Table of Contents

- Learning Objectives

- Introduction

- Defining Sex: Binary or Spectrum

- Defining Gender: A Social Construct

- Theoretical Viewpoints

- Flipping the Narrative: Challenges Faced by Men in Modern Society

- Conclusion

- Key Concepts

- Reflection Questions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, students will be able to:

- Differentiate between sex and gender, explaining how each is understood biologically and sociologically.

- Assess the limitations of binary models of sex and gender, using insights from science and social theory.

- Explain how structural functionalism, symbolic interactionism, and conflict theory (including feminist theory) approach gender differently.

- Analyze key feminist concepts such as patriarchy, hegemonic masculinity, emphasized femininity, the double bind, and intersectionality.

- Discuss the challenges women face in leadership roles, including the glass ceiling and motherhood penalty.

- Evaluate C. J. Pascoe’s research on gender policing and Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity.

- Identify contemporary challenges facing men, drawing on Richard Reeves’s work on education, work, fatherhood, and masculinity.

- Consider how evolving definitions of masculinity and femininity open possibilities for more inclusive and equitable societies.

Introduction

In 2009, South African runner Caster Semenya stunned the world by winning gold in the 800 meters at the World Championships. Her victory, though celebrated for its athleticism, sparked a global controversy. Semenya was subjected to gender verification testing due to her naturally elevated testosterone levels, raising questions about her eligibility to compete as a woman. The debate resurfaced at the 2016 Rio Olympics, where she again won gold, despite regulations many saw as an attempt to police her body (Source). Semenya’s case challenges our understanding of what it means to be male or female, as international sports organizations grapple with how to categorize athletes whose biology doesn’t fit traditional definitions.

Similarly, the 2024 Summer Olympics saw Imane Khelif of Algeria and Lin Yu-ting of Taiwan disqualified from the women’s boxing competition due to elevated testosterone levels, reigniting the global conversation about rigid definitions of sex and gender (Source). These events, while situated in the world of elite sports, speak to much broader questions that have captivated sociologists, including: How do we define sex and gender? Who gets to decide? And what are the social consequences of those decisions?

At the center of this conversation are two dominant, and competing perspectives:

- Biological essentialism holds that sex and gender are determined primarily by biology, such as genes, hormones, and physical characteristics. From this perspective, male and female categories are relatively fixed and rooted in nature.

- Social constructionism, by contrast, argues that society plays a crucial role in defining and shaping what we mean by “male” and “female.” This view does not deny biology, but it emphasizes that the meaning attached to sex categories, whether they be behaviors, roles, or identities, are shaped by culture, history, and power relations.

Rather than settling the debate, this chapter explores a variety of sociological theories and perspectives that help us understand how debates over sex and gender emerge and evolve. The goal is not to decide which view is right, but to consider how different frameworks shape public discourse, policy decisions, and institutional practices. By examining these perspectives, we can better see how science, culture, and power interact in shaping categories we often take for granted.

Defining Sex: Binary or Spectrum

Sex and gender, while often used interchangeably in everyday language, are distinct concepts in sociology. Understanding their differences is crucial to analyzing how societies shape human behavior and identity.

Sex refers to the biological and physiological characteristics that distinguish males, females, and intersex individuals. According to Dalton Conley in You May Ask Yourself, sex is “the perceived biological differences that society typically uses to distinguish males from females.” These distinctions include chromosomes (XX for females and XY for males), hormones, and reproductive organs.

Gender, by contrast, refers to the roles, behaviors, and expectations that cultures assign to individuals based on their perceived sex. Gender is considered a social construct, meaning it is shaped by cultural norms, traditions, and institutions rather than being biologically determined.

While gender has often been the focus of debate and sociological analysis, sex is usually treated as a biological fact, grounded in observable traits. For much of modern history, sex has been understood in binary terms: male or female. Most people fit this binary classification, and it remains widely used in everyday life, medicine, and law.

Yet in recent years, natural scientists in fields such as genetics, endocrinology, and neuroscience have introduced research that complicates this binary view. Some scholars and researchers argue that sex may be better understood not as two fixed categories but as a spectrum of biological variation. This does not mean that male and female categories are meaningless. Rather, it acknowledges that human biology is more complex than a simple two-category system often suggests.

The following examples highlight how some scientists are reevaluating biology and challenging the simple binary of sex.

- Chromosomal variations, such as Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) or Turner syndrome (X0), complicate the traditional binary classification. These conditions, studied extensively by geneticists like David C. Page at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), show that not all individuals fit neatly into the XX (female) or XY (male) categories. Page’s work on the Y chromosome and its variations highlights how chromosomal differences can manifest in ways that challenge the binary understanding of sex.

- Hormonal variations further blur the lines. Research by endocrinologists such as Carole Hooven (author of T: The Story of Testosterone) illustrates that testosterone and estrogen levels can vary significantly across individuals, regardless of their sex. Some women naturally have high testosterone levels, and some men have low levels. These hormonal variations influence traits like muscle mass, hair growth, and behavior, but do not necessarily define a person’s sex. Hooven’s work points to how hormone levels overlap between men and women, challenging the traditional assignment of “male” and “female” hormone roles.

- Intersex individuals are born with ambiguous genitalia or chromosomal patterns that don’t fit typical male or female definitions. Anne Fausto-Sterling, a biologist and gender studies scholar, has been a leading voice in challenging the binary model of sex. In her influential work Sexing the Body (2000), she estimated that approximately 1.7% of the population is intersex, a statistic that highlights how common it is for people to be born with sex characteristics that do not align with binary definitions. Her research advocates for viewing intersex people as part of the natural diversity of human biology rather than as anomalies.

Taken together, these examples suggest that sex, like gender, may not always fit neatly into binary categories. Some scientists now view sex as existing along a continuum, where male and female are common endpoints, but not the only possibilities. This perspective has led to more inclusive discussions about identity and biology, particularly in areas such as medicine, athletics, and education.

Sociologists study these developments not to determine whether sex is binary or not, but to understand how scientific ideas, social norms, and institutional practices interact. Whether one views sex as a binary or a spectrum, what matters to sociologists is how these definitions shape the way people are categorized, treated, and understood in society.

Defining Gender: A Social Construct

While sex refers to biological differences, gender is a social construct that involves the roles, behaviors, and expectations that societies associate with being male or female. Conley defines gender as “a social position; the set of social arrangements that are built around normative sex categories.” Unlike sex, which is based on physical attributes, gender refers to the ways in which individuals perform and express their identity within the context of societal norms.

In most societies, individuals are assigned a gender at birth based on their perceived biological sex, and they are socialized into behaviors that correspond with societal expectations for masculinity or femininity. For example, men are often expected to be assertive, independent, and unemotional, while women are typically expected to be nurturing, empathetic, and supportive. However, these expectations are not fixed—they vary across cultures and change over time.

Gender, then, is not just something we are born with, but something we learn and perform based on societal norms and expectations. This distinction between sex and gender is crucial for understanding the fluidity of gender identity and how individuals navigate their place in society.

Gender as Self-Identity

While sociology often analyzes gender in terms of social norms, institutions, and collective expectations, it is also important to consider gender at the level of individual experience. Gender self-identity refers to a person’s deeply felt sense of their own gender, which may or may not align with the sex they were assigned at birth. This internal understanding shapes how people see themselves and how they wish to be recognized by others.

Some individuals identify as cisgender, meaning their gender identity aligns with their assigned sex. Others identify as transgender, where their gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. Still others identify in ways that do not fit within the traditional male–female binary. These identities include terms such as nonbinary, gender-fluid, and agender.

- Nonbinary individuals may see themselves as both male and female, somewhere in between, or outside of those categories altogether.

- Gender-fluid individuals experience changes or shifts in their gender identity over time.

- Agender individuals may not identify with any gender at all.

This perspective has gained visibility in recent years, especially in Western societies. However, many cultures around the world have long recognized more than two genders. For example:

- Two-Spirit is a term used in some Indigenous North American communities to describe individuals who fulfill unique gender roles or embody both masculine and feminine traits.

- In South Asia, the Hijra community includes individuals who identify outside the male–female binary and are legally recognized as a third gender in countries like India and Pakistan.

These examples show that gender diversity is neither new nor limited to one cultural context. What has expanded is the language, visibility, and institutional recognition of these identities.

To understand gender fully, it is useful to distinguish between self-identity and social identity. Self-identity refers to how individuals define themselves, while social identity involves how society perceives and categorizes people based on shared norms and expectations. These two aspects do not always align, which can lead to conflict or negotiation in social settings, institutions, and public discourse.

As of today, there is no fixed number of recognized genders, as gender identity is deeply personal and varies across individuals and cultures. Some lists include over 50 distinct terms, reflecting a growing recognition of diverse gender experiences. Rather being limited by rigid categories, individuals are empowered to define their identity in ways that reflect their personal experience. Gender is increasingly seen as fluid and dynamic, challenging traditional binary norms and allowing for greater freedom in self-expression. This understanding fosters inclusivity and respect for the complexity of human identity.

This understanding serves as a foundation for exploring sociological theories of gender. Do these theories treat gender as a reflection of biology, a product of social structure, or something performed in everyday life? These are the questions that help sociologists analyze how gender operates within—and against—the boundaries of both social and personal identity.

Theoretical Viewpoints

Functionalism and Gender Roles

When thinking about why societies divide gender roles the way they do, one approach comes from structural functionalism, a theoretical framework that views society as a system of interdependent parts working together to maintain order and stability. From this perspective, gender roles are not arbitrary—they develop because they fulfill important functions in the smooth operation of society.

One of the most influential voices in this tradition was Talcott Parsons, a leading American sociologist of the mid-20th century. In a series of writings, most notably in Family, Socialization and Interaction Process (1956), co-authored with Robert Bales, Parsons outlined his theory of how the nuclear family functions within modern industrial society. According to Parsons, families operate best when there is a clear division of labor between genders. He argued that men tend to take on instrumental roles—being the breadwinners, decision-makers, and external representatives of the household—while women typically fulfill expressive roles, providing emotional support, nurturing children, and maintaining internal family cohesion.

Parsons saw this arrangement not as a product of inequality, but as a way of organizing family life to best serve the needs of a complex society. He believed that when individuals specialize in different roles, families become more efficient and stable, and this stability contributes to the overall functioning of society. In his view, these roles were complementary, not competitive, and each was necessary for the reproduction of social order.

Although Parsons was writing in the context of post–World War II America, his ideas have had a lasting influence. For many decades, this model of the family, with its clearly defined gender roles, was seen as both natural and desirable, especially in policy discussions and cultural norms surrounding the so-called “traditional family.”

Even as functionalist theory has become less central in academic sociology, similar arguments continue to appear in conservative social and political discourse, particularly among commentators and activists who emphasize “family values.” In this rhetoric, traditional gender roles are often seen as the foundation of moral and social stability. Supporters argue that deviations from these roles—such as rising divorce rates, declining birthrates, or the redefinition of family structures—threaten the health of both families and societies at large.

While this view continues to resonate in some political and religious communities, it has largely fallen out of favor among sociologists, who increasingly critique its assumptions about gender, family, and inequality. Many argue that functionalist models like Parsons’ ignore the ways in which gender roles are shaped by power dynamics and cultural expectations, and they point out that the “traditional” family model is historically specific rather than universal.

Still, from a sociological standpoint, functionalism remains valuable, not because it tells us how families should be structured, but because it helps us understand how and why certain gender arrangements have been legitimized and institutionalized in specific historical contexts. It offers a framework for analyzing why societies often develop stable patterns of role differentiation, even when those patterns come under critique.

Symbolic Interactionism: Performing and Constructing Gender in Everyday Life

While structural functionalism focus on large-scale social structures, symbolic interactionism approaches gender from the ground up. This theoretical perspective emphasizes the micro-level interactions through which people create and interpret meaning. From this view, gender is not something people simply “have,” nor is it entirely imposed by external forces. Instead, gender is something people learn, negotiate, and perform through daily interactions with others. It becomes a pattern of behaviors and cues that are reinforced over time.

A key contribution here comes from Candace West and Don Zimmerman, who introduced the influential concept of “doing gender” in a 1987 article, “Doing Gender,” published in Gender and Society. According to their theory, people “do gender” by acting in ways that are socially recognized as masculine or feminine, whether it’s the way someone speaks, dresses, walks, or expresses emotion. These actions are not biologically determined, but are part of a social script that people follow, often without realizing it. This script is shaped by expectations and judgments from others, which reinforce traditional norms. For example, a boy who chooses pink clothing or avoids sports may be teased for not acting “like a boy,” while a girl who is assertive may be labeled “bossy.” These subtle forms of feedback teach people how to stay within socially acceptable boundaries.

Symbolic interactionists also highlight how institutions reinforce these performances. Think about how classrooms, workplaces, and even bathrooms are divided by gender. These spaces help organize and enforce the idea that gender is binary and stable. But interactionism also reveals how these boundaries can be contested. For instance, individuals who identify as nonbinary or transgender often disrupt traditional gender scripts, creating space for new ways of understanding and expressing gender. From this perspective, change doesn’t always come from top-down policy shifts—it often emerges through everyday interactions that challenge the status quo.

This approach aligns in some ways with Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity, outlined in her book, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990). Like West and Zimmerman, Butler argues that gender is not a fixed identity, but something that is continuously enacted. However, Butler takes this further, suggesting that there is no “true” gender beneath the performance; gender itself is the result of repeated behaviors that become naturalized over time. These insights have influenced not only academic theory but also broader discussions around gender identity, inclusion, and self-expression.

Symbolic interactionism helps us see that gender is always in motion. It is shaped by the meanings we attach to actions, the roles we play, and the responses we receive from others. At the same time, theorists like Judith Butler remind us that these everyday performances do not happen in a vacuum. They take place within broader cultural and institutional contexts that privilege certain gender expressions while stigmatizing others. In this sense, symbolic interactionism highlights how gender is constructed and negotiated through interaction, while Butler’s work shows how those interactions are shaped and constrained by systems of power. Together, these perspectives provide a fuller picture of how gender norms are produced, reinforced, and sometimes resisted in everyday life.

Conflict Theory and Feminist Perspectives of Gender

While structural functionalism views gender roles as necessary for maintaining social order, and symbolic interactionists look at how gender is constructed through interaction, conflict theory offers another perspective by focusing on inequality and power. It asks how gender roles benefit some groups while disadvantaging others, emphasizing that social structures often serve the interests of dominant groups.

A key branch of this perspective is feminist theory, which centers on how patriarchal systems create and maintain gender-based hierarchies. Feminist theorists argue that gender roles are not natural or fixed, but socially constructed and deeply embedded in institutions such as the family, workplace, and media. These roles often privilege certain forms of masculinity while marginalizing women and those who do not conform to traditional gender norms, making gender a central axis of social stratification and power.

In the following section, we explore key concepts and sociological theories that emerge from this perspective, including patriarchy, hegemonic masculinity, and the gendered dynamics of leadership and identity. Because conflict theory, particularly feminist theory, has produced some of the most extensive and influential work on gender, we will spend more time exploring its key frameworks and contributions.

Patriarchy and the Hierarchies of Gender

One of the central concepts in feminist theory is patriarchy, which refers to a social system where men, as a group, tend to hold greater power and influence in areas such as politics, the economy, and cultural leadership. This system often privileges traditionally masculine traits and roles, while limiting the visibility and value of those associated with femininity. Sociologists emphasize that patriarchy is not just about individual men having more authority. Instead, it’s about how institutions and cultural norms consistently produce unequal outcomes based on gender.

Importantly, scholars point out that not all men benefit equally from these systems. Those who best align with dominant ideals of masculinity tend to receive the greatest rewards. These patterns are not seen as biologically inevitable, but as socially constructed, shaped by historical and cultural forces. While this framework is a core part of feminist theory, it is one of several perspectives used to understand how gender operates in society.

Hegemonic Masculinity and Emphasized Femininity

Not all expressions of masculinity or femininity are treated equally in society. Some are praised and seen as “normal,” while others are pushed to the margins. Sociologist Raewyn Connell, in her book Masculinities (1995), introduced the idea of hegemonic masculinity to explain how certain traits associated with men become culturally dominant. This dominant form of masculinity often includes being strong, emotionally controlled, competitive, and successful, especially in careers or leadership roles.

Hegemonic masculinity is not about individual men being aggressive or powerful on their own. Instead, it refers to a set of ideals that society tends to reward. These ideals shape how men are expected to behave and influence who is seen as a leader, a protector, or even a role model. For example, a man who is assertive and ambitious at work might be praised for having “leadership qualities,” while a man who is more emotional or nurturing may not be taken as seriously.

Connell also described the idea of emphasized femininity, which refers to the ideal traits that are often expected of women. These traits include being nurturing, gentle, emotionally expressive, and physically attractive. Emphasized femininity tends to support and complement hegemonic masculinity. In other words, women are often expected to play supportive roles rather than be in positions of authority themselves.

These two ideas—hegemonic masculinity and emphasized femininity—help explain why society often places men and women into certain roles and why those roles are not valued equally. Traits associated with masculinity are often linked to power and leadership, while traits associated with femininity are linked to care and support. This does not mean that all men or all women fit these patterns, but the social expectations remain strong and can shape how people are treated in school, at work, and in the media.

It is important to recognize that these ideals are not fixed or natural. They are learned, reinforced, and often change over time. Understanding how they work allows us to think critically about gender and why some behaviors are encouraged while others are discouraged. It also opens the door for more flexible and inclusive ways of being ourselves, regardless of our gender.

Policing Gender: Everyday Enforcement

While society has broad ideas about what it means to be masculine or feminine, these expectations are not just enforced through institutions like school or media. They are also maintained in our day-to-day interactions—through teasing, judgment, and peer pressure. This everyday form of enforcement is often subtle, but it plays a powerful role in shaping how people express their gender.

Sociologist C. J. Pascoe, in her ethnographic study Dude, You’re a Fag (2007), explored how teenage boys in a high school used insults and behavior to police one another’s masculinity. Pascoe found that the word “fag” was not always used to suggest that someone was gay. Instead, it was often used to mock boys who acted in ways that were seen as too feminine—such as being emotional, not enjoying sports, or caring about how they looked.

This kind of name-calling was not just casual teasing. It worked as a form of social control, teaching boys what kinds of behaviors were acceptable if they wanted to be seen as “normal” or masculine. Boys who did not conform to these expectations often felt pressure to change how they acted in order to fit in and avoid being bullied.

The process of “policing” gender is not limited to boys or schools. It can happen in families, friend groups, workplaces, and even online. A girl who is told she is “too bossy” for speaking up in class, or a boy who is mocked for crying, both experience this pressure. These everyday reactions remind people—often without anyone even realizing it—that there are “rules” for how to behave based on gender.

What Pascoe’s research shows is that gender is not just a personal identity. It is also a performance that is watched, judged, and corrected by others. This helps explain why many people feel pressure to hide certain parts of themselves or act in ways that do not feel fully authentic. Policing gender reinforces narrow ideas about what it means to be a man or a woman and makes it harder for people to express themselves freely.

The Double-Bind in Leadership

Even as more women enter the workforce and take on leadership roles, they often face a unique challenge that many men do not: the double bind. This term describes how women are frequently caught between conflicting expectations. If they are warm and nurturing, they may be seen as likable but not strong enough to lead. If they are assertive and confident, they might gain respect but be viewed as unfeminine or too aggressive.

Sociologist Alice Eagly has studied this dynamic in depth through her research on leadership. She found that people often associate strong leadership with qualities like decisiveness, confidence, and independence, which are traditionally linked with masculinity. At the same time, women are expected to be collaborative, supportive, and modest. As a result, women leaders are often judged more harshly than their male counterparts, no matter how they behave.

This tension helps explain the persistence of the glass ceiling, a term used to describe the invisible barriers that prevent women from advancing into top leadership positions. Even when women have the education, experience, and skills for executive roles, they are still underrepresented in positions of power. Part of the reason is that the qualities typically rewarded in leadership are more often encouraged in men and criticized in women.

Another version of this double standard is the motherhood penalty, a term coined by sociologist Joan C. Williams. This refers to the ways in which working mothers are often seen as less competent or committed to their jobs. Studies have shown that mothers are more likely to be passed over for promotions, offered lower salaries, or assumed to be less available, even when their performance is the same as others. Fathers, on the other hand, often receive a boost at work, sometimes referred to as the fatherhood bonus, because they are seen as more stable and responsible.

Imagine two employees, one a man and one a woman, both returning to work after having a child. The man might be praised for balancing work and family, while the woman might be questioned about her availability or long-term commitment. These subtle but powerful assumptions affect how women advance in the workplace and contribute to the ongoing gender gap in leadership and pay.

The double bind and the motherhood penalty reflect broader social ideas about gender roles, especially around leadership and caregiving. They highlight how professional expectations are still shaped by traditional views of masculinity and femininity. Understanding these patterns is key to creating more fair and supportive environments, where people are evaluated based on their skills and performance rather than assumptions about gender or family roles.

Intersectionality and the Matrix of Domination

To fully understand gender inequality, it is important to recognize that gender does not operate in isolation. People experience gender in different ways depending on their race, class, sexuality, ability, and other aspects of identity. This idea is captured by the concept of intersectionality, first introduced by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989. Crenshaw used the term to explain how Black women often face overlapping forms of discrimination that cannot be understood by looking at race or gender alone. Instead, these systems of oppression intersect to create unique experiences.

Sociologist Patricia Hill Collins built on this idea in her book Black Feminist Thought (1990), introducing the concept of the matrix of domination. Collins explains that power and inequality are organized across multiple axes, including race, class, gender, and sexuality. These systems do not operate separately but are interconnected, shaping the social experiences of individuals in complex ways. For example, a white woman and a Black woman may both experience sexism, but the way that sexism is expressed, and the resources they have to navigate it, may be very different due to their racial and social backgrounds.

Intersectionality helps us move away from generalizations. It asks, Whose experience are we talking about? A white woman and a Black woman may both face sexism, but their experiences—and how they are treated in workplaces, schools, or healthcare systems—can be very different because of how race and gender intersect. A queer Latina woman in a low-income job, for instance, may face challenges tied not just to gender, but also to language, immigration status, and economic precarity.

This framework also helps explain why certain groups, such as Black trans women or Indigenous women, face particularly high levels of violence, discrimination, and exclusion. These experiences are not about comparing who is “more” or “less” oppressed. Rather, intersectional theory helps us understand that inequality works through multiple pathways. It’s not a competition. Instead, it’s a call to pay attention to how social systems operate differently for different people.

In classrooms, workplaces, healthcare, and beyond, intersectionality encourages a deeper and more accurate understanding of inequality. It reminds us that effective solutions require looking at the whole picture, not just one part of someone’s identity. By listening to those most impacted by overlapping inequalities, we can begin to create more inclusive and responsive systems for everyone.

***

Taken together, conflict theory and feminist theory provide a powerful framework for understanding how gender operates as a system of power that shapes access to resources, status, and recognition. These perspectives highlight how patriarchy privileges certain forms of masculinity while marginalizing femininity and those who do not conform to dominant gender norms.

Concepts such as hegemonic masculinity, emphasized femininity, the double bind, and intersectionality help illustrate how social institutions and cultural expectations reinforce inequality, while also showing that gender is experienced differently depending on one’s race, class, sexuality, and other identities. Importantly, intersectionality is not about comparing who is “most oppressed,” but about recognizing how multiple systems of power combine to shape unique experiences, such as those of Black trans women or Indigenous women. Rather than offering simple solutions, feminist theory encourages us to ask critical questions about how gender is structured and how it can be transformed.

While much of this work has focused on the disadvantages women and marginalized groups face, sociologists are also turning their attention to the challenges facing boys and men in a changing society.

Flipping the Narrative: Challenges Faced by Men in Modern Society

While previous discussions have highlighted how hegemonic masculinity grants men power and privilege in many societal contexts, it’s important to acknowledge that not all men benefit equally from these systems. In fact, many men, especially in recent decades, have faced serious challenges that often go overlooked in discussions about gender. Richard Reeves, in his book Of Boys and Men, shifts the focus to the growing crises affecting men in education, the workforce, and personal identity. Reeves argues that, although patriarchy continues to position men in dominant roles, modern societal shifts are disproportionately affecting the well-being of many boys and men.

In many Western countries, including the United States, girls consistently outperform boys in standardized tests of reading and writing. As Reeves notes, this trend has left boys struggling to compete in an economy that increasingly values higher education and strong communication skills. Without these foundational skills, men are finding it harder to navigate the modern labor market.

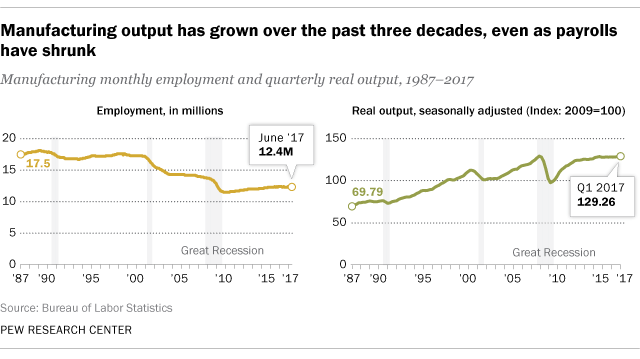

Declining Male Participation in the Workforce

Reeves also highlights the issue of declining male participation in the workforce. As industries like manufacturing and manual labor decline due to automation and globalization, many men have been displaced from jobs that once provided stable incomes and a clear sense of identity. The shift toward a service-based economy has left many men, particularly those without higher education, struggling to find work. This economic dislocation has contributed to rising rates of unemployment and underemployment, especially among working-class men.

This trend is not just about job loss but about a broader identity crisis for men, many of whom were traditionally socialized to see themselves as the primary breadwinners. With fewer stable, well-paying jobs available to men without college degrees, many feel disconnected from the roles that once gave them a sense of purpose. The opioid crisis in the United States, which disproportionately affects men, is often linked to this loss of economic stability and direction. Rising rates of “deaths of despair,” which include drug overdoses, suicides, and alcohol-related diseases, highlight how deeply these economic shifts are impacting men’s mental and physical well-being.

Mental Health and the Crisis of Masculinity

In addition to economic challenges, Reeves discusses the mental health crisis affecting men. Although men are less likely than women to be diagnosed with mental health disorders, they are far more likely to die by suicide. Men often hesitate to seek help for mental health issues due to societal expectations that they should remain strong, stoic, and emotionally restrained—traits aligned with hegemonic masculinity. This emotional suppression can lead to untreated mental health problems, with devastating consequences.

Fatherhood and Changing Gender Roles

Another issue Reeves examines is the evolving role of fatherhood. In the past, men were often seen as distant authority figures, but today’s fathers are expected to be more emotionally involved in parenting. While this shift represents progress, many men struggle to balance these new expectations with their traditional role as providers. Additionally, the rise of single-parent households and the decline of marriage have left many men disconnected from their children, contributing to feelings of alienation and helplessness.

In countries like Sweden and Norway, policies such as paternity leave have encouraged men to take a more active role in parenting, showing how societal structures can support changing gender roles (Source). Reeves argues that policies like these, which promote father involvement, are crucial for addressing the disconnect many men feel in their roles as fathers. When men are encouraged to play a more active role in their children’s lives, they report greater life satisfaction, but societal norms and workplace policies still often treat caregiving as primarily a woman’s responsibility.

Reimagining Masculinity

Richard Reeves’ reimagining of masculinity goes beyond simply advocating for men to embrace emotional expression and vulnerability. His framework challenges the deeply ingrained notion of hegemonic masculinity, which prizes traits like toughness, stoicism, and competitiveness, and calls for a broader, more inclusive definition of what it means to “be a man.” Reeves argues that these traditional expectations are not only restrictive but also damaging, as they prevent men from fully engaging with their emotions and limit their opportunities for personal growth. By redefining masculinity to include qualities such as care, emotional intelligence, and collaboration, Reeves believes men can lead healthier, more balanced lives.

A central part of Reeves’ proposal is encouraging men and boys to explore careers in caregiving professions such as nursing, teaching, and social work—fields traditionally dominated by women. This shift, he argues, would help break down gendered divisions of labor, which have long constrained both men and women. For men, entering these professions could offer a more diverse set of opportunities and a way to redefine success beyond the confines of traditional male-dominated fields like business or engineering. For women, this could alleviate the cultural pressure to be the sole providers of emotional labor and caregiving, fostering a more equitable division of responsibilities across genders.

Reeves also critiques the societal structures that continue to reward traditional masculinity. In many workplaces and educational settings, assertiveness, competition, and emotional restraint are often valued over collaboration and empathy—qualities that might be more commonly associated with femininity but are beneficial to everyone. By reshaping our cultural expectations of masculinity, Reeves suggests that both men and women would benefit from a more balanced, less rigid understanding of gender roles. This restructuring could reduce the pressures on men to conform to outdated ideals while allowing them to express themselves more fully.

Ultimately, Reeves calls for a holistic redefinition of masculinity that embraces diversity and emotional complexity. By promoting flexibility in career choices, encouraging emotional openness, and dismantling the rigid structures of hegemonic masculinity, Reeves envisions a society where men are not bound by harmful stereotypes but are free to express a fuller range of human traits. This would not only benefit individual men but also create a more inclusive and equitable society overall.

Conclusion

Throughout this module, we have seen that sex and gender are not simply private matters of biology or identity but are deeply social phenomena. From the functionalist view of gender roles as stabilizing family structures, to symbolic interactionism’s emphasis on everyday performances, to feminist theories that foreground power and inequality, sociologists show that gender is always embedded in cultural norms and institutional practices. Concepts such as patriarchy, hegemonic masculinity, emphasized femininity, and intersectionality reveal how gender inequality is produced and maintained, while also pointing to the ways individuals and groups contest these norms.

At the same time, this exploration highlights that gender is not just about the marginalization of women. Shifts in the economy, family life, and cultural expectations have created new challenges for men as well, raising important questions about how masculinity is defined and lived today. Richard Reeves’s work underscores that gender norms can constrain men just as they constrain women, and that reimagining masculinity is an essential part of building a more equitable society.

Taken together, these perspectives encourage us to think critically about the rules and expectations that shape gendered life. They remind us that gender is not fixed, natural, or inevitable but socially constructed, contested, and changeable. By questioning how gender operates across institutions and identities, sociology opens space for imagining new possibilities—societies where people are not limited by rigid roles, but free to express themselves and share in resources, opportunities, and recognition on more equal terms.

Key Concepts

Agender: A person who does not identify with any gender, or identifies as having no gender.

Biological Essentialism: The belief that gender differences are rooted in biological differences between men and women, and that these differences are natural, unchangeable, and fixed.

Cisgender: A term for individuals whose gender identity aligns with the sex they were assigned at birth.

“Doing Gender”: A concept introduced by sociologists West and Zimmerman, meaning that gender is not something we are, but something we do in everyday interactions based on societal expectations.

“Double Bind”: A situation where a person is faced with two conflicting demands, with no correct or acceptable answer. Women often face this in leadership, where they are criticized for being too feminine or too masculine.

Emphasized Femininity: A form of femininity that is defined by compliance with the gender roles that serve the interests of men, often emphasizing traits like passivity, nurturing, and beauty.

Expressive Role: In Talcott Parsons’ functionalist theory, the role typically assigned to women, focusing on emotional support, caregiving, and maintaining harmony within the household.

Feminism: A movement and theoretical perspective that advocates for gender equality and challenges systems that maintain male dominance and female subordination.

Gender: A social construct that refers to the roles, behaviors, and identities society associates with being male or female.

Gender-Fluid: A gender identity where an individual’s gender changes over time, fluctuating between different identities.

Gender Performativity: The idea that gender is not a stable identity but is continuously enacted through repeated behaviors shaped by cultural norms.

Glass Ceiling: The invisible barriers that prevent women and minorities from advancing to top leadership positions despite their qualifications.

Hegemonic Masculinity: The dominant form of masculinity in a society, which emphasizes traits like toughness, assertiveness, and emotional restraint.

Hijra: A legally recognized third gender in South Asia, often including people assigned male at birth who adopt feminine gender roles, but the community can include a variety of gender expressions.

Instrumental Role: In Talcott Parsons’ functionalist theory, the role typically assigned to men, focusing on providing for the family, making decisions, and representing the household in the public sphere.

Intersectionality: A framework for understanding how overlapping identities (race, class, gender, sexuality, etc.) shape unique experiences of oppression and privilege.

Matrix of Domination: The interlocking systems of oppression, such as race, class, gender, and sexuality that together structure inequality.

Motherhood Penalty: The economic and career disadvantages that women experience when they have children, including lower wages and fewer promotions.

Nonbinary: A gender identity that doesn’t fit strictly into the categories of male or female.

Patriarchy: A social system where men hold primary power and dominate roles in leadership, authority, and control of property.

Sex: The biological and physiological characteristics that define humans as male, female, or intersex, typically based on chromosomes, hormones, and reproductive organs.

Social Constructionism: The theory that gender roles and identities are created and maintained by societal norms and expectations rather than biology.

Transgender: A term for individuals whose gender identity does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth.

Two-Spirit: A term used by some Indigenous North American cultures to describe a person who embodies both masculine and feminine qualities, often seen as having a unique social or spiritual role.

Reflection Questions

- How do scientific and sociological perspectives complicate binary views of sex and gender, and what factors contribute to understanding them as fluid rather than fixed categories?

- How does Talcott Parsons’ functionalist theory of instrumental and expressive roles explain the division of labor within families, and what are the strengths and limitations of this perspective when applied to contemporary society?

- How does the concept of intersectionality, developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw and expanded by Patricia Hill Collins, help explain why some groups—such as Black trans women or Indigenous women—face particularly high levels of discrimination and exclusion?

- How does C.J. Pascoe’s research on masculinity in high school illustrate the enforcement of hegemonic masculinity, and what does it reveal about the social costs of nonconformity?

- How does Richard Reeves’ analysis of men’s challenges in education, work, and family life complicate the idea that patriarchy benefits all men equally? What solutions does he propose for reimagining masculinity in a changing society?