Table of Contents

- Learning Objectives

- Introduction

- The Economic Institution

- Capitalism as the Modern Economic Institution

- The Rise of Industrial Capitalism

- Explaining Capitalism Today: The Shift From Fordism to Neoliberalism

- Conclusion

- Key Concepts

- Reflection Questions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, students will be able to:

- Define the economic institution from a sociological perspective and explain how it organizes production, distribution, consumption, and markets within society.

- Describe the key components of the economic institution, including how they function historically and globally across different social systems.

- Analyze the rise of capitalism as a historical system, including the contributions of thinkers such as Paul Sweezy, Robert Brenner, and Immanuel Wallerstein.

- Explain the transformation from feudalism to capitalism, emphasizing the long sixteenth century, global trade, and the emergence of wage labor.

- Evaluate the development of industrial capitalism, including its impact on labor, urbanization, colonialism, and global inequality.

- Compare and contrast economic regimes within capitalism, specifically Fordism and neoliberalism, and assess their effects on production, labor, consumption, and state intervention.

- Critically assess the consequences of neoliberalism, including rising inequality, environmental degradation, and weakening democratic institutions.

- Apply sociological theories to contemporary critiques of capitalism, drawing on thinkers such as Naomi Klein, Wendy Brown, Slavoj Žižek, and Immanuel Wallerstein.

- Interpret capitalism not as a fixed or natural system, but as a historical structure shaped by power, values, and institutional choices.

- Reflect on future possibilities beyond neoliberalism, analyzing current challenges and debates around equity, sustainability, and the role of government in the economy.

Introduction

Imagine going to the store to buy groceries. Behind this seemingly simple act lies a vast network of systems determining how the food is grown, transported, priced, and made available to you. These systems, which influence nearly every aspect of daily life, are part of what sociologists call the economic institution. But how much do we really understand about this fundamental structure of society? What historical forces shaped it, and how does it impact the way we live today?

To answer these questions, we need to move beyond the surface of terms like “economy” or “capitalism” and explore their deeper sociological meanings. The economy is not just about money or markets; it is a social institution shaped by relationships, norms, and values that organize how societies meet their material needs. This chapter will examine how the economic institution evolved over time, focusing on its key components—production, distribution, consumption, and markets—and their profound influence on human life. By examining the rise of capitalism as a historical system, we will uncover how this way of organizing resources transformed societies and continues to shape our world today.

This chapter traces the economic institution’s development, beginning with its foundations in early societies and moving through the transformative periods of the long sixteenth century and the Industrial Revolution. We will explore how capitalism emerged as a dominant system, reshaping labor, society, and global relationships. Additionally, we will consider the evolution of capitalism from Fordism—characterized by mass production and stable wages—to neoliberalism, which prioritizes free markets and limited government intervention. Finally, we will examine the challenges of today’s economic systems and the possible futures that lie ahead.

Understanding the economic institution from a historical sociological perspective helps us see how deeply it shapes our daily lives. By connecting historical shifts to modern realities, this chapter will encourage you to think critically about the systems that impact everything from the jobs you pursue to the products you buy. This journey through history and sociology offers tools to better understand and navigate the complex economic world we live in.

The Economic Institution

The term economy commonly appears in discussions on topics ranging from job reports and stock markets to the cost of everyday essentials like gas and groceries. Media personalities interpret it through trends in employment and inflation, politicians debate its impact on policy, and economists study it using tools like GDP and spending patterns. For most people, the economy is experienced in everyday life as the cost of living or the ability to afford necessary goods and services.

Despite its frequent mention, the concept of the economy is rarely explored beyond surface-level indicators. This module approaches the economy from a sociological perspective, examining it not only as a set of financial statistics but as a social institution. Sociologists view the economy as a network of relationships and structures that organize production, distribution, and consumption within society.

Here we focus on historical sociology, which studies how societies and institutions develop and change over time. Through this lens, we will explore how the economic institution has evolved, particularly with the rise of capitalism, and how it has influenced society across different periods and cultures.

Defining the Economic Institution

In sociology, the economic institution is understood as more than just financial transactions or markets. At its core, the economic institution is a system of organized activities and relationships surrounding the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services within a society. It involves a network of norms, values, and practices that shape how people acquire essentials like food, housing, and technology.

Rather than viewing the economy solely as a series of transactions, sociologists consider it a foundational structure that influences how societies allocate resources and establish social roles. The economic institution exists alongside other key social institutions, such as family, government, and education, each governing a different area of human interaction and need.

Whether in a small, local community or a global economy, the economic institution serves a vital role in shaping society. Through different historical and cultural contexts, it adapts to meet changing needs while maintaining its primary function of organizing resources and social relationships.

Key Components of the Economic Institution

The economic institution is made up of interconnected components that organize how societies meet their material needs. These components are as follows:

- Production: Production” means making goods or providing services that people need or want. This can involve farming, building, or creating things like technology. Throughout history, societies have produced goods in different ways: some relied on farming communities to grow food, while modern societies often use factories and technology to make everything from clothing to smartphones. Production is how we get the items we rely on every day.

- Distribution: Distribution” is how these goods and services get to the people who need them. This involves both physically moving items—like transporting food from farms to stores—and deciding who can access them. In some societies, goods are shared based on status, while in others, they’re available to those who can pay for them. Distribution shapes who can afford what and reflects how resources are shared in society.

- Consumption: Consumption” is the act of using or buying goods and services to meet our needs and wants. It’s not just about buying things; consumption reflects cultural values and personal identity. For instance, people might buy luxury items to show success or essentials like groceries to support their family. Different societies view consumption differently—some value minimalism, while others see consumer goods as signs of status or lifestyle.

- Markets: Places, either physical or online, where people buy and sell goods and services. Markets range from local farmer’s markets to global online platforms. They’re guided by supply and demand, meaning prices often depend on how much of something is available and how many people want it. Over time, markets have evolved from simple barter systems to complex, digital exchanges that connect buyers and sellers around the world. Markets are essential because they help determine how resources are shared and who can access them.

Together, these components reveal the economic institution as a complex and adaptive structure that shapes societies’ ways of living, influencing how people interact, fulfill their needs, and view their roles in a larger social world.

The Economic Institution Across Time and Space

The economy isn’t just a modern invention—it has existed in different forms across history and in many societies. From ancient civilizations to today’s globalized world, economies have always been about organizing the production, distribution, and consumption of goods.

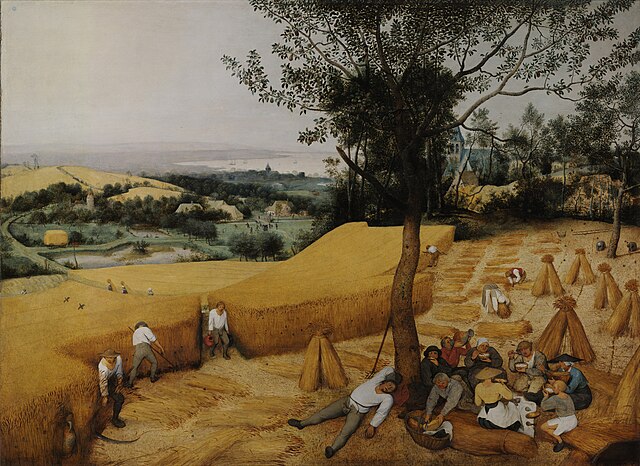

For example, ancient societies like Mesopotamia and Egypt had their own economic systems, which included trade routes, farming, and rules about who got what resources. These economies were structured differently than what we see today but still focused on production, distribution, consumption, and markets to keep their societies running.

Fast forward to the Industrial Revolution, and economies changed dramatically. In the 18th and 19th centuries, new machines allowed goods to be made faster in factories, which transformed society. People moved from rural areas to cities to work in these factories, changing where people lived and how they earned a living. This period also saw the start of mass consumption, as more goods became available to more people.

Today, technology continues to reshape the economy in even more complex ways. Production is automated, goods are shipped globally, and markets are often online. But despite these changes, the main parts of the economic institution—production, distribution, consumption, and markets—still serve the same basic purpose: helping societies meet their needs.

Capitalism as the Modern Economic Institution

“It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.”

This quote, often attributed to thinkers like Slavoj Žižek and Fredric Jameson, captures how deeply embedded capitalism is in our daily lives in that we can’t imagine life without it.

Capitalism is a unique way of organizing the economy, focused on private ownership and making a profit. In a capitalist system, resources like land, labor, and capital (money for investment) are privately owned and used to produce goods and services that are sold in markets. People earn money by working for wages, which they then use to buy the things they need and want. This cycle of working, earning, and spending is central to capitalism and helps keep the economy going.

One main feature of capitalism is wage labor, where people work for businesses in exchange for a paycheck. In earlier systems, many people worked directly to meet their own needs, like growing their own food. But in capitalism, people rely on wages to buy the things they need, creating a system where work and consumption go hand in hand.

Capitalism also emphasizes continuous growth, where companies aim to produce and sell more over time. Markets play a major role, as competition between businesses helps set prices and drives innovation. This constant push for profit and growth influences not just what we buy, but how we live and work.

As a social institution, capitalism affects nearly every aspect of life, from the ways people interact to the types of jobs and products that are available. By understanding capitalism as more than just an economic system, we can see how deeply it shapes our society and influences our relationships, values, and global connections.

Capitalism as a Historical System

To fully understand capitalism, it helps to think of it as a historical system—an economic and social structure that has evolved over time in response to major changes in society, technology, and culture. Unlike simpler systems that may only last a few years, a historical system like capitalism has shaped lives for centuries and has changed as societies have developed.

Importantly, as a historical system, capitalism had a starting point and could, in theory, have an endpoint. It began under specific conditions and evolved into the global system we know today.

The Rise of Capitalism in the Long 16th Century

The period often called the “long 16th century,” from around 1450 to 1640, is seen as the beginning of modern capitalism. During this time, Europe experienced significant changes: trade expanded across continents, cities grew, and a new social class of merchants and traders began gaining influence. This shift marked a move away from feudalism—a system where land was controlled by nobles and worked by peasants—to a market-based economy focused on growth and profit.

Global trade routes were essential to this shift, especially those connecting Europe with Asia, Africa, and the Americas. These trade routes allowed European merchants to access valuable resources like spices, gold, and textiles, which they could sell for high profits. This influx of wealth also led to financial innovations, such as banks and stock exchanges, which allowed people to invest more into trade and production. These changes helped capitalism grow from a local to an international system.

Why Did Capitalism Arise?

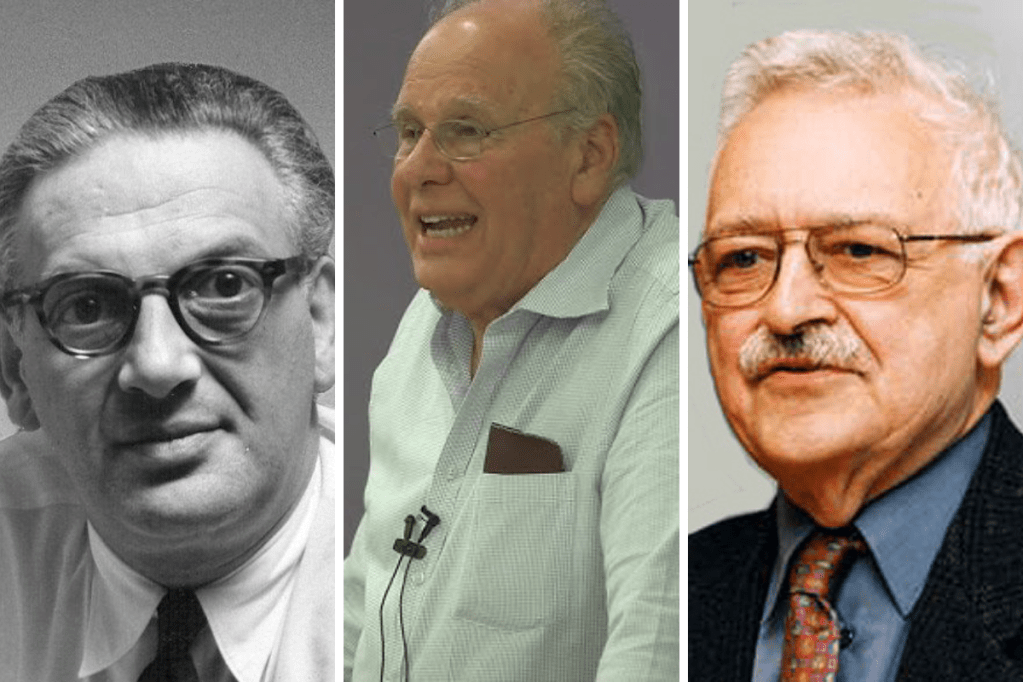

The rise of capitalism didn’t happen overnight, and there are different ideas about what caused it. Three thinkers—Paul Sweezy, Robert Brenner, and Immanuel Wallerstein—each had a unique view on why feudalism gave way to capitalism.

- Paul Sweezy believed that the growth of trade and cities weakened the old feudal system. As towns expanded and trade routes connected new places, merchants gained power. This shift toward markets and profits eventually replaced the feudal obligations that had previously structured the economy.

- Robert Brenner looked at how rural life changed after the Black Death, a plague that wiped out a large part of Europe’s population in the 1300s. With fewer workers available, peasants were able to push for better conditions. But over time, landowners in Western Europe wanted to make more money from their land, which led them to push peasants off the land or make them pay rent. This created a group of people who needed to work for wages, helping to establish a wage-based economy.

- Immanuel Wallerstein saw capitalism as a global transformation. He argued that as Western Europe’s markets grew, Eastern Europe started producing large amounts of agricultural goods for export to Western Europe. This shift was reinforced by advancements in navigation and the growth of international trade routes, especially with the Americas. The Americas provided new resources and labor, creating an international division of labor that enriched Western Europe while linking other regions, including Eastern Europe, as key suppliers. This global network laid the foundation for the capitalist world economy.

These different ideas show that capitalism likely emerged from a mix of expanding trade, social changes after the Black Death, and a global network of production and trade. Together, these forces helped lead to a decline in feudalism and create the economic system we know as capitalism today.

The Rise of Industrial Capitalism

The rise of industrial capitalism marked a major shift in both the economy and society. Starting in the late 1700s and accelerating throughout the 1800s, the Industrial Revolution introduced new machines, large factories, and wage labor on a large scale. This transformation reshaped capitalism by centralizing production in factories, where goods could be made quickly and in huge quantities, creating the foundation for the global economy we know today.

The Rise of Industrial Capitalism: How It Transformed the Modern World

Industrial capitalism brought about a new way of producing goods. Factories became the heart of the economy, using machines that could make products much faster than traditional, handmade methods. Instead of small, local workshops, industrial capitalism relied on mass production, where factories produced everything from textiles to steel at record speed. For example, by the early 1800s, Britain had over 3,000 textile mills—a huge increase from just a few a century earlier (Source).

This shift to factory production also led to rapid urbanization, as people moved to cities to work in the new industrial economy. In England, only about 20 percent of people lived in cities in 1800, but by 1850, that number had risen to nearly 50 percent. Cities like Manchester, Liverpool, and Birmingham grew quickly as factory jobs attracted workers from rural areas (Source). For instance, Manchester’s population jumped from about 90,000 in 1801 to over 300,000 by 1851 (Source). This migration created large urban centers that shaped modern life and marked a turning point in how people lived and worked.

Capitalism Goes Global

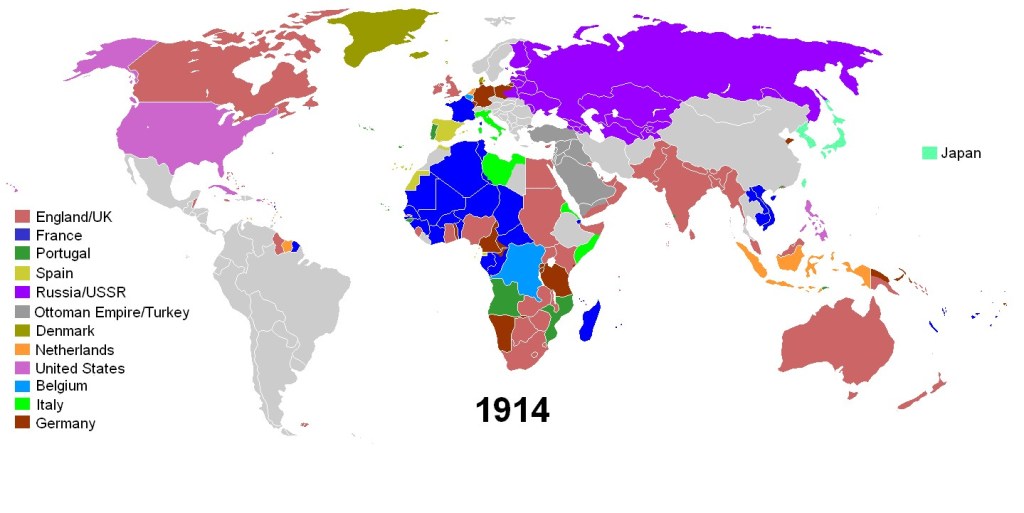

Industrial capitalism quickly spread beyond Europe and North America through colonialism. Colonialism is when a powerful country takes control of a foreign land to use its resources and influence its politics, economy, and culture. As factories needed more raw materials like cotton, coal, and iron, industrialized countries looked to other parts of the world for supplies and new markets to sell their goods. European powers, especially, expanded their empires into Africa, Asia, and the Americas to secure these resources and control labor.

By 1914, Britain’s colonial empire alone covered about 25 percent of the world’s land and governed around 400 million people (Source). Colonies not only provided raw materials but also served as guaranteed markets for mass-produced goods from Europe. This global reach of capitalism led to a system where wealth and industrial power were concentrated in Europe and North America, while colonies provided raw materials and cheap labor. These unequal relationships created patterns of wealth and poverty that still influence global economic inequalities today.

Transforming Labor and Society

Industrial capitalism didn’t just change economies—it also transformed work and society. In factories, workers faced long hours, low pay, and unsafe conditions, often starting at young ages. For example, in 19th-century England, textile workers, including women and children, typically worked 12- to 16-hour days in poorly ventilated spaces (Source). Outside of factories, industrial capitalism also depended on enslaved and indentured labor to supply essential resources. Enslaved people on American plantations produced cotton for European mills, while indentured laborers from India and China (often called coolies) worked on plantations, railroads, and mines in colonies, often under harsh conditions.

As industrial nations competed globally, colonial expansion, such as the Scramble for Africa, allowed European countries to secure materials needed for industrial growth. However, this economic power also created deep inequalities, causing poverty and dependency in colonized areas. These harsh conditions led to widespread discontent, sparking labor unions, socialist movements, and anti-colonial uprisings worldwide. Over time, these movements helped establish labor laws, social welfare programs, and modern labor rights that aimed to protect workers and address inequalities in capitalist systems.

The Legacy of Industrial Capitalism

Industrial capitalism dramatically changed both society and the global economy, building on shifts that began in the long sixteenth century, when global trade routes, new social classes, and market-driven economies first took shape. What started as local trade and small-scale production evolved over time into a system powered by factories, global markets, and wage labor. This transition brought new wealth and technological advances, but it also led to deep inequalities, harsh working conditions, and environmental damage.

By the early 20th century, industrial capitalism had transformed societies and reinforced patterns of wealth and power that remain today. Its impact is still seen in debates on fair labor practices, economic justice, and sustainability, showing how the early foundations of capitalism continue to shape our world.

Explaining Capitalism Today: The Shift From Fordism to Neoliberalism

In capitalism, an economic regime is a set of production, labor, and consumption practices that define a certain period. Each regime fits within capitalism’s broader system of private ownership and market-driven growth, but it creates unique relationships between businesses, workers, and consumers.

In the post-World War II era, two major regimes shaped capitalism: Fordism and neoliberalism. Fordism, which dominated after World War II, emphasized mass production, stable wages, and strong government support for workers. Later, neoliberalism emerged as the new economic regime, focusing on free markets, reduced government intervention, and flexible labor. This shift changed global capitalism, influencing economic policies, work conditions, and social structures.

Fordism: The Foundation of Post-World War II Capitalism

Fordism, named after automaker Henry Ford, refers to a system of mass production and mass consumption that helped drive economic growth in many Western countries after World War II. Fordism is based on three main principles: standardized production, well-paid workers, and government support for economic stability.

- Standardized Production and Assembly Lines: Fordism introduced standardized production, where identical products are made in large quantities using assembly lines. Henry Ford pioneered this method in the early 20th century to make cars affordable for ordinary people. In an assembly line, each worker performs one repetitive task, speeding up production and keeping costs low. This model spread beyond cars and became a way to quickly and efficiently produce many goods. By 1955, the United States was producing 7 million cars a year, compared to fewer than 2 million annually in the early 1940s, showing the widespread impact of Fordist production (Source).

- Well-Paid Workers and Mass Consumption: Fordism also believed in paying workers enough so they could afford to buy the goods they helped make. Ford’s workers earned a decent wage, which gave them the income to buy products like cars, homes, and appliances. This created a cycle where higher wages led to more spending, which then boosted the economy. During the 1950s, union membership in the United States reached nearly 35% of the workforce, helping workers secure good wages and benefits and supporting the growth of a strong middle class (Source).

- Government Support and the Welfare State: Fordism thrived under what is known as the welfare state, where governments actively supported economic stability and protected workers. This included social safety nets like Social Security, unemployment benefits, and healthcare programs. These supports reduced financial risks for workers, giving them stability even if they lost their jobs or needed medical care. Social programs like Medicare and Social Security in the U.S. provided financial security for millions, contributing to the stability of the Fordist system.

After World War II, Fordism became the dominant economic model in the United States and other Western nations. The combination of mass production, good wages, and government support fueled steady economic growth. This created a society where people had stable jobs, could afford to buy products, and benefited from government programs, leading to a strong and stable economy.

The Decline of Fordism

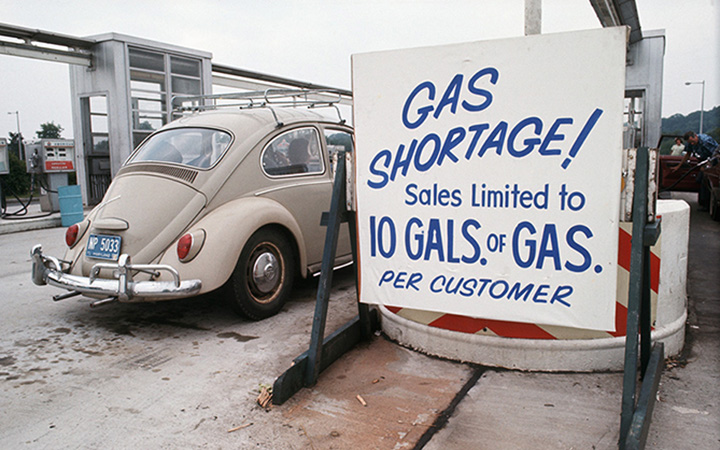

While Fordism brought decades of economic growth and stability after World War II, it began to face serious challenges by the 1970s. Economic changes and global competition made it difficult for the Fordist system, which relied on mass production, stable jobs, and government support, to keep up. Major issues like economic stagnation, new global competitors, and changing consumer preferences highlighted the limits of Fordism’s traditional methods.

- Economic Stagnation and Stagflation: In the 1970s, stagflation—a mix of slow economic growth, high inflation, and rising unemployment—put pressure on Fordism. Inflation rates in the U.S. spiked to over 13% by 1980, while unemployment reached nearly 11% by 1982 (Source). At the same time, oil prices soared due to oil crises in 1973 and 1979, raising energy costs for Fordist industries that relied on affordable fuel (Source). These factors weakened consumer demand, making mass production and mass consumption harder to sustain.

- Global Competition and Outsourcing: Increasing competition from other countries, especially Japan, also strained Fordism. Japanese companies used lean production techniques, which allowed them to make high-quality, fuel-efficient products at lower costs. This pressured American and European companies to cut costs, and many responded by moving production to countries with cheaper labor. Between 1979 and 1989, the U.S. lost nearly 1.5 million manufacturing jobs to outsourcing, which reduced the stable, well-paid jobs that had supported the Fordist economy (Source).

- Demand for Flexibility and Customization: Consumer preferences began to shift away from standardized products toward more variety and customization. Industries like electronics and technology needed flexible production systems to respond quickly to new trends and shorter product cycles. The Fordist model, with its rigid production lines, couldn’t keep up with this demand for flexibility. As a result, companies began moving toward more adaptable production models, marking a shift from Fordism to a post-Fordist economy.

The Rise of Neoliberalism

After the economic challenges of the 1970s, including the decline of Fordism, Western governments and economies began to adopt a new philosophy called neoliberalism. Emerging in the 1980s, neoliberalism promoted market-driven policies as a way to solve economic issues like stagnation and global competition. While Fordism had relied on government intervention and stable jobs, neoliberalism redefined the role of the government and businesses, leading to major changes in capitalism.

Neoliberalism’s Characteristics

Neoliberalism is an economic and political approach that emphasizes free markets, private ownership, and minimal government involvement in the economy. It marked a significant shift from the welfare-state policies of Fordism, focusing more on individual responsibility and the efficiency of private businesses rather than public welfare programs. Key leaders like Margaret Thatcher in the U.K. and Ronald Reagan in the U.S. promoted neoliberal policies, which reshaped economies and governments in Western countries and beyond (Source).

Neoliberalism is defined by several main ideas:

- Market Deregulation: Market Deregulation: Neoliberalism promotes the idea that markets work best with little government interference, which calls for degregulation. Deregulation is when governments reduce rules and regulations on businesses, aiming to increase competition, efficiency, and economic growth. In the U.S., for example, deregulation in the financial sector during the 1980s and 1990s led to rapid growth but also created risks, as looser banking rules allowed for new, riskier financial products (Source).

- Privatization of Public Services: Neoliberalism encourages transferring public services to private ownership. This includes areas like healthcare, education, utilities, and transportation. Privatization is seen as a way to make these services more efficient by exposing them to competition. For instance, under Thatcher’s leadership, the U.K. privatized industries like British Telecom and British Gas, aiming for short-term gains and budget savings (Source). However, privatization often led to reduced access to services and higher costs for consumers.

- Labor Flexibility and Reduced Worker Protections: Neoliberalism promotes flexible labor, including part-time, temporary, and freelance work over traditional full-time roles. This flexibility helps businesses adjust to changing market demands, but it has also led to job insecurity for workers. Many part-time or freelance workers lack benefits like health insurance and paid leave. Labor unions, once powerful under Fordism, lost influence as governments passed policies that weakened workers’ ability to negotiate for better wages and conditions.

- Emphasis on Individual Responsibility: Neoliberalism shifts welfare responsibilities from the government to individuals. People are expected to manage their own economic success and well-being with less government support. For example, rather than relying on public healthcare, people are encouraged to buy private insurance. This approach is based on the belief that personal responsibility and hard work lead to success, although critics argue that it overlooks barriers faced by disadvantaged groups.

- Globalization and Financialization: Neoliberalism has fueled globalization, encouraging companies to expand internationally to reduce costs and increase profits. This led to global supply chains, where production is often outsourced to countries with lower labor costs. Financialization, or the growing influence of financial markets, also became central under neoliberalism, with companies focusing on short-term profits for investors. This focus on finance often comes at the expense of long-term growth, worker well-being, or product quality.

The Decline of Neoliberalism and Prospects for the Future

While neoliberalism initially helped address economic challenges after Fordism, its downsides have become more noticeable in recent years. Critics argue that neoliberal policies have led to greater inequality, environmental damage, economic insecurity, and even a decline in traditional social values. These criticisms from both progressive and conservative sides suggest that neoliberalism may be reaching its limits, paving the way for a new economic approach.

- Rising Inequality and Economic Insecurity: Neoliberalism’s focus on free markets and reduced worker protections has led to greater income inequality and economic insecurity. Economist Thomas Piketty argues that wealth inequality is a natural result of capitalism, especially under neoliberal policies that prioritize profits. Today, the top 1% of earners in the U.S. hold over 40% of total wealth, compared to about 25% in the 1970s. This wealth gap has left many workers struggling financially, with stagnant wages and rising living costs (Source).

- Environmental Concerns: Neoliberalism’s emphasis on short-term profits and deregulation has led to unsustainable resource use and environmental harm. Scholar Naomi Klein argues that neoliberal policies conflict with environmental sustainability. Since 1980, global CO₂ emissions have nearly doubled as industrial output and deregulated markets accelerated pollution and resource depletion. Klein contends that addressing climate change requires rethinking neoliberalism’s focus on unrestricted economic growth (Source).

- Political Instability and Public Discontent: Economic inequality and job insecurity under neoliberalism have fueled political divisions and anti-establishment movements. Political theorist Wendy Brown argues that neoliberalism weakens democracy by treating people as consumers instead of citizens with a shared public life (Source). This emphasis on individualism has eroded social cohesion and weakened collective institutions, contributing to the rise of populist movements worldwide. Surveys by Pew Research Center show that trust in government has dropped, with only about 20% of Americans reporting trust today, compared to around 70% in the 1960s.

- Erosion of Traditional Values and Community: Some conservative thinkers, like Patrick Deneen, argue that neoliberalism’s focus on individual success weakens commitments to family, faith, and community. For example, the pressure for dual incomes and economic demands has left less time for religious and community involvement, with U.S. church membership dropping below 50% in recent years, compared to over 70% in the 1970s. Deneen suggests that this focus on personal gain over community well-being undermines social stability (Source).

- The COVID-19 Pandemic and a Push for Change: The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted weaknesses in neoliberal systems, exposing gaps in healthcare, employment, and social safety nets. Political economist Mariana Mazzucato argues that the pandemic shows the need for stronger public infrastructure and greater government involvement in essential services. She advocates for a “mission-oriented” approach, where governments proactively address social challenges, invest in innovation, and promote sustainable development (Source).

Toward a New Economic Regime?

The decline of neoliberalism has brought us to a crossroads, a moment that sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein describes as utopistics: a time when society imagines and pursues different futures to replace a failing system. As neoliberalism’s limitations become more visible, societies are debating two main paths: one that promotes equality, justice, and democracy, and another that leans toward authoritarianism and centralized control.

On one side, there is hope for a more equal and democratic society, supported by movements pushing for social justice, climate action, and more public participation in government. Across the globe, calls for fairer wages, workers’ rights, and environmental policies—like the European Green Deal and the U.S. Green New Deal—reflect a desire for a sustainable, fair economy that prioritizes people and the planet. Such movements aim to create a society that values justice, inclusivity, and individual well-being over profit.

On the other side, the instability caused by neoliberalism has also led some to support authoritarianism. In countries like Russia and China, strong central governments have prioritized stability and control, often limiting freedoms like press and privacy to maintain order (Source). Even in democratic nations, like the United States, concerns about privacy, surveillance, and limits on voting rights are growing, reflecting fears that democratic institutions may be weakening as central power increases.

This moment in history presents both opportunities and risks. Societies face a choice: a future that embraces greater equality and democracy or one that turns toward centralized power and control. Wallerstein’s idea of utopistics reminds us to consider these possible futures carefully. The direction we take will likely depend on grassroots movements, policy choices, and global cooperation to address the big challenges of our time.

Conclusion

The economic institution is far more than an abstract concept; it is a dynamic force that has shaped societies across time. From the early trade networks of ancient civilizations to the rise of capitalism and its transformation through industrialization, Fordism, and neoliberalism, this institution has evolved alongside humanity. Each transformation has brought profound benefits, such as technological advancements and economic growth, but also significant challenges, including inequality, environmental harm, and shifting social values.

By viewing the economy as a social institution, we see it as a product of human decisions and relationships rather than a natural or fixed system. This perspective highlights both its adaptability and its capacity for change. As neoliberalism faces growing criticism and calls for reform, society stands at a crossroads. Will the future bring systems that prioritize equity, sustainability, and collective well-being, or will it deepen existing inequalities and social divides? The choices we make today will shape not only the economy but also the social structures and values of future generations.

Key Concepts

Assembly Lines: A manufacturing process in which a product is assembled in a step-by-step sequence by workers or machines at various stations.

- Example: Henry Ford introduced assembly lines in the early 20th century to produce automobiles more efficiently.

Capitalism: An economic system in which private individuals or corporations own and operate the means of production and distribution of goods and services, aiming for profit.

- Example: The United States operates under a capitalist system, where most industries are privately owned.

Colonialism: The practice by which a country establishes control over foreign territories, often to exploit resources and impose its political and cultural systems.

- Example: Britain’s colonization of India involved control over local governance and extraction of resources like spices and cotton.

Consumption: The act of using goods and services to satisfy needs or wants.

- Example: Buying a new smartphone is an example of consumer consumption.

Coolies: Contracted laborers, often from Asia, brought to work on plantations or in mines under harsh conditions, resembling forced labor.

- Example: Coolie labor was used on sugar plantations in the Caribbean after the abolition of slavery.

Deregulation: The reduction or elimination of government controls over an industry, often to increase competition and efficiency.

- Example: The U.S. airline industry was deregulated in the 1970s, which led to lower prices and more flights.

Distribution: The process by which goods and services are allocated and made accessible to consumers.

- Example: A food distribution network moves produce from farms to grocery stores.

Economic Institution: The organized structures and norms governing production, distribution, and consumption in a society.

- Example: In a market economy, private companies and consumers operate within the economic institution.

Economic Regime: A system governing economic policies and practices within a certain time period, often driven by specific principles.

- Example: Fordism was the dominant economic regime in the post-World War II era.

Economy: The system of production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services within a society.

- Example: A strong economy usually indicates high employment and stable prices.

Factory System: A system of manufacturing that emerged during the Industrial Revolution, characterized by mass production in centralized locations.

- Example: Textile mills in 19th-century England are classic examples of the factory system.

Feudalism: A medieval economic and social system in which land was owned by nobles and worked by peasants in exchange for protection.

- Example: In feudal Europe, peasants worked land owned by a lord in return for shelter and security.

Financialization: The process by which financial markets, institutions, and motives become increasingly important in economic systems.

- Example: The rise of stock trading and financial services in the U.S. in recent decades reflects financialization.

Fordism: A system of mass production and consumption based on standardized goods and high wages for workers, named after Henry Ford.

- Example: Post-World War II America saw widespread use of Fordist principles in manufacturing and labor.

Globalization: The increasing interconnectedness of economies, cultures, and populations across the world.

- Example: The spread of technology companies like Apple and Samsung worldwide is a sign of globalization.

Historical Sociology: The study of social systems and institutions over time to understand their development and impact on societies.

- Example: A historical sociologist might study the rise and fall of feudalism in medieval Europe.

Historical System: A concept of social organization that evolves over time and eventually comes to an end.

- Example: Feudalism is considered a historical system that transitioned into capitalism.

Industrial Revolution: The period of rapid industrialization from the late 18th to early 19th centuries, which transformed production methods and social structures.

- Example: The invention of the steam engine was a major innovation during the Industrial Revolution.

Labor Flexibility: The ability of an employer to adjust labor practices to meet market demands, often involving temporary or part-time work.

- Example: Gig economy platforms like Uber and TaskRabbit reflect labor flexibility in modern economies.

Long Sixteenth Century: The period from approximately 1450 to 1640, marking the transition from feudalism to early capitalism in Europe.

- Example: The expansion of European trade with Asia and the Americas took place during the Long Sixteenth Century.

Markets: Platforms where goods and services are bought and sold, with prices often determined by supply and demand.

- Example: Stock markets allow people to buy and sell shares of companies.

Neoliberalism: An economic philosophy emphasizing free markets, privatization, and minimal government intervention in the economy.

- Example: In the 1980s, policies in the U.K. and the U.S. shifted toward neoliberalism under leaders like Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan.

Privatization: The transfer of public services or assets to private ownership, often with the aim of increasing efficiency.

- Example: The privatization of British Rail in the 1990s turned the public railway system over to private companies.

Production: The process of creating goods and services to meet consumer needs and wants.

- Example: The production of automobiles in factories involves labor, materials, and machinery.

Stagflation: An economic condition of stagnant growth combined with high inflation and unemployment.

- Example: The U.S. experienced stagflation during the 1970s, partly due to oil crises.

Utopistics: A term by Immanuel Wallerstein describing the study of possible, radically different social systems in response to current issues.

- Example: Utopistics encourages imagining systems beyond capitalism and neoliberalism in response to social inequalities.

Wage Labor: A system in which individuals sell their labor for wages to earn a living, often within capitalist economies.

- Example: Most employees in the U.S. work as wage laborers, earning pay based on hours worked or tasks completed.

Welfare State A system in which the government provides social services like healthcare, education, and unemployment benefits to support citizens’ well-being.

- Example: Sweden has a robust welfare state, offering free healthcare and extensive social benefits.

Reflection Questions

- The reading argues that capitalism should be viewed as a social institution. How does this perspective shift the way we understand everyday decisions like shopping, working, or managing money?

- How did colonialism help establish global economic inequalities, and what examples from the reading show how those inequalities continue to shape labor and trade today?

- The reading contrasts Fordism’s emphasis on stability with neoliberalism’s focus on flexibility and markets. How have these two systems shaped opportunities and challenges for workers across different time periods?

- Immanuel Wallerstein, Robert Brenner, and Paul Sweezy each offer different theories about how capitalism developed. What are the key points of disagreement between them, and why does the debate matter?