Table of Contents

- Learning Objectives

- Introduction

- Social Stratification

- Class Stratification and the Challenges of Social Mobility

- Social Mobility: The Fluidity of Class Boundaries

- Debating Poverty: Three Sociological Views

- Conclusion

- Key Concepts

- Reflection Questions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, students will be able to:

- Define social stratification and explain how structured systems of inequality operate across historical and contemporary societies.

- Differentiate between closed and open systems of stratification, including caste, feudal, and class-based systems, and assess their relative impact on social mobility.

- Describe and compare the major social classes in the United States, using income, wealth, occupation, and educational attainment to distinguish among the upper, middle, working, and underclass strata.

- Analyze the concept of social mobility, including upward, downward, intergenerational, and intragenerational forms, and explain how these reflect the openness of a society.

- Evaluate the structural factors that influence social mobility, including family wealth, geographic location, education, social networks, race, and gender.

- Apply Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital and Annette Lareau’s theories of parenting to understand unequal access to opportunity.

- Interpret how opportunity hoarding and exclusionary zoning preserve class privilege and reproduce inequality, as described by Richard Reeves and Raj Chetty.

- Compare three sociological theories of poverty, including:

- Matthew Desmond’s conflict theory, which views poverty as politically maintained for the benefit of others;

- Charles Murray’s individual responsibility critique of welfare, and its implications for policy;

- Herbert Gans’s functionalist perspective, which outlines the societal functions poverty serves for the middle and upper classes.

- Critically assess the debates around poverty policy and social programs, engaging with both supporting evidence and major critiques of each theoretical approach.

- Reflect on the broader implications of class-based inequality, including how stratification shapes access to institutions and intersects with race, gender, and public policy.

Introduction

Imagine living in a world where your entire future—your job, your wealth, your social connections—was determined the moment you were born. For many, this is not just a hypothetical scenario but a lived reality. Whether it was the caste system in India, the rigid social hierarchies of feudal Europe, or the economic disparities in modern-day capitalist societies, social stratification has been a fundamental aspect of human civilization throughout history.

Even today, inequality persists in striking ways. In the United States, for example, the top 10% of households hold nearly 70% of the nation’s wealth, while the bottom half owns less than 2% (Source). Such disparities underscore a critical question: how is society structured in a way that allows some to accumulate immense power and wealth, while others struggle to meet their basic needs?

For sociologists, understanding social stratification is crucial because it reveals the underlying structures that shape people’s lives and opportunities. Stratification doesn’t just describe how wealth or power is distributed—it exposes the deep-seated social forces that influence everything from access to education and healthcare to patterns of social mobility and inequality. By studying stratification, sociologists can better understand the root causes of social problems and propose solutions for creating more equitable societies.

Social Stratification

Social stratification refers to the structured inequality in societies, where individuals are grouped and ranked into hierarchical layers based on factors like wealth, power, prestige, and education. These rankings profoundly impact people’s lives, determining not only their access to resources but also their overall quality of life. Importantly, stratification is not random; it is an enduring system built on deeply entrenched social, economic, and sometimes legal structures that perpetuate inequality over generations.

Types of Social Stratification

The systems of stratification differ in how rigid or flexible they are. In closed systems of stratification, individuals are born into their social rank, and there is little to no possibility for movement between strata. A notable example of this is the caste system, historically practiced in India. In this system, an individual’s social position is determined at birth and remains fixed throughout their life. Caste determines everything from occupation to social interactions, creating a deeply entrenched and rigid hierarchy.

Another form of closed system was feudalism, prevalent in medieval Europe. Under feudalism, society was organized into a rigid hierarchy of nobles, clergy, and peasants. The status one was born into largely dictated one’s role in life, with little room for mobility. A peasant’s child, for example, would almost certainly remain a peasant.

By contrast, open systems offer more potential for social mobility. Capitalist societies, for instance, are structured around class stratification. While class-based systems are still hierarchical, individuals have more opportunities to change their social position, typically through education, employment, and economic success. However, this mobility is not as open as it might seem. While it is theoretically possible to move from the lowest class to the highest, the reality is that the barriers to such mobility are significant, often due to deeply ingrained economic inequality.

Other Key Concepts in Stratification

To understand social stratification, it’s essential to define several key terms. Class, for instance, refers to a group of people with a similar economic standing in society. Class is often determined by factors like income, education, and occupational prestige. These aspects contribute to what sociologists call socioeconomic status (SES), a composite measure that incorporates not only a person’s income but also their level of education, their occupation, and the overall prestige associated with that occupation.

While income—the money one earns through work or investments—is an important factor in determining social class, wealth—the total value of one’s assets—often plays an even greater role in defining one’s long-term social standing. Wealth includes property, savings, investments, and other assets that can provide financial security across generations. This distinction between income and wealth is crucial because while income can fluctuate, wealth tends to accumulate over time, often creating profound disparities between individuals and groups.

Finally, an important concept related to these terms is status consistency, which refers to how aligned an individual’s various social statuses are. For example, someone with a high income but a low-prestige job (e.g., garbage collector) may experience status inconsistency. In contrast, someone who is wealthy, well-educated, and holds a prestigious position would have a high degree of status consistency (e.g., surgeon).

Class Stratification and the Challenges of Social Mobility

Class stratification remains one of the most enduring forms of social inequality in modern societies. It divides individuals based on economic factors such as income, wealth, education, and occupation, creating a hierarchy that impacts every aspect of life. In the United States, sociologists typically distinguish six primary classes, each with distinct characteristics.

The Upper Class (5%)

At the top of the social ladder is the upper class, comprising about 5% of the population. This class is defined not just by income, which exceeds $200,000 annually, but more significantly by wealth—accumulated assets such as property, investments, and inheritances. The upper class wields considerable influence in society, controlling major economic, political, and social institutions.

A significant portion of the upper class consists of the power elite, a term coined by sociologist C. Wright Mills in his 1956 book The Power Elite. Mills argued that this small group of individuals holds the most power in society by dominating key institutions in the military, government, and economy. Despite their relatively small numbers, the upper class, particularly the power elite, significantly shapes policy and public opinion, reinforcing their own status.

While the upper class has become more diverse over time, barriers to entry remain substantial, as wealth is often inherited and social networks are exclusive, perpetuating inequality over generations.

The Upper-Middle Class (15%)

Next is the upper-middle class, which makes up roughly 15% of the population. Members of this class earn between $100,000 and $200,000 annually, typically hold graduate degrees, and occupy upper white-collar managerial roles or are small business owners. Education is a key marker of the upper-middle class, with advanced degrees serving as both a status symbol and a gateway to high-paying professions.

While this class enjoys significant economic security, much of their stability depends on maintaining their educational and professional standing. For the upper-middle class, education and career success are essential to maintaining their position and passing on advantages to the next generation.

The Lower Middle-Class (40%)

Comprising 40% of the population, the lower middle-class includes those earning between $40,000 and $100,000 annually. This group includes professionals such as teachers, nurses, and other skilled workers who typically hold four-year degrees. While the lower middle-class experiences more economic pressure than the upper-middle class, they still maintain a degree of stability, particularly through steady employment in sectors that provide benefits such as healthcare and pensions.

However, members of the lower middle-class are vulnerable to financial instability, particularly during economic downturns or in the face of rising living costs. Despite this, they remain committed to upward mobility, often placing a strong emphasis on education and professional development as pathways to greater economic security.

The Working Class (20%)

The working class makes up about 20% of the population and is characterized by annual earnings between $20,000 and $40,000. Jobs in this class are often manual labor or service industry roles, sometimes referred to as blue-collar (physical labor) or pink-collar (service-oriented) work. The educational attainment of the working class is typically lower than that of the middle classes, with many workers holding only high school diplomas or associate degrees.

Although members of the working class often work long hours in physically demanding jobs, they tend to have limited access to upward mobility. Job security can be precarious, and benefits such as healthcare or retirement plans are less common. The working class faces significant challenges in achieving economic stability, with many experiencing financial insecurity despite being employed.

The Working Poor and Underclass (20%)

Another 20% of the population falls into the category of the working poor and the underclass. These groups are defined by annual earnings of less than $20,000. The working poor, despite being employed, often in unskilled, low-wage jobs, struggle to meet their basic needs. Jobs in this category tend to be unstable and lack benefits, making it difficult for individuals to escape poverty.

Many working poor individuals live paycheck to paycheck, and their employment is often part-time or temporary, making it difficult to build long-term financial security. The working poor are frequently caught in a cycle of economic hardship, as low wages and lack of opportunities for education or advancement limit their ability to improve their situation.

At the bottom of the social hierarchy is the underclass. The underclass consists of individuals who experience chronic unemployment and face severe economic and social disadvantages. They often live in neighborhoods characterized by high levels of poverty, crime, and limited access to education and healthcare. This group is disproportionately made up of people of color living in urban, inner-city areas.

The underclass faces systemic barriers that make upward mobility nearly impossible. For many, opportunities for stable employment are scarce, and access to education, healthcare, and social services is limited. This class remains largely marginalized, with few pathways out of poverty.

Social Mobility: The Fluidity of Class Boundaries

While social stratification often suggests a fixed structure of classes, there remains the possibility for individuals to move between these strata—a phenomenon known as social mobility. Social mobility is not just a matter of personal ambition or hard work; it reflects how open or closed a society is in terms of allowing people to improve (or worsen) their social standing. Sociologists are particularly interested in social mobility because it reveals the flexibility of a class system and highlights the opportunities or constraints that individuals face over their lifetimes and across generations.

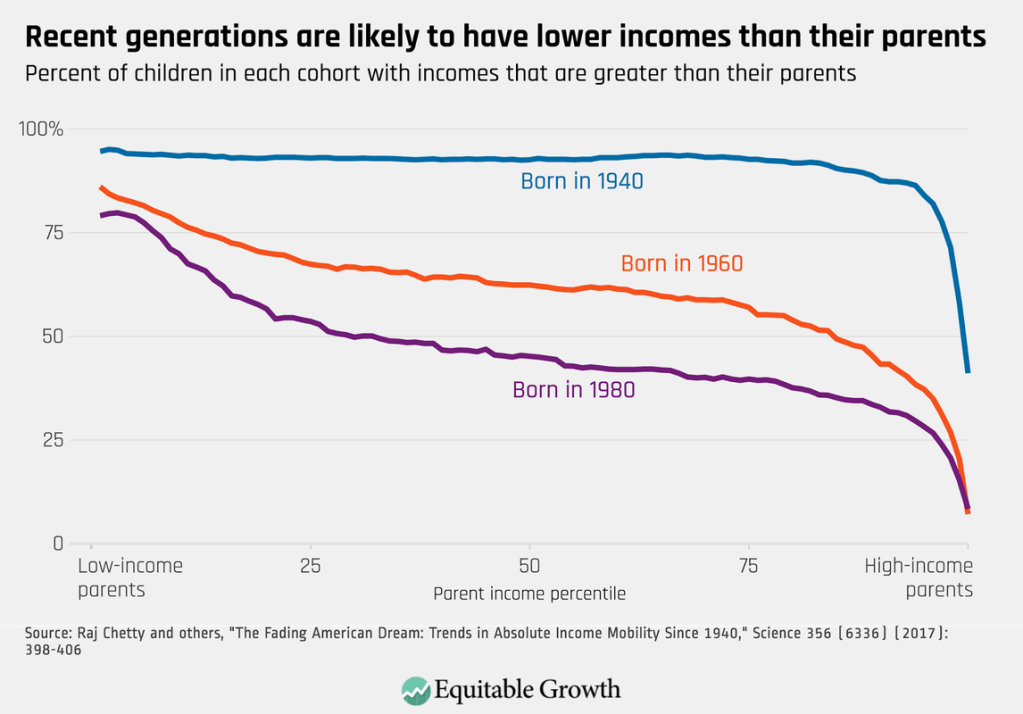

The concept of social mobility is multifaceted, involving various types of movement through the social hierarchy. In societies like the United States, where the “American Dream” is often cited as an ideal, the promise of upward mobility—rising from modest means to achieve success—forms a core part of the national narrative. However, mobility is not guaranteed, and it can also work in reverse, with some individuals experiencing a downward slide.

Types of Social Mobility

Social mobility itself is a broad term, referring to the shifts in social position that individuals or groups experience. These movements can be upward, downward, or occur over different time frames. Understanding the specific types of mobility helps clarify how these movements happen and the patterns that emerge within societies.

Upward Mobility

When people think of social mobility, they most often think of upward mobility, where an individual or group moves to a higher social class. For example, a person born into a working-class family who obtains a college degree and lands a high-paying job in a managerial role is considered to have achieved upward mobility. This movement signifies not just increased income but also greater access to social resources, like better education and healthcare.

Downward Mobility

Social mobility is not always positive. Downward mobility occurs when individuals fall into a lower social class. This can happen due to factors such as job loss, economic recession, or health problems that result in lost income. For instance, the 2008 financial crisis pushed many middle-class families into financial precarity, as people lost jobs, homes, and retirement savings. For those affected, this was a stark example of how quickly downward mobility can occur, even in relatively stable lives.

Intergenerational Mobility

The concept of intergenerational mobility deals with the movement between classes from one generation to the next. This type of mobility is often seen as a measure of a society’s fairness—how much one’s background dictates future success. For example, if a child of low-income parents grows up to become a well-educated professional, that demonstrates intergenerational upward mobility. Societies with high levels of intergenerational mobility are seen as offering more equal opportunities, allowing individuals to rise based on their talents and efforts rather than their family background.

Intragenerational Mobility

Intragenerational mobility refers to changes in social position that occur during an individual’s lifetime. For instance, a person might start their career in a low-paying job and gradually move up to a more prestigious position with higher pay and greater influence. Conversely, a person may experience downward intragenerational mobility due to business failures or personal setbacks. This type of mobility is particularly significant because it shows how fluid an individual’s social standing can be over the course of their life.

These various forms of social mobility reveal that class is not always static. However, while movement is possible, the pathways to upward mobility are often more difficult than they seem. Social mobility is shaped by a number of factors, which we will explore in the following section. From family wealth and geographic location to race and gender, these elements can either create opportunities or reinforce the barriers that prevent individuals from moving up the social ladder.

Factors Influencing Social Mobility

Social mobility is shaped by a range of structural factors that either facilitate or obstruct movement between social classes. While individual effort and talent are important, factors such as family wealth, geographic location, education, social networks, cultural capital, race, and gender often play a more significant role in determining whether individuals can improve their social standing.

Family Wealth

One of the most significant determinants is family wealth, which gives access to critical resources such as high-quality education and better job opportunities. Richard Reeves, in his 2017 book, Dream Hoarders, argues that the upper middle class (the top 20% of earners) uses their wealth to maintain their status across generations through “opportunity hoarding“. This involves practices like buying homes in affluent neighborhoods with top-tier public schools, paying for private education, and securing high-paying internships through personal networks. Wealth ensures that children from upper-middle-class families receive the best opportunities, creating a significant advantage over children from lower-income backgrounds, who are less likely to escape their economic situation. Studies show that 60% of children born into the top 20% remain in that bracket as adults, demonstrating how wealth perpetuates itself (Source).

Geographic Location

Geographic location further compounds this disparity. As Reeves points out, exclusionary zoning keeps affordable housing out of wealthier areas, thereby limiting access to high-quality schools and other resources for lower-income families. Raj Chetty’s research underscores this point, showing that children who grow up in economically diverse areas are more likely to experience upward mobility than those raised in segregated, low-income neighborhoods. The increasing concentration of both upper- and lower-income families in geographically distinct areas, as highlighted by your data, illustrates how geographic location can either open doors or trap individuals in poverty.

Education

When it comes to education, the opportunities available to children from upper-middle-class families far exceed those of their lower-income peers. Reeves argues that unfair college admissions practices—like legacy preferences and access to expensive test prep and extracurriculars—disproportionately benefit the wealthy. Moreover, sociologist Annette Lareau’s research in Unequal Childhoods adds another layer to this analysis by focusing on the role of parenting styles. Lareau distinguishes between concerted cultivation, a parenting style used by middle- and upper-middle-class families, and natural growth, more common in working-class families. In the concerted cultivation model, parents actively cultivate their children’s talents and skills, enrolling them in organized activities, encouraging communication with authority figures, and teaching them to advocate for themselves in institutional settings. This closely aligns with sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital, where children learn behaviors and knowledge that are valued in educational and professional environments. These children are equipped with the tools to navigate elite educational institutions, giving them a considerable advantage in achieving upward mobility.

By contrast, Lareau’s concept of natural growth describes working-class and poor families, who encourage their children to be more independent and let them develop organically. These children are often not socialized into the same behaviors and language that institutions favor, which can put them at a disadvantage in settings like schools and job interviews. As a result, they may struggle to access the same educational and career opportunities as their more privileged peers, reinforcing the barriers to upward mobility.

Social Networks

Social networks further exacerbate these inequalities. Reeves, in his book, Dream Hoarders, points to the informal allocation of internships as a key example of how the upper middle class hoards opportunities. Upper-middle-class families often have well-established professional networks that can secure internships and jobs for their children, even when those opportunities are unpaid. This gives them invaluable work experience and connections that can lead to high-paying jobs after graduation. Those without such networks, particularly children from lower-income families, miss out on these opportunities, which limits their ability to move up the economic ladder.

Race and Gender

Additionally, race and gender compound the barriers to mobility. As we’ll see in future modules, structural racism and sexism affect access to education, housing, and employment, limiting opportunities for minority groups and women. Reeves argues that the intersection of race and class further disadvantages Black and Hispanic families, who face both economic and racial barriers to upward mobility. For instance, Black Americans born into poverty are much less likely to achieve upward mobility than their White counterparts (Source). Similarly, women, especially women of color, face additional challenges in securing leadership positions or high-paying jobs due to gender biases in hiring and promotion practices (Source).

In summary, social mobility is shaped by numerous interlocking factors, with opportunity hoarding by the upper middle class exacerbating the challenges faced by lower-income individuals. Through mechanisms like exclusionary zoning, inequitable college admissions, and the cultivation of cultural capital, the wealthy maintain their advantages and restrict access to resources that could foster upward mobility for others. By understanding how these factors interact, we can better address the structural inequalities that limit social mobility and perpetuate class divisions.

Debating Poverty: Three Sociological Views

Poverty is generally understood as a state in which individuals or groups lack the financial resources necessary to meet basic needs, including food, housing, healthcare, and education. This condition, while primarily measured in economic terms, extends far beyond a lack of income. It involves social exclusion, limited opportunities, and constrained access to the resources that are essential for personal and societal development. Sociologists study poverty not only as a material condition but also as a social problem—one that is deeply embedded in the larger structures of class stratification.

Class stratification refers to the hierarchical arrangement of individuals in society based on wealth, power, and status. Those at the top of this structure, the wealthy and elite classes, possess not only material advantages but also greater social and cultural capital, allowing them to perpetuate their dominance across generations. In contrast, those at the bottom, who experience poverty, are often trapped in cycles of disadvantage. Poverty, therefore, is a product of the broader social stratification system, which organizes society into classes based on unequal access to resources.

As a social problem, poverty reflects deep-rooted inequalities that go beyond individual choices or abilities. It is a reflection of societal structures that favor certain groups while marginalizing others. The existence of poverty raises questions about fairness, justice, and the allocation of resources within society. Sociologists have long studied the causes and consequences of poverty, offering various explanations that range from functionalist to conflict theory perspectives, and from micro-level analyses to macroeconomic and global frameworks. In this section, we will be looking at numerous sociological works that analyze poverty from different perspectives.

Conflict Theory: Matthew Desmond

Sociologist Matthew Desmond challenges conventional perspectives on poverty, arguing that it is not simply an unfortunate byproduct of economic systems but rather an intentional outcome of political and structural choices. In his book Poverty, By America, Desmond reframes poverty not as an individual failing but as a condition maintained by those who benefit from it. He asserts that poverty in the United States persists because the wealthy and middle class, often unknowingly, sustain and profit from policies and systems that keep people poor.

Unlike perspectives that attribute poverty to lack of effort, Desmond argues that structural factors—including housing policies, tax structures, and labor market dynamics—create conditions where poverty is entrenched. Furthermore, he asserts that poverty reduction is not a matter of increasing charity but rather changing the very systems that allow poverty to exist in the first place.

How the Wealthy and Middle Class Benefit from Poverty

One of Desmond’s key arguments is that poverty is sustained because it benefits those above the poverty line. He highlights how government subsidies, tax loopholes, and financial policies disproportionately favor the middle class and the wealthy while leaving low-income individuals struggling. For example, tax deductions for homeownership and college savings plans overwhelmingly benefit higher-income households, while renters and those unable to save for college receive little support. These policies redistribute resources upward rather than addressing economic disparity.

Desmond also explores how poverty is financially exploited through predatory industries. Payday lenders, high-interest loan providers, and even landlords charging excessive rents in low-income areas extract wealth from the poor, reinforcing their economic struggles. He refers to this as a system in which “poverty is big business,” where industries profit from those with the least financial stability.

The “High Cost of Being Poor”

A central theme in Desmond’s work is the paradox that being poor is often more expensive than being wealthy. Low-income individuals pay disproportionately higher rates for basic goods and services—whether through high-interest loans, exploitative rental agreements, or excessive bank fees for account overdrafts. He explains that those in poverty often face financial penalties simply for lacking access to better banking services, affordable housing, or stable employment.

For example, renters in low-income neighborhoods frequently pay more per square foot for housing than homeowners do in affluent areas. Without savings or credit history, they may be forced to accept high-interest loans or expensive short-term financing options, making it nearly impossible to escape economic hardship.

The Political Nature of Poverty

Unlike theories that frame poverty as an economic inevitability, Desmond argues that poverty is primarily a political problem. He critiques the idea that market forces alone determine economic outcomes, showing instead that government policies actively shape poverty. He points to the COVID-19 pandemic as evidence: temporary social programs, including stimulus payments and expanded child tax credits, dramatically reduced poverty in the U.S. in 2020. However, once these programs were rolled back, poverty levels quickly rebounded. Desmond uses this example to demonstrate that policy changes can significantly impact poverty rates—meaning that poverty persists not because it is unavoidable, but because political choices allow it to continue.

Another major factor Desmond highlights is the lack of political will to address poverty comprehensively. He critiques both conservative and progressive approaches, arguing that conservatives often downplay structural causes of poverty, while progressives fail to acknowledge how their own class benefits from economic inequality. He calls for a mass movement to demand political and economic changes, recognizing that without collective action, those in power will continue to prioritize policies that benefit the wealthy at the expense of the poor.

Proposed Solutions to Poverty

Desmond’s vision for poverty reduction is rooted in two key principles: fair taxation and organized social movements.

- Tax Reform – Desmond argues that if the wealthy and middle class paid their fair share of taxes and if tax loopholes were eliminated, substantial funds could be redirected toward poverty reduction programs. He highlights that corporate tax breaks and financial incentives often dwarf the spending on direct poverty relief, reinforcing economic disparities.

- Social Movements and Political Pressure – Desmond emphasizes that meaningful change will not happen unless people demand it. He argues that poverty persists because those who benefit from the current system are not incentivized to change it. To combat this, he calls for a broad-based movement that unites people across political and economic divides to push for reforms that would address systemic inequality. He cites examples where working-class individuals, including those with opposing political ideologies, found common ground on issues such as raising the minimum wage.

While Desmond’s analysis offers a compelling critique of poverty’s structural causes, his proposed solutions have been met with skepticism.

Criticism of Desmond

While Poverty, By America has been praised for bringing attention to the realities of poverty in the United States, not everyone agrees with Matthew Desmond’s arguments. Some critics believe that his book oversimplifies complex economic issues, while others argue that his proposed solutions lack clear direction. It’s important to note that most of these critiques come from journalists, policy analysts, and think tanks—not from sociologists who specialize in studying poverty and inequality.

One major criticism comes from Reason, a magazine that focuses on individual freedoms and economic policy. Writer Aaron Brown argues that Desmond doesn’t fully explain why poverty exists, instead relying on broad claims like “poverty persists because some wish and will it to.” Brown believes that Desmond blames the wealthy and middle class without showing enough evidence that their actions directly cause poverty (Link).

The Cato Institute, a think tank that promotes free-market policies, takes a similar stance. Their review argues that Desmond’s book doesn’t fully prove that poverty is the result of systemic exploitation. Instead, they claim that he presents his argument as if it’s obviously true without giving enough facts to back it up (Link).

Another critique comes from City Journal, which focuses on urban policy and economics. Their review suggests that Desmond misrepresents poverty statistics by relying on outdated measures. They argue that he doesn’t fully account for modern government assistance programs, such as food stamps and housing aid, which have helped millions of people. Because of this, City Journal claims that Desmond paints a more extreme picture of poverty than what current data shows (Link).

Finally, Jacobin, a magazine that supports democratic socialism, offers a different perspective. While they agree with Desmond that poverty is a major issue, they believe he focuses too much on individual responsibility instead of looking at deeper economic structures. In other words, they argue that Desmond’s solutions—such as asking people to fight for change—don’t do enough to address the root causes of inequality, like corporate power and labor exploitation (Link).

Despite these critiques, Poverty, By America remains an important book for sparking conversations about poverty and inequality. Even if people disagree with Desmond’s ideas, his work challenges readers to think about the ways that economic systems shape our everyday lives.

Dysfunctions of Welfare: Charles Murray

Our second theorist follows a more conservative approach to looking at poverty. Charles Murray is one of the most controversial social scientists of modern times, known for his provocative views on poverty, welfare, and social policy. His 1984 book, Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950-1980, was groundbreaking but also deeply divisive. In the book, Murray argues that the welfare policies enacted as part of the War on Poverty in the 1960s actually made poverty worse by removing incentives for self-sufficiency and promoting dependency on government aid. His work profoundly influenced welfare reform in the 1990s (Source), but it has also attracted widespread criticism for its focus on individual responsibility at the expense of acknowledging structural inequalities.

Welfare as the Cause of Poverty

In Losing Ground, Murray asserts that many of the government programs aimed at reducing poverty and inequality in the United States have backfired. He argues that by providing financial assistance to the poor, the government inadvertently created a system where people were disincentivized to work, marry, and take responsibility for their actions. According to Murray, the expansion of welfare programs led to an increase in poverty, rather than its alleviation, by fostering a culture of dependency.

Murray’s core claim is that welfare policies undermined personal responsibility and discouraged productive behaviors. He points to the rise in out-of-wedlock births, particularly among low-income women, and the decline in workforce participation among able-bodied adults as evidence that welfare programs discouraged people from engaging in the behaviors necessary to escape poverty. For Murray, welfare programs, such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), encouraged single motherhood by providing financial support to unmarried women, which he believes led to an increase in poverty rates over time.

He presents statistical evidence showing that, despite increased welfare spending, poverty rates stopped declining in the 1970s and other social problems, like crime, escalated. Murray argues that these issues were not only economic but cultural, with welfare policies reshaping attitudes and behaviors, particularly among the poor. He contends that welfare made it easier for individuals to avoid taking personal responsibility for their lives, thus exacerbating the very problems it was designed to solve.

As a solution, Murray advocates for eliminating welfare programs entirely. He suggests that the only way to reverse the harm caused by welfare is to stop providing financial support to the poor. Murray argues that cutting off government aid would force individuals to take personal responsibility for their economic situations, leading to a decrease in poverty over time as people would be encouraged to find work and form stable families. He asserts that the free market and individual initiative are more effective at reducing poverty than government intervention.

Criticisms of Murray

Murray’s conclusions have sparked widespread criticism, particularly from scholars who argue that he overlooks the structural causes of poverty and places undue blame on the behaviors of poor individuals. One of the primary critiques of Losing Ground is that Murray largely ignores the role of systemic factors such as racial discrimination, educational inequality, and the decline of manufacturing jobs, all of which contributed to rising poverty levels during the period he examines.

For instance, sociologist William Julius Wilson, in his 1987 book, The Truly Disadvantaged, argues that the disappearance of well-paying jobs in urban areas, rather than the expansion of welfare programs, played a significant role in deepening poverty, especially among Black Americans. Wilson contends that welfare may have provided a necessary safety net in the face of deindustrialization and job loss, and that Murray’s focus on personal responsibility fails to account for the broader economic forces at play.

Additionally, critics like Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, in their book, Regulating the Poor, don’t directly critique Murray but challenge his view that welfare recipients are dependent and avoid work. They argue that most people who receive welfare want to work but are often trapped in low-wage jobs that do not provide enough income to support a family. Welfare, they argue, helps fill the gap left by an inadequate labor market and should not be viewed as a disincentive to work.

Another major criticism of Murray is brought by sociologist, Christopher Jencks, in his 1985 article, “How Poor are the Poor.” In the article, Jencks argues that Murray oversimplifies the causes of welfare dependency by focusing too narrowly on welfare programs as the primary reason for poverty. Jencks points out that other factors—such as the lack of well-paying jobs, systemic barriers, and inadequate education—play a far greater role in keeping people impoverished. He also criticizes Murray for selectively using data, ignoring evidence that many welfare recipients do work but are stuck in low-wage jobs that don’t provide enough to live on. Jencks further contends that Murray’s analysis overlooks key structural changes in the economy, like the decline of stable manufacturing jobs and the rise of low-wage service work, which limit upward mobility and contribute significantly to persistent poverty. Ultimately, Jencks sees Murray’s conclusions as a misreading of the real dynamics behind poverty.

Functionalism: Herbert Gans

Lastly, I want to look at why some scholars believe that poverty isn’t so much a structural part of society, or something caused by political institutions, but instead functional to the operation of society.

Herbert Gans is an influential American sociologist known for his work in urban sociology, social planning, and social theory. Over his extensive career, Gans has focused on understanding the dynamics of cities, media, and social inequality. His contributions to sociology are particularly notable in his critique of urban renewal policies in the 1960s and his insights into the role of poverty in society. Gans’s work often bridges both theory and practical application, bringing a nuanced understanding to how social structures, particularly urban ones, impact people’s lives.

One of Gans’s most cited works is his 1972 article, “The Positive Functions of Poverty,” where he presents a functionalist perspective on poverty. Functionalism is a sociological theory that examines the structures of society and how they work to maintain social order. From this viewpoint, various elements of society, even those that seem negative, can have functions that contribute to the overall stability of society. In this context, Gans argues that poverty, while harmful to the poor themselves, serves a range of functions that benefit other groups in society, particularly the affluent.

The Functions of Poverty

According to Gans, poverty fulfills several functions for society. These functions include:

- Low-Wage Labor Supply: Poverty ensures the existence of a low-wage labor force willing to take on jobs that are unpleasant, dangerous, or low-status. Many of these jobs, such as janitorial work, farm labor, or service industry roles, are essential for the economy to function. However, they are often poorly paid and offer little opportunity for advancement, making them unattractive to those in higher social classes. The presence of poverty ensures that these jobs will always have workers.

- Job Creation for the Middle and Upper Classes: Gans argues that poverty helps create employment opportunities for individuals who work in fields that address or manage poverty. For instance, social workers, legal aid attorneys, and welfare case managers all have careers that depend on the existence of poverty. Additionally, industries such as law enforcement and prison systems also derive their existence, in part, from the management of economically disadvantaged populations.

- Moral and Cultural Boundaries: Poverty helps to reinforce moral distinctions between the “deserving” and “undeserving” in society. Gans suggests that wealthier individuals benefit from a sense of moral superiority over those who are poor, as they can frame their success as a result of hard work and virtuous behavior. This division creates clear cultural boundaries between social classes and supports dominant societal norms.

- Social Norm Reinforcement: The existence of poverty serves as a deterrent, reinforcing the value of hard work and obedience to societal norms. Those who are poor serve as a negative reference point for the middle and upper classes, reminding them of what happens when individuals do not “succeed” in a capitalist society.

- Scapegoating and Blaming: Poverty also allows for marginalized groups to be scapegoated for broader societal problems. When there are social or economic issues, the poor are often blamed for these problems, allowing more privileged classes to avoid scrutiny or responsibility for systemic issues.

- Providing Cheap Goods and Services: The poor often serve as a consumer base for low-cost goods and services. In many cases, the poor must buy second-hand items or seek out low-quality services, which supports certain sectors of the economy. For example, payday lenders, discount retailers, and low-cost housing landlords all profit from the economic circumstances of the poor.

Criticisms of Gans’s Functionalist Perspective

While Herbert Gans’s functionalist approach provides a thought-provoking analysis of the role poverty plays in maintaining societal order, it has faced significant criticism, particularly from the perspective of conflict theory. One of the primary critiques is that Gans’s focus on the “positive functions” of poverty risks normalizing its existence. Michael B. Katz, in his book The Undeserving Poor (1989), argues that by focusing on the functions poverty serves for the wealthy, Gans inadvertently downplays the harmful effects that poverty inflicts on those experiencing it. Katz and others suggest that Gans’s perspective can reinforce the idea that poverty is an inevitable or necessary part of society, rather than a serious social problem that must be addressed. This view, critics claim, supports the status quo, as it does not challenge the systems that perpetuate poverty and inequality.

Another significant critique comes from Michael Parenti in his work Power and the Powerless (1978). Parenti, from a conflict theory perspective, argues that Gans’s analysis overlooks the power dynamics at play in society. Functionalism often assumes that societal institutions work to maintain stability and order, but Parenti contends that poverty is not merely an unintended consequence of the system—it is a deliberate result of the inequalities maintained by those in power. In this view, poverty serves the interests of the wealthy and powerful by keeping a low-wage labor force available. Parenti criticizes Gans’s functionalist approach for failing to confront how economic and political elites use their influence to perpetuate poverty and inequality, making it not an unfortunate necessity but a direct consequence of exploitation.

Conclusion

In examining social stratification and class, we see that inequality is not just about individual outcomes but is deeply embedded in the structures of society. Social stratification, which divides people into hierarchies based on wealth, power, and prestige, operates through systems like class, with clear divisions between the upper class, middle class, working class, and the poor. These divisions influence everything from access to education and jobs to social mobility—the ability of individuals to move between classes. While there are some opportunities for mobility, factors like family wealth, geographic location, race, gender, and education often limit the chances for people to rise above their socioeconomic status.

The ongoing debate about poverty illustrates different perspectives on how inequality is maintained and challenged. Matthew Desmond’s conflict perspective argues that poverty is not simply an unfortunate byproduct of economic systems but a deliberate outcome of political and structural choices that benefit the wealthy and middle class. He contends that government policies, tax structures, and financial practices sustain poverty by redistributing resources upward, making it a systemic issue rather than an individual failing. In contrast, Charles Murray sees welfare as a key contributor to poverty, arguing that government support systems discourage work and entrench dependency, though critics highlight the oversimplifications in his views. Herbert Gans, from a functionalist perspective, suggests that poverty serves certain roles in society, but critics contend that this approach normalizes inequality without addressing the power dynamics that sustain it. Together, these perspectives underscore the complexity of social stratification and the enduring challenge of addressing poverty and inequality in a structured society.

In subsequent modules, we will explore how class-based stratification intersects with social categories of race and class, as well as how it permeates institutions such as healthcare.

Key Concepts

Caste System: A closed system of stratification where social status is inherited and assigned at birth, with little to no mobility between castes.

- Example: In traditional Indian society, individuals were born into a caste (e.g., Brahmin, Kshatriya, Dalit) and remained in that caste throughout their lives.

Class: A group of people within a society who share a similar socioeconomic status based on wealth, income, education, and occupation.

- Example: The working class, which consists of individuals who perform manual labor and earn hourly wages.

Class Stratification: The division of society into hierarchical groups based on wealth, income, education, and occupation.

- Example: The division into upper class, middle class, and working class in the United States.

Closed Systems: Social stratification systems where individuals cannot change their social position.

- Example: The caste system in India, where people are born into a social group they cannot leave.

Concerted Cultivation: A parenting style where parents actively foster and assess a child’s talents, opinions, and skills through organized activities and direct engagement.

- Example: Middle-class families enrolling children in extracurricular activities, sports, and tutoring to enhance their development.

Cultural Capital: Non-economic resources that enable social mobility, such as education, intellect, style of speech, or dress.

- Example: A person who has a prestigious degree from a well-known university may use that education to secure a high-paying job.

Downward Mobility: The movement of an individual or group to a lower social or economic status.

- Example: A worker who loses a high-paying job and is forced to take a lower-wage position, resulting in a lower standard of living.

Income: The money received by an individual or household, typically from wages, salaries, investments, or other financial sources.

- Example: A person earning $50,000 annually from their job.

Intergenerational Mobility: The movement of individuals or groups up or down the social hierarchy between generations.

- Example: A child born to parents in the working class who becomes a lawyer and moves into the upper-middle class.

Intragenerational Mobility: The movement of individuals or groups within their lifetime up or down the social hierarchy.

- Example: A person starting as a retail clerk and working their way up to become a store manager or owner.

Natural Growth: A parenting style in which children are given more autonomy to develop on their own, with fewer organized activities.

- Example: A working-class family allowing children to spend more free time playing in the neighborhood without structured extracurricular activities.

Open Systems: Social stratification systems where individuals can change their social position through achievements, such as education and income.

- Example: The class system in the U.S., where people can rise from a lower class to a higher class through career success.

Opportunity Hoarding: A practice where privileged groups maintain access to resources or opportunities, preventing others from gaining them.

- Example: Wealthy families using their influence to secure unpaid internships for their children, which less affluent students can’t afford to take.

Poverty: A condition in which individuals lack sufficient income or resources to meet basic needs, such as food, shelter, and healthcare.

- Example: A family living below the poverty line, unable to afford adequate housing or medical care.

Power Elite: A small group of wealthy and influential individuals who hold the majority of power in a society.

- Example: Top corporate executives, political leaders, and military officials who make key decisions affecting the entire country.

Social Mobility: The movement of individuals or groups between different positions within the social hierarchy.

- Example: A person from a working-class background obtaining a college degree and moving into a higher-income profession.

Social Problem: A societal issue that negatively impacts a large group of people and requires intervention to solve.

- Example: Homelessness, which affects individuals’ well-being and requires policy solutions to address housing and economic inequality.

Social Stratification: The hierarchical arrangement of individuals in society based on factors like wealth, power, and prestige.

- Example: The division between the wealthy elite and the working class in modern societies.

Socioeconomic Status (SES): A combined measure of an individual’s or group’s economic and social position in relation to others, based on income, education, and occupation.

- Example: A person with a college degree, a high-paying job, and an upper-middle-class income level.

Status Consistency: A situation in which an individual’s social status is similar across various aspects, such as wealth, education, and occupation.

- Example: A doctor who is highly educated, earns a high income, and has high social prestige.

Status Inconsistency: A situation in which an individual’s social status varies significantly across different areas, such as wealth, education, and occupation.

- Example: A highly educated individual working in a low-paying job, such as a PhD holder working as a barista.

Underclass: A social group at the very bottom of the social hierarchy, often characterized by chronic poverty and unemployment.

- Example: People living in high-poverty inner-city neighborhoods with limited access to jobs, education, or upward mobility.

Upward Mobility: The movement of an individual or group to a higher social or economic status.

- Example: A first-generation college graduate who enters a high-paying profession and moves into the upper-middle class.

Wealth: The total value of all financial assets and property owned by an individual or household, minus any debts.

- Example: A person who owns a home, investments, and savings totaling $1 million.

Reflection Questions

- What are the key structural factors identified in the reading that influence social mobility, and how do these factors interact to either enable or constrain movement between social classes?

- How does the concept of status consistency help sociologists understand the complexities of class identity beyond just income or occupation?

- How do the theories of Matthew Desmond, Charles Murray, and Herbert Gans differ in their explanations of poverty, particularly regarding who is responsible for its persistence and what solutions are most effective?

- What is the relationship between geographic location and social mobility, and how do Richard Reeves’s and Raj Chetty’s findings illustrate the influence of housing policy and neighborhood resources on long-term outcomes?