Table of Contents

- Learning Objectives

- Introduction

- Race and Ethnicity: Understanding the Differences

- The Modern Invention of Race

- The Shift From Biological Race to Social Construction

- Different Forms of Racism: Individual vs. Structural Racism

- W.E.B. Du Bois: Pioneering Theories of Race and Identity

- Debating Colorblindness: Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and Coleman Hughes

- Conclusion

- Key Concepts

- Reflection Questions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, students will be able to:

- Differentiate between race and ethnicity, defining each sociologically and explaining how they are constructed, perceived, and used in social classification.

- Explain how race is socially constructed, not biologically determined, using historical examples from scientific racism, the U.S. Census, and sociological theory.

- Analyze how self-identity and social identity can come into conflict, using case studies like Rachel Dolezal to explore how race is enforced by societal perception.

- Trace the historical emergence of modern racial categories, including how colonialism, religious ideology, and pseudoscience shaped racial hierarchies.

- Apply major theoretical frameworks to the study of race, including:

- Stuart Hall’s representation theory,

- Étienne Balibar’s linkage of race to nationalism and state power,

- Omi and Winant’s racial formation theory,

- W.E.B. Du Bois’s concepts of double consciousness and the psychological wage.

- Distinguish between individual and structural racism, providing examples of how each operates and how they reinforce one another in everyday life and institutions.

- Evaluate the impact of structural racism in specific domains such as wealth accumulation, education, criminal justice, and environmental health.

- Interpret contemporary debates around colorblindness and race-consciousness, comparing the perspectives of Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and Coleman Hughes on how best to achieve racial equity.

- Connect race to systems of power and privilege, showing how racial categories function to structure opportunity, inequality, and institutional arrangements.

- Critically reflect on how sociological analysis of race and ethnicity can inform activism, policy, and the pursuit of a more equitable and inclusive society.

Introduction

In June 2015, Rachel Dolezal, a civil rights leader and president of the Spokane, Washington chapter of the NAACP, found herself at the center of a national controversy. Dolezal, who had publicly identified and lived as a Black woman for years, was revealed to have been born to white parents. This disclosure, made by her own family, ignited a media firestorm and a fierce public debate over the nature of race and identity in America.

Dolezal’s story raises critical questions: Can someone choose their racial identity? What happens when self-perception conflicts with societal perception? For years, Dolezal’s self-identity was that of a Black woman, a role she embraced both personally and professionally. However, when her white parentage was made public, her social identity—the racial category society assigned to her—shifted drastically. Many accused her of deception and cultural appropriation, and she ultimately resigned from her NAACP position.

This incident reveals the tension between self-identity and social identity. Self-identity is shaped by personal beliefs, while social identity reflects how society categorizes individuals based on traits like race, gender, and class. In Dolezal’s case, her self-identified race clashed with society’s classification, resulting in severe social and professional consequences.

Dolezal’s story exposes a deeper truth about race in America: while race is a social construct, it has real, tangible effects. Though not biologically determined, race profoundly shapes people’s lives—from opportunities to social treatment. Dolezal’s experience underscores how powerfully social constructions operate. Crossing racial boundaries, especially when self-identity conflicts with social identity, can lead to significant personal and public repercussions.

The Dolezal controversy serves as a vivid reminder that race, though not based in biology, has immense weight in shaping lived experiences. Sociologists study race and ethnicity precisely because these constructs affect societal organization, institutional function, and the distribution of power and privilege. Through Dolezal’s case, we see how race shapes both identity and societal perception. As we move through this chapter, we will examine the ways race and ethnicity influence social structures, perpetuate inequality, and illuminate the dynamics of power and social stratification.

Race and Ethnicity: Understanding the Differences

Like sex and gender, many people often conflate race and ethnicity, assuming that both terms refer to the same characteristics. However, these two concepts are distinct and carry different meanings, especially when examined through the lens of sociology. Understanding their differences is crucial to unpacking the ways societies categorize individuals and create hierarchies that impact people’s lives in tangible ways.

Race refers to a social classification based on perceived physical characteristics, such as skin color, facial features, or hair texture. These characteristics are used to group people into broad categories, like “Black,” “White,” “Asian,” or “Latino.” While many people assume race is rooted in biology, it is actually a social construct—an idea created by societies to categorize and differentiate people based on appearance. The categories we use to define race have shifted over time and vary across cultures, highlighting that race is not a natural or fixed reality but a way societies organize individuals. For example, someone in the United States might be classified as “Black” based on their skin color, but in Brazil, where racial categories are understood differently, they might be classified as “Pardo” (mixed-race). This variability shows that race is shaped by cultural and historical contexts rather than biology.

Ethnicity, in contrast, refers to a group’s shared cultural practices, beliefs, and heritage. Ethnic groups often have common language, religion, traditions, or historical experiences. Unlike race, which is often assigned externally, ethnicity is typically self-identified—individuals identify with an ethnic group based on shared cultural ties. For instance, someone may identify as ethnically Irish because they participate in Irish cultural traditions, or as Han Chinese because they share the language and customs of that ethnic group.

An important example of the difference between race and ethnicity can be seen within the Latino community. People who identify as Latino share a cultural connection to Latin America, which is an ethnicity, not a race. A Latino person might identify racially as Black, White, Indigenous, or mixed, but they belong to the same ethnic group because of their shared cultural background. This demonstrates that ethnicity is more about cultural identity, while race is based on physical traits that society assigns meaning to.

Both race and ethnicity are social categories that shape how individuals understand themselves and how they are perceived by others, but they are not the same. An easy way to remember this is that race focuses on external physical characteristics, while ethnicity focuses on shared cultural heritage.

While ethnicity is extremely important in the study of sociology, we will instead focus on the historical ways race has been socially constructed and the very real consequences that stem from that construction.

The Modern Invention of Race

Before the concept of race as we understand it today emerged, societies often categorized and differentiated people based on factors like religion, geography, and social status. In medieval Europe, for example, individuals were grouped according to their religion—Christians, Jews, and Muslims—or their place of origin. Social stratification was largely based on class and status rather than skin color. Ancient civilizations like the Greeks and Romans also distinguished people by their cultural practices or geographical location rather than any fixed notion of racial difference. These early forms of differentiation were fluid and did not correspond to the rigid racial categories that would later develop.

The concept of race as a rigid, biological classification emerged during the 18th and 19th centuries, coinciding with the rise of biological sciences and the expansion of European colonialism. During this period, pseudoscientific theories sought to classify human beings into distinct racial groups based on perceived physical traits such as skin color, skull shape, and hair texture. These racial categories were arranged in hierarchical orders, with white Europeans positioned at the top and other races deemed inferior.

A notorious example of this pseudoscience was the work of Samuel George Morton, a 19th-century American physician. Morton collected hundreds of skulls from different racial groups and claimed that skull size correlated with intellectual ability. He concluded that Europeans had the largest skulls—and were therefore the most intelligent—while Africans had the smallest skulls, supposedly signifying intellectual inferiority. Although Morton’s methods were deeply flawed, his work was widely accepted at the time and used to legitimize slavery, colonialism, and racial segregation. This biological view of race reinforced the idea that racial hierarchies were natural and immutable.

However, religious myths also played a significant role in shaping these racial ideologies. The Sons of Ham myth, derived from the Bible, became a popular justification for the enslavement of Africans. According to this myth, Ham, one of Noah’s sons, was cursed by his father, and his descendants were condemned to serve the descendants of his brothers. Over time, this story was interpreted to suggest that Ham’s descendants were Africans, and that the curse justified their enslavement. This myth, like Morton’s pseudoscientific theories, provided a cultural and divine rationale for racial oppression.

The Shift From Biological Race to Social Construction

For much of modern history, race was widely considered a biological reality, with certain groups viewed as fundamentally different or superior to others based on physical characteristics like skin color, hair texture, and facial features. This belief in race as a biological determinant served as a foundation for racial hierarchies, scientific racism, and oppressive practices throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, by the mid-20th century, scientific advancements, social movements, and new theoretical perspectives began challenging this notion, shifting the understanding of race from a biologically fixed trait to a socially constructed category.

One of the major scientific developments that helped to dismantle the idea of race as a biological reality was the Human Genome Project. Completed in 2003, this international research effort mapped the entire human genome, revealing that humans share 99.9% of their genetic material, regardless of race. Physical differences among humans, such as skin color or hair texture, account for only a tiny fraction of genetic variation, meaning these differences do not represent distinct biological divisions. These findings affirmed that race has no genetic basis, debunking the pseudoscientific racial hierarchies of the past and shifting the focus toward understanding race as a social and cultural construct.

However, before the Human Genome Project, sociological thinkers like Étienne Balibar, Stuart Hall, and later, Michael Omi and Howard Winant, were already instrumental in advancing this new perspective on race. Together, they reframed race as a category shaped by historical, social, and political forces rather than biology. Each theorist approached the social construction of race in unique ways, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of how race operates as a tool for organizing societies and maintaining power structures.

Theoretical Foundations: Hall, Balibar, Omi, and Winant

Stuart Hall (1932-2014), a British-Jamaican cultural theorist, was a leading voice in examining how race is constructed through language, symbols, and media representations. Hall’s key work on this topic is found in Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (1997), which explored how media and cultural narratives shape public perceptions of race and reinforce social hierarchies. Rather than seeing race as an objective reality, Hall examined how racial identities are created and maintained through cultural practices and systems of representation, such as media portrayals and popular culture. Hall’s work emphasized that race is inseparable from the social meanings assigned to it, and he showed how these meanings are often used to reinforce power structures, determining who holds privilege and who faces marginalization.

Étienne Balibar (1942-Present), a French philosopher, extended Hall’s work by exploring how race is closely tied to national identity, colonial histories, and state power. In his influential book Race, Nation, Class (1988), co-authored with sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein, Balibar argued that race operates as a cultural category deeply connected to the legacies of colonialism and the global economy. For Balibar, race is often used as a tool to exclude groups deemed “outsiders” and to justify unequal power relations. He showed how racial categories are linked to social and economic interests, with governments and institutions using these categories to control populations, maintain social order, and secure economic dominance. By highlighting these connections, Balibar emphasized that race is constructed and maintained through the intersection of cultural, political, and economic forces, which often serve to uphold national and imperial interests.

Building on the ideas of Hall and Balibar, sociologists Michael Omi (1951-Present) and Howard Winant (1946-Present) introduced a framework for understanding the shift from a biologically based concept of race to one that is socially constructed, through their racial formation theory. In their influential work Racial Formation in the United States (1986), Omi and Winant argued that race is a dynamic social construct shaped by historical events, political movements, and economic interests, rather than a fixed biological trait. They defined racial formation as the process by which racial categories are created, inhabited, transformed, and sometimes even eliminated. According to Omi and Winant, race is continuously redefined by social and political forces rather than remaining a stable characteristic. A central concept within racial formation theory is the idea of racial projects, or efforts—often through laws, policies, or cultural movements—that define and organize racial identities and hierarchies. For example, Jim Crow laws served as racial projects aimed at maintaining white supremacy, while the Civil Rights Movement represented a racial project designed to challenge racial hierarchies. Through racial projects, society assigns meaning to race, making it a tool for organizing power and social structures.

The Implications of Socially Constructed Race

Together, Hall, Balibar, and Omi and Winant offer a powerful framework for understanding race as a social construct, revealing that race is not an inherent or biological reality but a category created and maintained by social, political, and economic forces. This shift in understanding allows us to see race as a tool used historically to justify exploitation, control populations, and sustain inequality, while also showing that race is flexible and can be redefined by cultural and political movements. For instance, the history of the U.S. Census reflects the socially constructed nature of race; racial categories have changed multiple times over the years to reflect shifting social and political priorities. In early censuses, categories like “Mulatto” and “Quadroon” were used to distinguish between people of mixed racial heritage. In 1930, “Mexican” was classified as a racial category, only to be removed later. Today, the U.S. Census allows individuals to select multiple races, highlighting the evolving and fluid nature of racial categories (Source).

This shift from biological determinism to social construction reshapes our understanding of race, allowing us to see it as a social invention rather than a natural fact. By moving away from biological explanations, these theorists encourage a focus on how race operates within social hierarchies and as a means of distributing power. This perspective makes it clear that while race may not be biologically real, its social consequences are profound. Racial categories have been used to create and sustain inequalities that persist in modern institutions and everyday interactions, making race an integral part of social structures.

Different Forms of Racism: Individual vs. Structural Racism

Racism can be broadly defined as a system of beliefs, practices, and institutional structures that create and maintain inequality by treating certain racial or ethnic groups as inferior to others. It operates on multiple levels, impacting individuals, groups, and entire societies. Racism encompasses not only the prejudiced attitudes and discriminatory actions of individuals but also the ways in which societal systems and institutions perpetuate racial inequalities over time. Sociologists distinguish between individual racism, which includes prejudiced behaviors or attitudes directed at others based on race, and structural racism, which refers to the broader social patterns and institutional practices that create and sustain racial disparities. While individual racism focuses on the actions and attitudes of specific people, structural racism emphasizes the legacies and systems that affect entire racial groups, often irrespective of individual intent. Together, these layers of racism work to reinforce social hierarchies and restrict opportunities for marginalized groups, making racism a complex, deeply embedded force in society.

Individual Racism

Individual racism refers to the attitudes, actions, and beliefs that individuals may hold or express that perpetuate racial inequality. It includes behaviors and mindsets that consciously or unconsciously devalue people based on race. This type of racism manifests in several forms:

- Prejudice, Discrimination, Stereotyping, and Xenophobia: These forms of racism all relate to biased views or treatment of individuals based on race or ethnicity. Prejudice involves holding negative attitudes toward people of certain races, while discrimination is the act of unfairly treating someone based on their race. Stereotyping reduces entire racial or ethnic groups to simplified, often negative traits, such as assuming all Black individuals are dangerous or that all Asian Americans are good at math. Xenophobia involves a fear or distrust of people from other countries, which can lead to hostility toward immigrants or foreign-born individuals. For example, assuming that immigrants are “taking jobs” from native-born citizens is a xenophobic stereotype that can drive exclusionary behavior. Together, these attitudes and actions contribute to a culture where people are unfairly judged and treated based on their racial or ethnic background.

- Microaggressions: Microaggressions are subtle, often unintentional, comments or actions that reflect underlying racial bias. For instance, telling an Asian American, “Your English is so good!” assumes that the person is a foreigner, despite being fluent in English. Microaggressions may seem minor in isolation, but they can accumulate over time and create a hostile environment for those who experience them regularly. Examples include comments like, “You don’t act Black,” which implies that there is a single way to “act” based on one’s race.

- Overt Racism and Racial Violence: Overt racism includes hate speech, violent acts, and participation in hate groups. This type of racism is explicit and often aggressive, including the actions of groups like the Ku Klux Klan, neo-Nazi organizations, or individuals committing hate crimes. Data from the FBI reveals a disturbing trend: in 2020, hate crimes against Black individuals rose 49% compared to 2019, reaching their highest level in over a decade, reflecting a broader increase in racial violence. Hate crimes targeting Asian Americans also surged 77% between 2019 and 2020, largely fueled by xenophobic rhetoric during the COVID-19 pandemic (Source). These statistics highlight the continued presence of overt racism and the increase in racially motivated violence over recent years.

Individual racism includes both subtle and overt forms, from microaggressions to racially motivated violence, that reinforce social hierarchies based on race. These actions collectively contribute to an environment where certain groups are systematically devalued and marginalized.

Structural Racism (Also Known as Institutional, Systemic or Societal Racism)

Structural racism refers to the policies, practices, and institutional structures that maintain racial inequality across generations. Structural racism does not depend on individual attitudes; rather, it is embedded in societal systems that affect people’s opportunities and resources. Understanding structural racism can be challenging because it is often less visible than individual acts of prejudice, but it operates on a much larger scale.

Key elements of structural racism include:

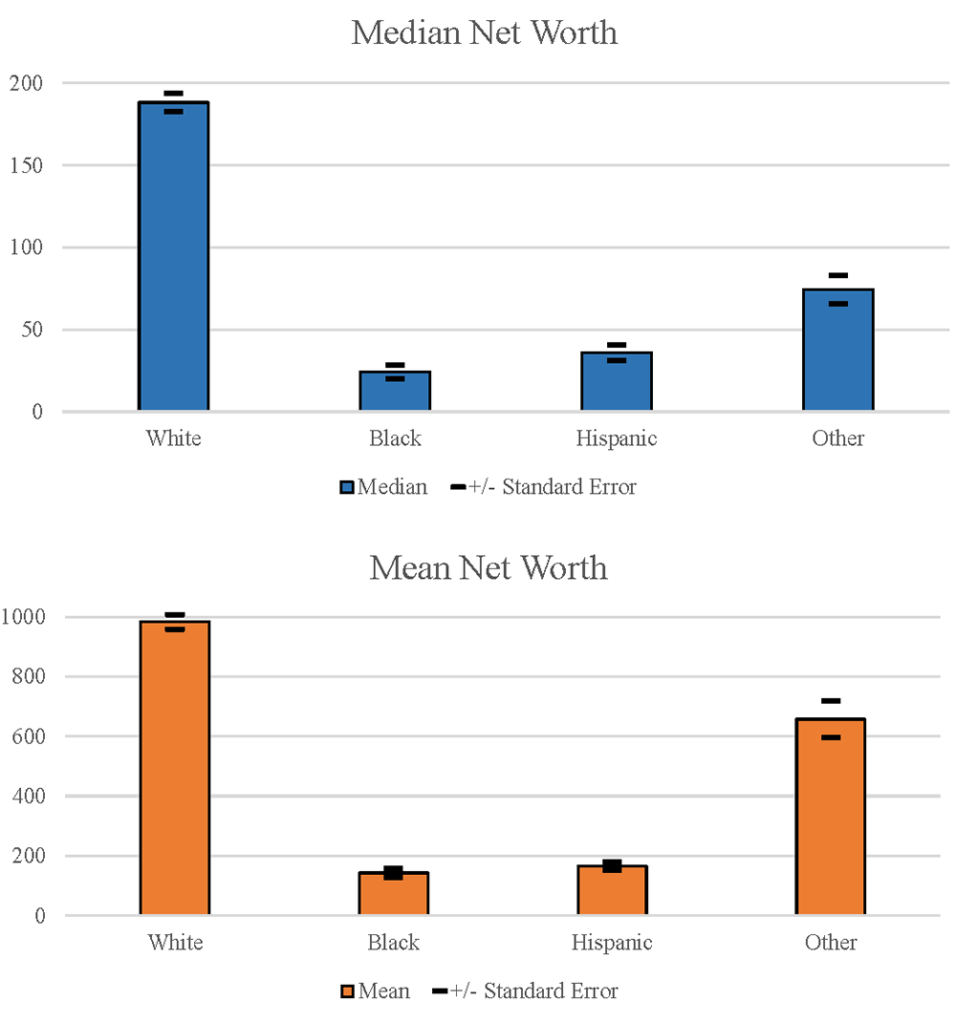

- Legacy of Discriminatory Policies and the Wealth Gap: Structural racism is also built on the long-term impacts of discriminatory policies, one of the most well-known examples being redlining. Redlining was a government policy beginning in the 1930s in which the federal government and banks created maps that rated neighborhoods for their “desirability” based on racial demographics. Predominantly Black or immigrant neighborhoods were outlined in red, marked as risky, and systematically denied access to home loans and other financial services. The effects persist today, as the average Black household has only about 12.7% of the wealth of the average white household ($24,100 compared to $188,200, respectively) (Source). Formerly redlined areas continue to face economic challenges, lower property values, and underfunded schools, illustrating how historic discrimination contributes to ongoing racial wealth disparities.

- Criminal Justice System: The criminal justice system is a significant area where structural racism operates, as analyzed by Michelle Alexander in her book The New Jim Crow. Black Americans are incarcerated at five times the rate of white Americans, despite similar rates of drug use across racial groups. Furthermore, Black men specifically face a 1 in 3 chance of being imprisoned in their lifetime, compared to a 1 in 17 chance for white men (Source). These disparities reflect policies, such as the War on Drugs, that have disproportionately targeted Black and Latino communities, leading to lifelong impacts on employment, housing, and voting rights. Structural racism in the criminal justice system thus creates a cycle where people of color are systematically disadvantaged and disproportionately affected by punitive policies.

- Environmental Racism: Environmental racism refers to the disproportionate impact of environmental hazards on communities of color. Studies show that Black Americans are 75% more likely than white Americans to live near facilities that produce hazardous waste, leading to higher risks of asthma, cancer, and other health issues (Source). Additionally, Black and Latino neighborhoods are more likely to experience air pollution and lack access to clean water, as seen in the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, where a predominantly Black community faced years of lead-contaminated water (Source). Environmental racism is a powerful example of how structural inequalities extend to public health and quality of life for marginalized groups.

- Education and Employment Inequities: Structural racism also impacts access to quality education and employment opportunities. Schools in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods often receive less funding, resulting in larger class sizes, fewer resources, and less experienced teachers (Source). For instance, the U.S. Department of Education found that predominantly non-white school districts receive $23 billion less in funding than predominantly white districts despite serving the same number of students (Source). In the job market, studies show that job applicants with “ethnic-sounding” names are less likely to receive callbacks compared to applicants with traditionally white-sounding names, even when their qualifications are identical (Source). These disparities create barriers for marginalized groups, perpetuating cycles of poverty and limiting upward mobility.

Structural racism focuses on the impact rather than the intent of policies or practices. While individuals may not hold racist beliefs or act on them personally, they still participate in and benefit from systems that disproportionately disadvantage certain racial groups. Addressing structural racism requires recognizing these deeply embedded inequalities and implementing changes to policies, institutions, and practices that perpetuate them.

The Interplay of Individual and Structural Racism: Intent, Impact, and Systemic Reinforcement

Individual racism and structural racism are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. Individual actions, such as microaggressions or discriminatory hiring practices, both reflect and reinforce broader systems that uphold racial hierarchies. At the same time, structural racism perpetuates the stereotypes, biases, and exclusions that drive individual prejudices and discriminatory behaviors. This relationship highlights the key distinction between intent and impact: while individual racism often reflects a person’s intent, structural racism is primarily about the impact of policies, practices, and institutions that sustain inequality over time. By addressing both forms of racism—at the individual and structural levels—society can work toward dismantling the persistent systems that perpetuate racial injustice.

W.E.B. Du Bois: Pioneering Theories of Race and Identity

https://www.youtube.com/embed/KkpH6wJ20Cg?feature=oembedModule 13, Part 04 Lecture: “W.E.B. Du Bois: Double Consciousness & the Psychological Wage,” The Online Sociologist. Video Link.

W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) was a pioneering sociologist, historian, and civil rights activist whose work redefined the study of race in America. Born in 1868, Du Bois was among the first African Americans to earn a doctorate from Harvard University and was a co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. Throughout his life, he combined rigorous academic research with a commitment to social justice, challenging racial injustices and advocating for the empowerment of Black Americans. His scholarship laid the foundation for modern sociology, particularly in the study of race and racism, and his influence can still be seen in fields ranging from sociology to political science and African American studies.

One of Du Bois’s early major contributions was his 1899 study, The Philadelphia Negro, which analyzed the lives of Black residents in Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward. This study was groundbreaking for its systematic use of statistics and data visualization, marking one of the first applications of empirical research to document the social and economic conditions of an urban Black community. By gathering and visualizing data, Du Bois demonstrated that systemic racism, not inherent deficiencies, caused social disparities—a revelation that countered prevailing stereotypes. The Philadelphia Negro set a standard for sociological research by showing how quantitative data could effectively challenge racial myths and influence public perception.

Du Bois’s work also introduced foundational theories of race, including his concept of double consciousness and his reinterpretation of Reconstruction in the 1935 book, Black Reconstruction in America. Through these contributions, Du Bois provided critical insights into the social realities of Black Americans and dismantled pervasive racial narratives.

Double Consciousness: Navigating Two Conflicting Identities

One of Du Bois’s most influential concepts is double consciousness, introduced in his 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk. Double consciousness describes the experience of African Americans living in a society that devalues them based on their race. This concept explains the internal conflict faced by Black individuals who must navigate their self-identity while also remaining acutely aware of how they are perceived by a prejudiced society.

Du Bois articulated this phenomenon as “two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings” within one person. African Americans, he argued, were forced to view themselves through their own eyes and through the lens of a society that saw them as inferior. This dual perspective created a sense of fractured identity, as Black individuals balanced their own self-perception with the stereotypes imposed upon them.

For example, consider a Black professional in the early 20th century, striving to succeed in a predominantly white workplace. Despite being qualified and ambitious, they might be aware of societal assumptions that cast them as less competent or “out of place” in professional settings. This individual may feel pride in their achievements but simultaneously experience self-consciousness, knowing that their colleagues may harbor biases or make assumptions about their abilities. This constant negotiation between their own goals and the limiting stereotypes of society is at the heart of double consciousness, underscoring the emotional toll of living in a society that imposes demeaning racial identities.

Double consciousness continues to be a valuable framework for understanding the psychological impact of systemic racism. It highlights the challenges Black Americans face in asserting their identity within a society that often denies their full humanity, revealing how racial oppression shapes both individual identities and social interactions.

Reinterpreting Reconstruction: The Psychological Wage & Challenging the “Lost Cause” Narrative

In Black Reconstruction in America (1935), W.E.B. Du Bois offered a groundbreaking reinterpretation of the Reconstruction era, challenging the prevailing “Lost Cause” narrative. The Lost Cause myth, promoted by Southern historians, romanticized the Confederacy and framed the Civil War as a fight over states’ rights rather than slavery, portraying Reconstruction as a period of chaos caused by the supposed incompetence of newly freed Black Americans. Du Bois’s work countered this view, presenting Reconstruction as a progressive attempt to create a more just and democratic society in the South, driven by the agency of freed Black Americans who advocated for labor rights, public education, and civil protections. According to Du Bois, Reconstruction was ultimately sabotaged by white supremacist violence and the economic interests of the elite, who sought to regain control by exploiting racial divisions.

A key concept Du Bois introduced in Black Reconstruction is the psychological wage, a tactic used by Southern elites to keep poor whites aligned with their interests by fostering a sense of racial superiority. While poor white laborers shared economic hardships similar to those of enslaved Black people and later freed Blacks, they were given a “psychological wage” that elevated their status above Black people. This wage took the form of social privileges, particularly in Jim Crow Laws, such as exclusive access to certain public spaces, preferential treatment by law enforcement, and the right to participate in voting and juries—rights systematically denied to Black people. Rather than receiving actual economic benefits, poor whites were encouraged to see themselves as superior, despite their own struggles, which maintained divisions between them and Black laborers. This division inhibited poor whites from recognizing shared economic interests with Black people and kept them from uniting in solidarity against the wealthy elite, who ultimately benefited from the racial divide.

In modern times, the psychological wage can be seen in examples such as racial resentment stoked during times of economic insecurity. For instance, policies and narratives that emphasize immigrants as job competitors for “real Americans” or characterize minority groups as beneficiaries of social programs, while ignoring the broader economic policies that impact all working-class people, serve as a psychological wage. This dynamic can also be observed in political rhetoric that scapegoats minority communities for issues like crime or unemployment further exploits these divisions, creating a psychological wage that obscures the structural causes of economic and social inequality.

The concept of the psychological wage, alongside Du Bois’s reinterpretation of Reconstruction, has had a lasting impact on how we understand the role of race in structuring social and economic hierarchies. By exposing how racial divisions were deliberately created to keep poor whites separated from Black individuals, Du Bois highlighted the ways race and class are intertwined in sustaining inequality. Black Reconstruction in America remains a foundational text, influencing generations of scholars and activists. Its insights into the psychological wage offer a powerful framework for examining how racial divisions continue to weaken social solidarity and perpetuate systemic inequality, underscoring the enduring relevance of Du Bois’s work in contemporary discussions of race and class.

Debating Colorblindness: Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and Coleman Hughes

The question of whether society should adopt a “colorblind” approach to race—where people and institutions treat everyone the same, regardless of race—is a deeply divisive one. Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and Coleman Hughes are two prominent voices on opposing sides of this debate, each offering different insights into how race should be handled in politics and society.

Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (1962-Present), a distinguished sociologist, is well-known for his critical analysis of colorblindness, particularly through his concept of colorblind racism. He argues in his 2003 book, Racism Without Racists, that colorblindness can actually mask ongoing racial inequalities and is a major force sustaining systemic racism. Coleman Hughes (1996-Present), on the other hand, is a writer, commentator, and author of the 2024 book, The End of Race Politics, where he argues for moving past race-conscious policies and embracing colorblindness as a way to promote unity and overcome racial divisions. This debate is important because it goes to the heart of how society should address racial inequality: Should we emphasize race in order to address disparities, or should we minimize it to achieve true equality?

Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and Colorblind Racism

Eduardo Bonilla-Silva argues that colorblindness is not the solution to racial inequality; rather, it is part of the problem. He coined the term colorblind racism to describe the modern-day form of racism that does not rely on overtly racist beliefs or language but instead works subtly, often through statements like “I don’t see race” or “We are all the same.” According to Bonilla-Silva, colorblind racism ignores the historical and structural realities that continue to produce inequality between racial groups.

In his influential book Racism Without Racists, Bonilla-Silva outlines several ways in which colorblindness can perpetuate inequality. For instance, he explains that people who claim to be colorblind often avoid conversations about race altogether, which prevents meaningful discussions about inequality and social justice. Bonilla-Silva suggests that by dismissing or minimizing race, people can unintentionally deny the real challenges faced by marginalized groups, leading to a form of denial that ultimately benefits those in power. According to Bonilla-Silva, colorblindness upholds the status quo by making it easier for people to overlook systemic issues, such as discrimination in hiring or disparities in educational resources, because they believe everyone is treated equally under a “colorblind” approach.

For Bonilla-Silva, addressing racial inequality requires explicitly acknowledging race and taking race-conscious action to address disparities. He believes that colorblindness is a barrier to social change because it prevents society from confronting the underlying causes of racial inequality. In his view, race-conscious policies, such as affirmative action, are necessary tools for dismantling systemic racism and ensuring that all racial groups have equal access to opportunities.

Coleman Hughes and the End of Race Politics

In The End of Race Politics, Coleman Hughes argues that focusing on race in politics and society ultimately hinders progress toward racial equality. Hughes is a writer and commentator known for his critiques of race-based policies, arguing that such policies emphasize differences rather than shared humanity. He believes that the best path to true equality lies in minimizing the role of race in social and political life, an approach he sees as a genuine form of colorblindness.

Hughes’s perspective is grounded in the belief that emphasizing race can perpetuate division and resentment. He argues that race-conscious policies, such as affirmative action, create a sense of unfairness and foster racial resentment among those who feel excluded or disadvantaged by these policies. Hughes also suggests that focusing on race reinforces a victimhood mindset, particularly among minority groups, which he believes can limit their potential by encouraging them to see themselves as disadvantaged based on race alone.

According to Hughes, colorblindness offers a way to transcend racial divisions by treating individuals as individuals, rather than as members of specific racial groups. He advocates for policies that do not consider race and believes that society should move toward race-neutral approaches in areas such as education, employment, and criminal justice. For Hughes, true equality means achieving a society where race no longer matters or dictates opportunities, and he believes that colorblindness is essential for reaching that goal.

Balancing Race-Conscious and Colorblind Approaches: Bonilla-Silva and Hughes in Perspective

The contrasting views of Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and Coleman Hughes highlight a fundamental tension in how to approach race and equality. Bonilla-Silva argues that acknowledging race is necessary to address systemic inequalities, while Hughes believes that focusing on race only deepens divisions. For Bonilla-Silva, ignoring race through colorblindness allows the underlying structures of racism to remain unchallenged and makes it harder to address issues that disproportionately affect marginalized groups. He sees colorblindness as a way of maintaining racial inequality by masking the historical and institutional forces that shape today’s social and economic disparities.

Hughes, however, views colorblindness as a pathway to genuine equality, arguing that emphasizing race reinforces racial differences and fuels division. From his perspective, policies that prioritize race, like affirmative action, risk perpetuating feelings of unfairness and dependency, while also diminishing personal responsibility. Hughes suggests that true equality can only be achieved by transcending racial categories, treating individuals as individuals, and working toward a society where race is irrelevant in matters of policy and identity.

This debate underscores two competing approaches to achieving equality. On one hand, Bonilla-Silva argues that failing to address race directly makes it harder to combat entrenched inequalities. On the other, Hughes contends that racial equality will only be realized by moving beyond race and embracing colorblindness, fostering unity, and de-emphasizing racial distinctions. While both theorists seek to create a more just society, they differ fundamentally in how they believe that goal should be pursued.

Conclusion

The study of race and ethnicity reveals the complexity and power of social categories that, while socially constructed, have very real effects on individuals and institutions. The Rachel Dolezal case demonstrates how tensions between self-identity and social identity can highlight society’s rigid and powerful racial boundaries, showcasing how race is perceived and enforced by societal norms. Sociologists like W.E.B. Du Bois, Michael Omi, Howard Winant, Étienne Balibar, and Stuart Hall have all contributed to our understanding of race as a socially constructed category that impacts lives, institutions, and hierarchies, moving us away from outdated biological perspectives. Their work, along with modern perspectives on individual and structural racism, underscores how race operates within social hierarchies and is embedded in societal systems that perpetuate inequality.

As this article has shown, race and ethnicity are not simply personal identities but are intertwined with broader social forces, influencing everything from economic opportunities and legal outcomes to cultural narratives. By examining both individual and structural racism, scholars and activists work to address racial inequities and challenge societal structures that reinforce discrimination. Moving forward, the debate between approaches like colorblindness and race-conscious policies continues to provoke critical questions about how best to achieve equality, reminding us that understanding race is essential for advancing a more just and inclusive society.

Key Concepts

Colorblind Racism: Colorblind racism is a modern form of racism that ignores race as a factor, asserting that “we are all the same” without addressing racial inequalities. By denying or minimizing race, it obscures the realities of systemic discrimination.

- Example: Policies that avoid tracking racial data in hiring to create “race-neutral” workplaces can unintentionally uphold racial disparities because they ignore existing biases and historical discrimination.

Discrimination: Discrimination is the unfair treatment of individuals based on characteristics like race, gender, or ethnicity, often resulting in reduced opportunities or resources for certain groups.

- Example: A qualified job applicant with a traditionally Black name receives fewer callbacks than an equally qualified applicant with a traditionally white name, reflecting racial discrimination.

Double Consciousness: Introduced by W.E.B. Du Bois, double consciousness describes the experience of marginalized groups in a society that devalues them, as they view themselves both through their own perspective and through society’s biased lens.

- Example: A Black professional in a predominantly white workplace may feel pride in their accomplishments but also feel self-conscious due to stereotypes, navigating their personal identity while confronting societal expectations.

Environmental Racism: Environmental racism refers to the disproportionate exposure of communities of color to environmental hazards and poor environmental conditions due to historical and policy-driven inequalities.

- Example: Residents in Flint, Michigan, a predominantly Black community, faced lead contamination in their water supply, highlighting how environmental risks disproportionately affect marginalized communities.

Ethnicity: Ethnicity is a social category based on shared cultural practices, heritage, language, and traditions, rather than physical traits.

- Example: Someone who identifies as ethnically Irish might participate in Irish cultural traditions, regardless of their racial appearance.

Human Genome Project: The Human Genome Project, completed in 2003, was an international research effort that mapped the human genome, revealing that humans share 99.9% of their genetic material across races, debunking the biological basis of racial categories.

- Example: This project demonstrated that the genetic differences between racial groups are minuscule, reinforcing the view of race as a social construct rather than a biological reality.

Individual Racism: Individual racism involves a person’s prejudiced beliefs or discriminatory actions toward others based on race, reflecting conscious or unconscious biases.

- Example: A store clerk following a Black customer more closely than white customers due to a stereotype that associates Black people with theft.

Intent and Impact: Intent and impact refer to the difference between a person’s intended meaning or purpose (intent) and the actual effect their actions or words have on others (impact).

- Example: A person may unintentionally make a comment that offends someone of a different race; while the intent was not to harm, the impact reinforces racial stereotypes or causes discomfort.

Lost Cause Myth: The Lost Cause myth is a narrative promoted by Southern historians and writers to romanticize the Confederacy, framing the Civil War as a fight over states’ rights rather than slavery and casting Reconstruction as a period of chaos caused by Black incompetence.

- Example: Statues and monuments celebrating Confederate leaders were part of the Lost Cause narrative, aiming to portray the Confederacy as noble and downplay the role of slavery in the Civil War.

Microaggressions: Microaggressions are subtle, often unintentional, comments or actions that convey racial bias, often reinforcing stereotypes or making individuals feel marginalized.

- Example: Telling an Asian American, “Your English is so good!” implies that they are foreign, even if they are fluent English speakers or born in the United States.

Prejudice: Prejudice is a preconceived negative attitude or opinion about a person or group based on characteristics like race, gender, or religion, often without factual basis.

- Example: Assuming that a person is less competent solely because they belong to a specific racial group reflects racial prejudice.

Psychological Wage: Coined by W.E.B. Du Bois, the psychological wage refers to non-material privileges given to poor whites during the Reconstruction era to promote a sense of superiority over Black people, despite shared economic hardships.

- Example: During slavery, poor whites were socially ranked above enslaved Black people, receiving symbolic privileges that reinforced racial divisions rather than uniting them against economic exploitation.

Race: Race is a social construct based on perceived physical characteristics like skin color, used by societies to categorize people and create social hierarchies.

- Example: In the U.S., people are often categorized as “Black,” “White,” “Asian,” or “Latino,” but these categories are not biologically determined and vary across cultures.

Racial Formation Theory: Developed by Michael Omi and Howard Winant, racial formation theory explains how race is socially constructed through historical events, political movements, and economic forces rather than biological differences.

- Example: The shift from Jim Crow laws to the Civil Rights Movement demonstrates how racial categories and meanings evolve in response to changing social and political contexts.

Racism: Racism is a system of beliefs, practices, and institutional structures that maintain inequality by treating certain racial groups as inferior to others.

- Example: Racial disparities in education funding and criminal sentencing are examples of racism embedded in institutions that systematically disadvantage marginalized groups.

Redlining: Redlining was a discriminatory policy that labeled neighborhoods with large Black or immigrant populations as “high risk” for investment, denying residents access to loans and homeownership opportunities.

- Example: Neighborhoods marked in red on government maps were systematically excluded from loans, leading to long-term poverty and lower property values in these communities.

Scapegoating: Scapegoating is the practice of blaming a person or group for problems they did not cause, often to divert attention from the actual sources of issues.

- Example: During times of economic hardship, minority groups are sometimes blamed for “taking jobs,” deflecting from systemic factors that contribute to unemployment.

Sons of Ham Myth: The Sons of Ham myth is a Biblical interpretation that claims Black people are descendants of Ham, one of Noah’s sons, who was cursed, using this myth to justify slavery and racial oppression.

- Example: This myth was historically invoked to defend the enslavement of Africans by arguing that their subjugation was divinely sanctioned.

Stereotype: A stereotype is a widely held but oversimplified belief about a group that reduces individuals to specific traits, often negative.

- Example: Assuming all Asian Americans are academically successful is a stereotype that ignores individual differences and places unfair expectations on individuals.

Structural Racism: Structural racism refers to the systemic policies, practices, and institutional structures that create and sustain racial inequalities across generations.

- Example: The criminal justice system’s disproportionately high incarceration rates for Black men, despite similar rates of drug use across racial groups, reflect structural racism.

Xenophobia: Xenophobia is a fear or distrust of people from other countries or cultures, often resulting in exclusionary or hostile attitudes toward immigrants.

- Example: Policies that restrict immigrant access to public services based on unfounded fears of “overburdening the system” reflect xenophobic attitudes.

Reflection Questions

- How did pseudoscientific claims and religious narratives, such as the Sons of Ham myth, serve to legitimize systems of racial oppression, and what made these explanations so persuasive in their historical context?

- In what ways do Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and Coleman Hughes offer contrasting approaches to achieving racial equality, and what are the potential strengths and limitations of each perspective?

- How does Rachel Dolezal’s case illustrate the tension between self-defined identity and socially assigned racial categories, and what broader implications does this have for discussions about race and authenticity?

- What does W.E.B. Du Bois’s concept of “double consciousness” reveal about the lived experiences of African Americans, and how does this idea continue to resonate in contemporary social life?