories on Deviance

- Mass Incarceration as the New Jim Crow

- Conclusion

- Key Concepts

- Reflection Questions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, students will be able to:

- Define deviance and conformity in sociological terms, and distinguish between deviance, crime, and the societal reactions that follow each.

- Analyze the role of sanctions—both formal and informal, positive and negative—in reinforcing social norms and maintaining order in everyday settings.

- Evaluate Emile Durkheim’s functionalist theory of deviance, including the concepts of norm clarification, social cohesion, innovation, and anomie.

- Explain symbolic interactionist perspectives on deviance, particularly Howard Becker’s labeling theory and the concepts of primary and secondary deviance.

- Describe the Solomon Asch conformity experiment and interpret how group pressure and social context shape individual behaviors and perceptions.

- Interpret the key claims and critiques of Broken Windows Theory, including its real-world application in policing and its relationship to social order and urban control.

- Apply conflict theory to the U.S. criminal justice system, using Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow to understand how mass incarceration functions as a modern system of racial and class-based social control.

- Assess how deviance is socially constructed, shaped by power dynamics, labeling processes, and historical context, rather than inherent in particular behaviors.

- Critically evaluate the ethical and social implications of deviance control strategies, including policing, incarceration, and public perception, particularly in relation to race, class, and social inequality.

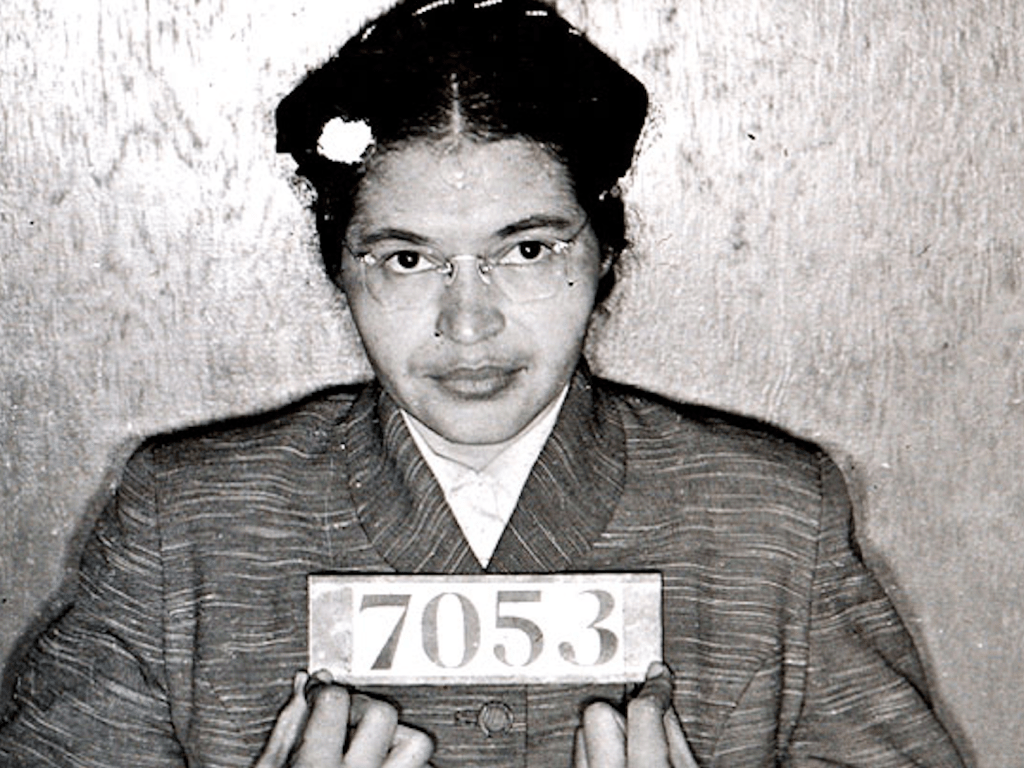

- Reflect on the transformative potential of deviance, as illustrated by figures like Rosa Parks and movements that challenge unjust norms and systems.

Introduction

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks, a 42-year-old African American seamstress, boarded a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, and took a seat in the “colored” section. When the bus filled up, Parks was ordered to give her seat to a white passenger. Quietly and firmly, she refused. This small but resolute act of defiance led to her arrest and ignited the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement. Parks’ refusal to conform to unjust social norms highlighted the power of deviance to challenge entrenched systems of inequality and inspire transformative change.

Rosa Parks’ story illustrates that social order is not inherently just or fair; it reflects the norms, values, and power structures of a given society. Conformity, the act of adhering to societal expectations, is often essential for maintaining order and predictability in daily life. However, when those norms are rooted in injustice, deviance—the act of resisting or breaking those norms—becomes a powerful tool for social critique and change. Parks’ arrest was not simply a moment of disobedience; it was a profound challenge to the social order of the segregated South, forcing a reckoning with systemic racism and inequality.

This chapter explores the dynamic interplay between conformity, deviance, and social control. By examining key sociological theories and real-world examples, we delve into how societies establish norms, enforce compliance, and respond to those who deviate. Rosa Parks’ legacy reminds us that deviance is not always destructive—it can be a powerful force for progress, revealing the ways in which social order is constructed, upheld, and, at times, fundamentally reimagined.

Social Order, Conformity and Deviance

Societies rely on a complex web of norms, values, and rules to maintain social order, allowing individuals to coexist and interact predictably and constructively. This social order is upheld through a balance of conformity and regulation, encouraging people to act in ways that align with societal expectations. Conformity, the process by which individuals align their behaviors and beliefs with those of the larger group, is crucial for a cohesive society. Institutions like schools, families, workplaces, and religious organizations play essential roles in promoting conformity through socialization, teaching people to internalize behaviors that fit societal norms. However, not all behaviors align with these expectations, leading to what sociologists define as deviance.

Deviance includes any behavior or belief that strays from societal norms, but it’s important to note that deviance is not inherently negative or criminal. Deviance is a broad concept, encompassing actions that challenge the status quo, whether through innovation, harmless individuality, or rebellion against social norms. For example, unconventional styles of dress or nontraditional career choices may be considered deviant but are not illegal. In contrast, crime refers specifically to behaviors that violate established laws, which society enforces through formal sanctions. However, not all crimes are viewed as deviant—actions like speeding or jaywalking may technically break the law but are widely tolerated or overlooked. Conversely, not all deviant actions are crimes, as society may disapprove of certain behaviors without imposing legal penalties. The distinction between deviance and crime reflects how society’s norms influence our view of behavior and how laws formalize certain expectations.

To regulate behavior and promote conformity, societies rely on sanctions, which are responses that encourage people to adhere to norms or deter them from deviant acts. Formal sanctions are structured responses by official institutions, such as fines, arrests, or promotions. For instance, someone who engages in theft may face imprisonment—a negative formal sanction designed to punish and deter criminal behavior. Alternatively, informal sanctions occur in everyday interactions, based on social feedback rather than institutional rules. A person might receive disapproving glances for speaking loudly in a quiet setting—an informal negative sanction—or they might receive praise for helping a neighbor, an informal positive sanction.

Sanctions can be both positive, rewarding conformity, and negative, discouraging deviance. Positive sanctions include rewards for adhering to social norms, such as promotions, praise, or recognition, which reinforce valued behaviors. Negative sanctions are penalties intended to deter deviant behavior, ranging from social disapproval to legal consequences like fines or jail time. Through these various types of sanctions, societies continually reinforce social order, guiding individuals toward behavior that aligns with collective expectations while also adapting norms and laws to reflect evolving values.

Solomon Asch Experiment on Conformity

The Solomon Asch Conformity Experiment (1951) headed by psychologist, Solomon Asch, is a landmark study that delves into how social influence affects individual decision-making, especially when faced with the choice of conforming or deviating from the group. Building on the sociological concepts of conformity and deviance, Asch set out to test whether people would align their views with a group’s opinion, even if that opinion was obviously incorrect. This experiment illustrates the power of group pressure and provides valuable insights into the social dynamics that drive conformity and resistance.

Asch’s experiment involved groups of eight participants, with only one true test subject in each group, while the remaining seven were confederates (actors aware of the experiment’s aim). Participants were shown a reference line and three comparison lines, then asked to identify which comparison line matched the reference line in length. The confederates were instructed to give an incorrect answer aloud in certain trials, creating a situation where the test subject faced the decision of either agreeing with the group’s obvious mistake or giving the correct answer independently. This setup tested how social pressure from a unanimous group could influence an individual’s judgment.

The results of the experiment revealed the profound influence of group pressure on individual choices. About 32% of test subjects conformed with the group’s incorrect answer in all trials, while 75% conformed at least once. Interestingly, 25% of participants remained unaffected by the group pressure and consistently gave the correct answer. These findings indicate that, in many cases, people prioritize group harmony and a sense of belonging over their own perception of reality, even when the correct answer is clear.

These experiments sheds light on how deeply ingrained the desire to conform is, often overriding personal judgment in favor of fitting in with the group. This tendency to conform, even when the group’s opinion is clearly wrong, highlights the social cost of deviating from group norms. The experiment suggests that conformity is not solely a matter of knowledge but also an emotional response to group dynamics. Furthermore, Asch’s work underscores the broader implications for understanding social phenomena like socialization, groupthink, and the ethical challenges of following the crowd. These findings illustrate that conformity is influenced by the cultural and social environment, and the willingness to conform can come at the expense of critical thinking and individual moral judgment.

The Asch Conformity Experiment reveals that conformity and deviance are deeply influenced by social pressures rather than just personal choice. Even when confronted with clear evidence, individuals often conform to group opinion, illustrating the powerful role of social influence in shaping behavior. Asch’s experiment remains crucial for understanding how social norms are reinforced and how individuals navigate the tension between the need to belong and the desire to stay true to their beliefs. Through this study, Asch highlights the delicate balance individuals must maintain between fitting in and standing out, offering a foundational perspective on the complexities of social behavior.

OPITIONAL: Video of the Asch Conformity Experiments

Theories on Deviance

Functionalism: Emile Durkheim

The sociologist Emile Durkheim (1846-1917) offered an original view on deviance. Instead of seeing deviant behavior solely as a problem, he argued that it plays a crucial role in maintaining a healthy society. From his perspective, deviance serves several important functions that support social order, even if the behavior itself seems disruptive. Through this lens, Durkheim’s approach helps us see that deviance isn’t simply negative but essential for the growth and cohesion of society.

Why Deviance is Functional

Durkheim outlined specific ways in which deviance contributes to social stability and change. Here are the primary functions he identified:

- Clarifying Social Norms: Deviant behavior draws attention to the rules and values of a society by prompting reactions from those who uphold these norms. For example, when someone disrupts a classroom by using their phone during a lecture, the instructor and other students may react by reinforcing expectations of classroom respect and focus. This reaction helps clarify the norm that during class, respectful attention is expected. Deviant actions, therefore, act as reminders of the boundaries within a community, reinforcing the behaviors that are valued.

- Encouraging Social Change: Durkheim believed that deviance could also inspire positive change. When individuals or groups push back against outdated or unjust norms, they can pave the way for new ideas and improvements. For instance, consider how social movements, like those for racial or gender equality, were once viewed as deviant but ultimately led to more inclusive laws and social practices. Even within the campus setting, students advocating for changes—like more accessible mental health services—might challenge the current status quo, leading to beneficial shifts in school policy.

- Fostering Social Unity: Deviance can strengthen social bonds when people unite in their response to it. When a community collectively condemns an act, like vandalism on campus, this shared reaction brings people together in support of common values. By reinforcing collective beliefs and uniting against perceived threats to social order, society strengthens its own cohesion.

Anomie & the Breakdown of Social Order

Durkheim introduced anomie, or a state of normlessness, to describe periods when society’s values and expectations break down, often during times of major social upheaval. During anomie, people may feel disconnected and uncertain about acceptable behavior. For instance, with the sudden shift to remote learning during COVID-19, students and instructors struggled to navigate expectations for attendance, participation, and workload without the usual in-person norms, leading to a temporary loss of social cohesion.

Durkheim argued that anomie increases the likelihood of deviant behavior, as individuals lack established norms to guide them. To restore order, society often adapts by creating new norms that address emerging circumstances. In the case of remote learning, schools gradually established guidelines around online class participation, attendance policies, and assignment deadlines, which helped reestablish structure and cohesion in a time of uncertainty.

In times of anomie, deviance can also drive social evolution, as individuals challenge outdated norms and experiment with new behaviors. For instance, the use of online resources for collaboration or even test-taking—sometimes considered deviant in traditional settings—led to new policies and approaches for academic integrity in virtual classrooms. As society adjusted to remote learning, it redefined acceptable behaviors and created new norms to reflect the unique demands of an online environment. Thus, while anomie creates uncertainty, it also offers communities opportunities to redefine and reinforce social order in response to changing needs.

Durkheim’s perspective on deviance challenges us to view it not just as a disruption but as an important part of social life that supports stability and growth. By clarifying norms, encouraging change, and uniting communities, deviance ultimately contributes to the resilience of society. Durkheim’s ideas remind us that behaviors outside the norm can prompt reflection and adaptation, supporting a community’s development and cohesion.

Symbolic Interactionism: Howard Becker & Labeling Theory

As we’ve explored, sociologists like Emile Durkheim have examined deviance through structural lenses, focusing on how social expectations and opportunities influence behavior. Building on this understanding, Labeling Theory, primarily developed by Howard Becker (1928-2003), introduces a new dimension by examining how social interactions and perceptions shape deviance. Labeling Theory falls under the umbrella of symbolic interactionism, emphasizing that deviance is not inherent in an action itself but arises from the labels and meanings assigned by society. Becker’s work underscores that deviance is a socially constructed concept, defined more by society’s reaction than by the act itself. This perspective provides valuable insight into how individuals are influenced not only by structural forces but also by the social processes and interactions that shape their identities.

Labeling Theory, rooted in social constructionism, argues that deviance is not inherent in an action but is a result of society’s reaction to it. Becker, a key figure in this theory, explained that deviance is created through a two-step social process. First, social groups establish rules that define acceptable behavior, which helps maintain order. When individuals violate these norms, society reacts by labeling them as deviant.

This labeling process is NOT neutral; it’s shaped by social power dynamics and context, which can vary significantly. For example, behaviors like drug use may be labeled differently depending on the group affected. During the crack epidemic, drug use was criminalized when it predominantly impacted Black Americans, but later, during the opioid crisis among White communities, addiction was more often framed as a public health issue rather than criminal deviance (Source).

This labeling also introduces the concepts of primary and secondary deviance. Primary deviance refers to an initial rule-breaking act, which might not affect an individual’s self-identity. For instance, a person might occasionally use marijuana without seeing themselves as “deviant.” However, when society repeatedly labels them as a “drug user” or “criminal,” they may internalize this identity, leading to secondary deviance. In this stage, the person begins to see themselves through the lens of society’s label, adopting behaviors that align with the label. Becker’s study, “Becoming a Marihuana User”(1953), illustrates this process, showing that marijuana use became “deviant” largely through social labeling and learned meaning rather than any inherent quality of the drug.

Ultimately, Labeling Theory emphasizes that deviance is socially constructed—defined and enforced by society based on power dynamics, social values, and context. This perspective challenges the notion of deviance as objective or universal, instead revealing how social groups wield the power to define and enforce norms that shape individuals’ identities and actions over time.

Labeling Theory expands our understanding of deviance by shifting the focus from individual actions to social perceptions and interactions. Howard Becker’s insights reveal that deviance is not an objective fact but a social process, where labels and societal reactions play a central role. This theory, along with concepts from Durkheim, encourages us to consider how social expectations and interactions define what is “normal” and what is “deviant.” By recognizing that deviance is often a reflection of society’s biases and structures, Labeling Theory offers a nuanced perspective on how individuals navigate their identities in the face of social judgment.

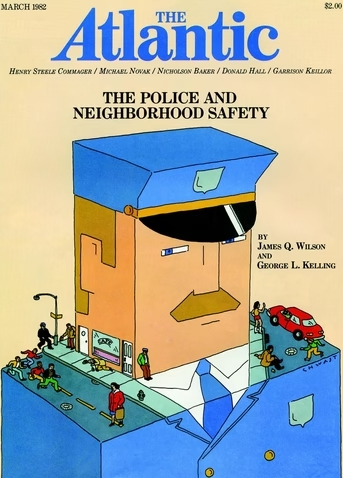

Broken Windows Theory

In the early 1980s, many American cities were grappling with rising crime rates, economic hardship, and visible signs of urban decay (Source). Neighborhoods faced increased rates of vandalism, drug use, and property crime, while abandoned buildings and deteriorating infrastructure became common sights. The economic recession of the late 1970s had left many urban areas under-resourced, leading to cuts in public services and a loss of jobs that intensified poverty and social instability. In this climate, city officials and residents grew increasingly concerned about the spread of urban disorder, fearing that unchecked minor crimes and visible neglect would lead to further social breakdown. Many began to believe that these outward signs of disorder might embolden more serious criminal activity and erode public safety and community morale.

In response to these concerns, social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling introduced Broken Windows Theory in a 1982 article published in The Atlantic titled “Broken Windows.” Their theory sought to address the relationship between minor signs of disorder and larger patterns of crime and public fear. Wilson and Kelling observed that even small indicators of neglect—like broken windows left unrepaired, graffiti, or public loitering—could signal that a neighborhood was vulnerable to crime, creating an atmosphere of lawlessness and diminishing residents’ sense of safety.

Broken Windows Theory posits that visible signs of disorder and minor offenses encourage an environment of lawlessness, ultimately fostering more serious criminal activities. Wilson and Kelling argued that if police, local authorities, and community members quickly addressed small signs of disorder, they could prevent neighborhoods from spiraling into crime hotspots. By maintaining a well-ordered environment, communities could deter further criminal behavior by signaling that deviance would not be tolerated.

An example of Broken Windows Theory in action is the crackdown on subway graffiti in New York City in the 1980s. City officials believed that graffiti symbolized neglect and lawlessness, which encouraged more serious crimes throughout the subway system. They implemented policies to clean trains and stations immediately after any graffiti appeared, showing that no sign of disorder would be left unchecked. This focus on removing graffiti was accompanied by increased enforcement against minor offenses like fare evasion, which authorities viewed as gateway actions to larger crimes. Over time, these actions contributed to a decline in crime in the subway, bolstering support for Broken Windows policing in broader public spaces.

Impact & Critiques of Broken Windows

Broken Windows Theory had a profound impact on law enforcement strategies, particularly in large cities during the 1990s. For example, in New York City, under newly elected mayor, Rudy Giuliani and Commisioner, William Bratton, the NYPD adopted “zero-tolerance” and “order-maintenance” policing strategies, focusing heavily on minor infractions—such as fare evasion, public drinking, and loitering—believing that these offenses could lead to an environment conducive to more serious crimes (Source). Advocates of Broken Windows policing pointed to reductions in crime rates in several cities, attributing these declines to the theory’s principles. In New York, for example, the crime rate dropped significantly in the 1990s, with city officials crediting Broken Windows policies for creating safer public spaces and restoring a sense of order (Source).

However, scholars and critics have raised significant concerns about the theory’s effectiveness and social implications. Sociologist Bernard Harcourt, in his book Illusion of Order, argues that there is little empirical evidence directly linking Broken Windows policing to decreases in serious crime, challenging the theory’s foundational assumption. He suggests that broader socioeconomic factors, such as economic growth and social welfare programs, may have been more influential in reducing crime than the policing of minor offenses.

Other scholars, such as Jeffrey Fagan, have criticized Broken Windows Theory for contributing to over-policing and racial profiling, particularly through practices like “stop-and-frisk” (Source). Fagan’s research highlights that the heavy focus on low-level offenses often led to racial disparities, with Black and Latino individuals disproportionately targeted for minor infractions. Fagan argues that Broken Windows policing fosters distrust between police and communities, as residents feel unfairly criminalized for minor actions.

These critiques have prompted cities to re-evaluate the implementation of Broken Windows policing, with a growing shift toward community-oriented strategies that emphasize building trust and addressing the root causes of crime rather than focusing exclusively on minor infractions.

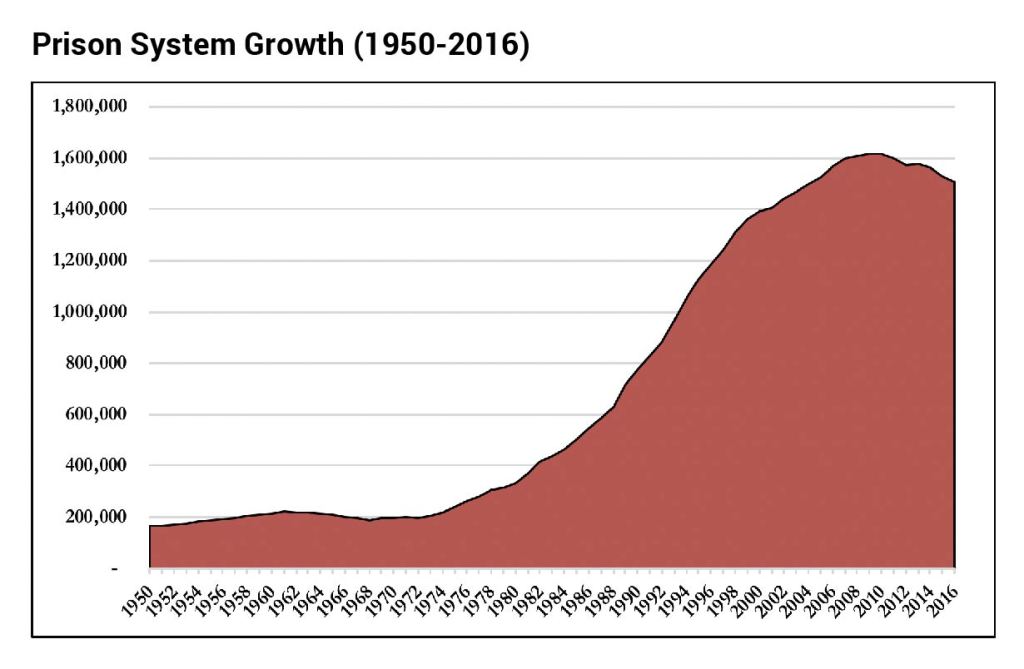

Mass Incarceration as the New Jim Crow

In her influential 2010 book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander argues that the United States’ criminal justice system functions as a modern racial caste system. While the U.S. has only 5% of the world’s population, it holds nearly 25% of the world’s prisoners, with over 2 million people currently incarcerated (Source). Men of color, particularly Black and Latino men, are disproportionately impacted: Black men are incarcerated at a rate nearly six times that of White men, and Latino men at twice the rate (Source). This overrepresentation is not solely the result of individual behaviors but reflects systemic racial biases that push these communities into cycles of criminalization and incarceration. Alexander argues that mass incarceration serves as a method of social control, reinforcing racial and economic inequalities by labeling individuals as “criminals” and stripping them of rights and opportunities. It can be argued that her work provides a modern application of conflict theory, which views social structures as inherently biased toward maintaining the power of dominant groups at the expense of marginalized ones, especially through criminalization and social exclusion.

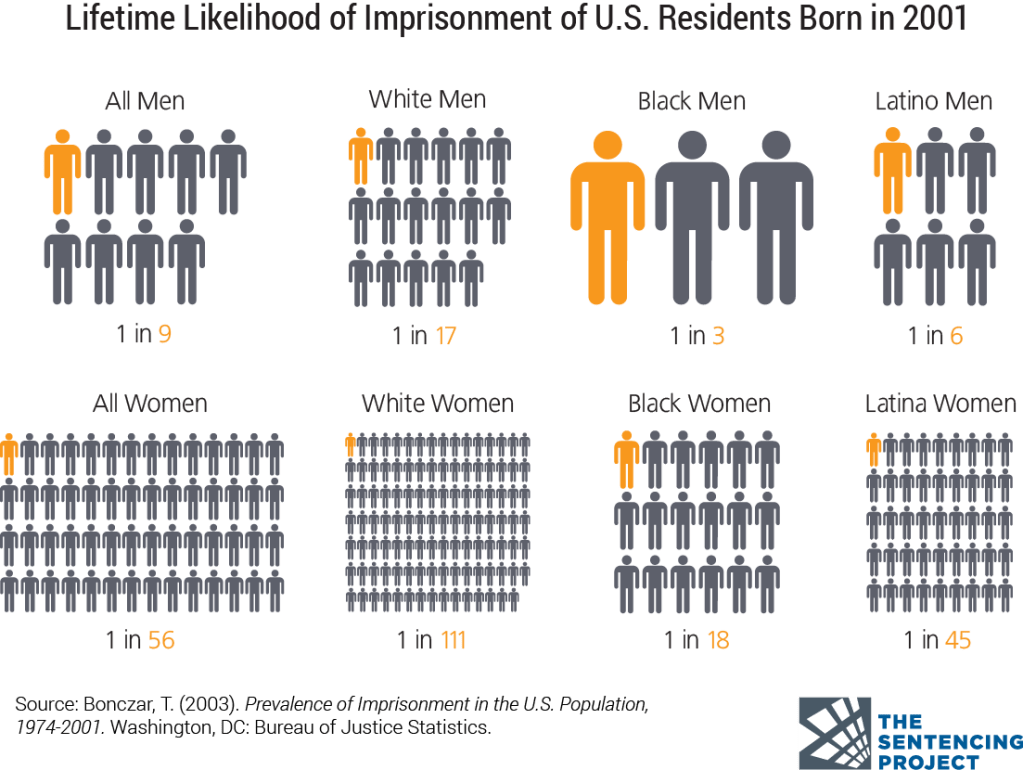

Visualizing Mass Incarceration & its Racial Disparities

Conflict Theory and the Criminal Justice System

The theoretical perspective of conflict theory examines how social institutions and norms reflect the interests of those in power. Rather than promoting equality or fairness, conflict theorists argue that laws and social structures are designed to maintain control and uphold the dominance of privileged groups. Alexander applies this lens to the criminal justice system, arguing that mass incarceration is not merely a consequence of crime but a deliberate mechanism to control minority populations and reinforce existing social hierarchies.

A stark example of this is the sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine offenses, which disproportionately affects Black communities. Despite similar rates of drug use across racial lines, laws implemented in the 1980s penalized crack cocaine—more commonly used in low-income Black communities—far more severely than powder cocaine, which was more frequently associated with affluent, predominantly White populations. Under these policies, individuals convicted of crack cocaine offenses often received sentences 100 times longer than those for powder cocaine, highlighting how legal structures can target specific communities and reinforce racial and economic inequalities. This disparity exemplifies how the law functions as a tool for maintaining racial and economic dominance by criminalizing behaviors more prevalent in specific communities, ultimately contributing to a racial caste system.

This analysis aligns with conflict theory’s assertion that institutions are used by powerful groups to impose norms, values, and rules that serve their interests while oppressing others. By structuring sentencing laws to disproportionately impact communities of color, many conflict theorists argue that the criminal justice system acts as a mechanism of social control rather than impartial justice, reinforcing the dominance of privileged groups and limiting the rights and opportunities of marginalized populations.

Criminalization, Labeling, and the Construction of Deviance

Alexander not only draws on conflict theory, but also labeling theory and the concept of the social construction of deviance to examine how society defines certain behaviors and groups as “criminal” based on power dynamics. Labeling theory suggests that deviance is not inherent in any act; rather, it is a label assigned by those in authority, often shaped by social biases. In The New Jim Crow, Alexander describes how minor offenses are disproportionately criminalized for people of color, especially in Black and Latino communities, resulting in a label of “criminal” that carries severe, lasting consequences. She argues that this process of criminalization, or systematically transforming specific behaviors and communities into persistent targets of legal and social control, mirrors the racial control mechanisms of the Jim Crow era. As a modern racial caste system, the “new Jim Crow” disproportionately subjects marginalized communities to heightened surveillance and policing, ensuring that the criminal label affects their social and economic opportunities.

This labeling often begins with primary deviance, where minor rule-breaking behaviors do not drastically impact an individual’s self-image. However, the criminal label quickly escalates to secondary deviance, as individuals internalize this identity and may feel forced into a deviant role. Through a cycle of disenfranchisement—such as exclusion from jobs, housing, and voting rights—individuals labeled as criminals find it increasingly difficult to escape the criminal justice system’s control. Alexander argues that the “new Jim Crow” system perpetuates deviance by disproportionately labeling and punishing marginalized groups, enforcing a cycle of poverty and social exclusion under the guise of “law and order.” This systemic process, she contends, functions as a modern form of racial control that parallels the segregation and disenfranchisement once upheld by Jim Crow laws.

Mass Incarceration as Social Control

One of the core ideas in conflict theory is that social control is maintained by those in power to suppress threats to their dominance. Alexander’s concept of mass incarceration fits this view, as it serves to control and manage the behavior of marginalized communities, primarily Black and Latino Americans. By criminalizing minor offenses and aggressively policing specific populations, the criminal justice system becomes a mechanism of social control. Once labeled as criminals, individuals from these communities face restricted access to resources, diminishing their political power and social mobility, and reinforcing the dominant group’s position.

Alexander argues that mass incarceration also creates a sense of “colorblindness” that obscures systemic racism. The system’s purported goal of maintaining public safety hides its actual function as a racial control strategy. This view aligns with conflict theory’s emphasis on how dominant groups manipulate social structures to maintain control without appearing overtly oppressive. By framing its policies as objective and colorblind, the system masks its true function as an instrument of racial and class-based oppression, consistent with conflict theory’s assertion that institutions are shaped to sustain inequalities and perpetuate control.

Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow provides a modern critique of the criminal justice system, highlighting how mass incarceration perpetuates racial inequalities under the pretense of legality. Her work closely aligns with conflict theory, demonstrating that social institutions, rather than serving justice or equality, often reflect and reinforce existing power dynamics. By linking the social construction of deviance to racial and economic inequalities, Alexander challenges the assumption that crime and punishment are impartial. Instead, she reveals how the criminal justice system functions to sustain the dominance of privileged groups and control marginalized communities, echoing conflict theory’s assertion that deviance and social control are tools of societal power. Her work calls for a reevaluation of how society defines and enforces deviance, urging us to question the biases embedded within these processes and consider the need for systemic change.

Criticisms of Alexander’s New Jim Crow

While Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow has been widely influential in highlighting the racial injustices of mass incarceration, it has also faced criticism from scholars and activists. One critique comes from legal scholars such as James Forman Jr., who argues in his book Locking Up Our Own that Alexander’s focus on the racialized nature of mass incarceration may overlook some of the complexities within the criminal justice system. Forman points out that Black communities have, at times, supported tough-on-crime policies due to concerns about crime within their neighborhoods, arguing that Alexander’s analysis may oversimplify the issue by portraying it strictly as a top-down racial caste system.

Others, like sociologist Loïc Wacquant, have critiqued Alexander’s work for not fully addressing the broader socioeconomic forces that contribute to mass incarceration. Wacquant argues that Alexander’s book emphasizes racial discrimination while potentially underplaying the effects of poverty and the dismantling of social safety nets, which he sees as essential factors driving incarceration rates across racial groups (Source).

These critiques suggest that while The New Jim Crow has been instrumental in drawing attention to racial inequities, further research and analysis may be necessary to fully understand the complex causes and dynamics of mass incarceration, including class, community interests, and public health factors.

OPTIONAL: The 13th (Dir. Ava Durvernay, 2016)

The film provides an insightful overview of how the 13th Amendment’s exception clause allowed racial control to continue under the guise of criminal punishment, linking directly to Michelle Alexander’s arguments in The New Jim Crow about how mass incarceration serves as a modern system of racial oppression. Watching 13th can deepen understanding of these themes but is not required.

Conclusion

Social order depends on a delicate balance between encouraging conformity and tolerating deviance. From Durkheim’s view of deviance as a catalyst for social cohesion to Becker’s insight into the power of labeling, sociological theories remind us that deviance is not merely a matter of individual choice but a reflection of societal norms, values, and power structures. Institutions, sanctions, and public perceptions all play a role in defining and managing deviant behavior, shaping the boundaries of social life.

By examining issues like mass incarceration and Broken Windows policing, it becomes clear that societal responses to deviance often reinforce existing inequalities. Understanding these dynamics challenges us to think critically about the systems we uphold and the values they reflect. As societies evolve, grappling with the complexities of deviance and conformity offers opportunities to create more just and inclusive frameworks for maintaining social order.

Key Concepts

Anomie: A state of normlessness that occurs when society’s expectations and values break down, often during periods of rapid change. In such times, people may feel disconnected and unsure of acceptable behaviors.

- Example: During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people felt uncertain about social norms, leading to confusion about acceptable interactions.

Broken Windows Theory: A theory suggesting that visible signs of disorder, such as broken windows or graffiti, encourage further crime by signaling neglect. Addressing minor offenses can help prevent more serious crimes by creating a sense of order.

- Example: New York City officials removed graffiti from subway cars in the 1980s to discourage further vandalism and reduce crime throughout the subway system.

Conformity: The influence exerted by a group that leads individuals to change their beliefs or behaviors to align with group norms, helping maintain social order. Social institutions promote conformity through socialization.

- Example: Students follow school rules to succeed academically, and individuals obey laws to avoid punishment.

Crime: A behavior deemed unlawful by a society’s legal framework. Crimes vary across time and place, reflecting the values and structures of a given society.

- Example: Prohibition criminalized alcohol in the U.S. in the 1920s, whereas today it is widely legal, showing how crime is socially defined.

Criminal Justice System: The network of institutions that enforce laws, deliver justice, and manage punishment. It includes law enforcement, courts, and correctional facilities, aimed at maintaining social order and protecting citizens.

- Example: Police, court systems, and prisons work together to process and detain individuals accused of crimes.

Criminalization: The process by which certain behaviors or groups are seen as inherently criminal, often influenced by biases and power dynamics. This process can lead to targeted laws and enforcement practices.

- Example: Drug laws in the U.S. have disproportionately targeted Black and Latino communities, resulting in higher arrest rates despite similar rates of drug use among racial groups.

Deviance: Behaviors or actions that violate social norms. Deviance is context-dependent; what is considered deviant varies across cultures and over time. Deviance can be but doesn’t have to be illegal.

- Example: Chewing with one’s mouth open may be seen as deviant in some cultures but is not illegal.

Formal Sanction: An official reward or punishment imposed by recognized authorities or institutions to enforce rules or laws.

- Example: Imprisonment for a crime is a formal negative sanction, while a job promotion is a formal positive sanction.

In-Group: A social group an individual identifies with and sees as essential to their identity, creating feelings of loyalty and solidarity.

- Example: A person who strongly identifies with their nationality may feel pride and connection with others from the same country.

Informal Sanction: Unofficial reactions to behavior that reinforce social norms, occurring in everyday interactions rather than through formal authorities.

- Example: A smile or compliment for kindness is an informal positive sanction, while a disapproving look is an informal negative sanction.

Labeling: The process of defining certain people or behaviors as deviant, which can lead to societal stigmatization and affect an individual’s self-concept.

- Example: Someone repeatedly labeled as a “troublemaker” in school may internalize the label, affecting their behavior and interactions.

Law: A system of rules established by society to regulate behavior, provide order, and protect citizens. Laws are enforced by government institutions and carry formal consequences.

- Example: Laws against theft are designed to protect property and deter harmful actions.

Mass Incarceration: The large-scale imprisonment of individuals, often resulting from policies that target specific communities, especially marginalized groups.

- Example: During the 1980s there was a massive increase in the Unite States prison population. Many scholars attribute this to the War on Drugs, which disproportionately affected Black and Latino male populations.

Negative Sanction: A punishment or negative response aimed at discouraging certain behaviors that deviate from social norms.

- Example: A fine for littering is a negative sanction meant to discourage behavior that harms the environment.

Out-Group: A group that an individual does not identify with and may view as fundamentally different or opposed to their in-group.

- Example: Someone with a strong religious affiliation may see members of other faiths as part of an out-group, which can lead to feelings of rivalry.

Positive Sanction: A reward or positive reaction intended to encourage desirable behavior, reinforcing social norms.

- Example: A student receiving a scholarship for academic excellence is a positive sanction encouraging high achievement.

Primary Deviance: Minor or occasional acts of rule-breaking that don’t result in a deviant identity or significant societal reaction.

- Example: A young person shoplifting once without developing a reputation as a “criminal.”

Secondary Deviance: Repeated deviant behavior that begins to shape an individual’s self-identity, often as a result of societal labeling.

- Example: A person repeatedly caught shoplifting who is labeled a “thief” may internalize this label, leading to further deviant behavior.

Social Control: Mechanisms, strategies, and institutions used by society to regulate behavior and maintain conformity to norms and laws.

- Example: Legal penalties for theft (formal control) or family disapproval for skipping school (informal control) help guide behavior.

Social Power: The ability to influence or control the behavior of others, often held by certain individuals, groups, or institutions within a society.

- Example: Governments hold social power to enforce laws, while influential individuals or organizations can shape public opinion.

Reflection Questions

- How does structural-functionalism, as developed by Emile Durkheim, explain the role of deviance in maintaining social order, and what are some examples where rule-breaking reinforces shared values?

- According to conflict theorists like Karl Marx and modern critics like Michelle Alexander, how does the criminal legal system reinforce social inequality through the selective enforcement of laws?

- What does the Broken Windows Theory suggest about how minor disorder leads to more serious deviance, and how might critics respond to this approach in terms of fairness or effectiveness?

- How can deviance be a force for positive change, and what are some examples where breaking the rules led to greater justice or progress?