Table of Contents

- Learning Objectives

- Introduction

- Medical Sociology and the Social Construction of Health and Healthcare

- Theorizing Health and Healthcare

- Inequities in Health and Healthcare in the US

- The Social Organization of the Healthcare Industry

- Conclusion

- Key Concepts

- Reflection Questions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, students will be able to:

- Define medical sociology and explain how social factors shape health, illness, and healthcare practices.

- Explain the social construction of illness, including how diagnoses, symptoms, and medical legitimacy are shaped by cultural beliefs, institutional practices, and social power.

- Describe the illness experience as a socially embedded process influenced by stigma, visibility of symptoms, and interpersonal recognition.

- Analyze how medical knowledge is socially constructed, using historical and contemporary examples of gender and racial bias in diagnosis and treatment.

- Apply Talcott Parsons’ concept of the sick role, including its rights, responsibilities, and limitations in chronic and contested conditions.

- Interpret Michel Foucault’s theory of the medical gaze, including its implications for surveillance, normalization, and the expansion of medical authority.

- Evaluate the concept of medicalization, including its causes, critiques, and impacts on how behaviors and identities are treated as medical problems.

- Assess how health inequities manifest across race, class, and gender, integrating empirical evidence and sociological theory to explain disparities in access, treatment, and outcomes.

- Compare healthcare systems in the U.S., Canada, the UK, Norway, Cuba, Singapore, and Germany, analyzing how they reflect differing societal values, priorities, and trade-offs.

- Critically reflect on healthcare as a socially constructed system, and examine how health systems reinforce or challenge broader patterns of inequality.

Introduction

In recent decades, diagnoses of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) have surged across the United States, pointing to a shift not merely in children’s behavior but in how society perceives health and illness. By 2016, nearly 10% of children aged 4–17 had been diagnosed with ADHD, compared to about 6% in 2000 (Source). This rise reflects evolving diagnostic practices and heightened societal pressures rather than any biological change within the population. Expanded diagnostic criteria now capture more children with milder symptoms, while academic demands and increased awareness of behavioral health have further contributed to ADHD’s prevalence. Boys are diagnosed at over twice the rate of girls—13% compared to 5.6%—due to more overt hyperactivity that aligns closely with traditional criteria, while children from lower-income households experience higher diagnosis rates, reflecting disparities in access to behavioral support and school resources (Source).

This increase raises crucial questions about how society defines and responds to health and illness. Health, sociologists argue, is not solely a biological condition but also a socially constructed concept, shaped by cultural beliefs, societal norms, and institutional practices. Through the lens of medical sociology, we can examine how phenomena like the rise in ADHD diagnoses illuminate broader social forces, from shifting educational expectations to new standards of behavior.

This chapter explores these dynamics in-depth, investigating core concepts in the sociology of health, such as the social construction of illness, health inequities, and the structure of healthcare systems. By examining health inequities across race, class, and gender and assessing how healthcare systems themselves are socially constructed, we can better understand the complex interplay between social forces and health. Together, these insights reveal how both health outcomes and access to care are shaped by larger social patterns, encouraging a critical approach to health and healthcare in modern society.

Medical Sociology and the Social Construction of Health and Healthcare

Medical sociology is a subfield of sociology that investigates how social factors, from culture to power structures, shape health, illness, and healthcare practices. While traditional medicine often views health as purely biological, medical sociology reveals that health is also deeply influenced by societal beliefs, values, and inequalities. By examining health as a social construct, this field of sociology explores three key dimensions: how society defines illness, the subjective experience of living with illness, and the medical knowledge that guides practices and treatments.

Social Construction of Illness

The social construction of illness refers to the ways societies define, categorize, and respond to health conditions, highlighting that illness is not solely a biological phenomenon but is also shaped by cultural beliefs, social norms, and historical changes. This framework shows that labeling certain conditions as “illnesses” influences how the sick are treated, both medically and socially, determining who is granted access to care, support, and empathy. For example, conditions like chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) were initially met with skepticism because their symptoms did not fit traditional diagnostic categories. However, shifts in medical understanding and advocacy have since legitimized these conditions, impacting both treatment options and societal attitudes toward affected individuals.

This evolving view of illness reflects broader social and medical influences that shape who is deemed “sick” and what treatments they receive. As such, the social construction of illness highlights that definitions of illness are not static but respond to changes in medical knowledge, societal priorities, and cultural beliefs, which determine how individuals experience and are supported through their health challenges.

Social Construction of Illness Experience

Beyond simply labeling an illness, the social construction of the illness experience considers how individuals live with and interpret their conditions within a social context. This approach reveals that illness is not only a medical condition but also a deeply subjective and social experience. For example, individuals with chronic pain disorders, like fibromyalgia, often face skepticism from others because their symptoms are not visibly apparent. This “invisible” nature of their illness can lead to social isolation and frustration, as the legitimacy of their pain may be questioned. Dr. Elaine Scarry, in her 1985 book, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World, discusses how these challenges affect the illness experience, where patients’ realities are shaped as much by others’ perceptions as by their physical symptoms. Recognizing the social aspects of illness experience allows medical professionals to offer more empathetic, individualized care that considers the social dynamics influencing patients’ well-being.

Social Construction of Medical Knowledge

The social construction of medical knowledge reveals that what is considered ‘true’ in medicine is not always objective but is instead shaped by cultural beliefs, institutional biases, and historical contexts. Throughout history, societal biases have influenced medical perspectives and treatments. For instance, in the 19th and early 20th century, women’s health concerns were often dismissed as ‘female hysteria’ or other gendered diagnoses, reflecting cultural beliefs about gender roles rather than objective medical criteria. These biases had significant impacts, resulting in inadequate care and misunderstanding of women’s health issues.

Even today, gender biases persist. Research, such as the 2001 study by Diane E. Hoffman and Anita J. Tarzian titled “The Girl Who Cried Pain: A Bias Against Women in the Treatment of Pain,” highlights how women are less likely than men to receive timely pain management in emergency settings. Additionally, medical research has historically prioritized male subjects, leading to gaps in understanding how diseases and medications impact women. Recognizing that medical knowledge is socially constructed encourages a more critical approach to healthcare—one that questions assumptions of objectivity and calls for diversity in research, transparency in clinical trials, and efforts to reduce implicit biases in healthcare.

***

The social construction of health and healthcare shows that illness is not merely biological but a complex phenomenon shaped by cultural beliefs, historical contexts, and social structures. By examining the social construction of illness, the lived experience of illness, and the development of medical knowledge, medical sociology reveals how societal values profoundly shape healthcare practices and individual experiences. This critical perspective enables healthcare providers, policymakers, and communities to address health holistically, considering the social factors that define, affect, and regulate illness. As we turn to broader sociological theories—Parsons’ sick role, Foucault’s medical gaze, and the concept of medicalization—we delve into the ways healthcare systems uphold social norms, reinforce authority, and expand medical influence over personal and societal dimensions of health.

Theorizing Health and Healthcare

Understanding health and healthcare through a sociological lens involves examining how society defines, manages, and institutionalizes illness. Three influential theories—Talcott Parsons’ concept of the “sick role,” Michel Foucault’s “medical gaze,” and Irving Zola and Peter Conrad’s notion of “medicalization”—illuminate different dimensions of this relationship. Parsons’ functionalist approach highlights the social roles and responsibilities assigned to those who are ill, helping maintain social order. Foucault’s work reveals how medical authority extends beyond treatment, shaping norms and expectations for health and behavior. Conrad and Zola’s concept of medicalization expands this view, showing how social and behavioral aspects of life increasingly fall under medical jurisdiction. Together, these theories suggest that health and healthcare are deeply embedded in social norms, authority structures, and cultural definitions of normalcy and deviance.

Functionalism: Talcott Parsons and the Sick Role

The functionalist perspective, represented by Talcott Parsons (1902-1979), emphasizes how various parts of society work together to maintain stability. In his book The Social System (1951), Parsons introduced the concept of the “sick role” to describe how illness is managed within society. Illness disrupts an individual’s ability to fulfill their roles and responsibilities, which, if unaddressed, could lead to social instability. To mitigate this disruption, Parsons argued, society grants individuals who are genuinely ill certain rights, but it also imposes responsibilities to ensure the return to health and stability. This dynamic helps society regulate illness, promoting order and consistency across families, workplaces, and communities.

The sick role includes two primary rights: the exemption from usual roles and responsibilities (such as work or caregiving) and freedom from blame for one’s condition. However, these rights come with expectations. The sick person must recognize that their condition is undesirable and strive to recover, and they are expected to seek legitimate medical help, aligning with society’s broader needs for productivity and stability. Parsons’ model underscores the authority of the medical profession, as doctors determine whether an individual’s illness is legitimate.

In applying this model, Parsons also addressed “non-legitimate sickness,” where individuals claim illness without formal medical diagnosis or remain sick without evidence. Sociologist Eliot Freidson expanded on Parsons’ model by introducing categories of sickness: conditional (temporary), unconditional (long-term or terminal), and illegitimate (disputed or stigmatized conditions). The sick role has faced critique for its limited applicability, particularly with chronic illnesses, where patients may not fully recover or may lack the means to fulfill their obligations to seek professional help. Sociologists like Anthony Giddens argue that the sick role oversimplifies illness experiences and overlooks the role of social disparities in accessing healthcare.

In sum, the sick role offers a structured way to understand the societal expectations of illness, establishing norms and guiding how society manages the disruption of illness. This theory provides a foundation for examining the social function of healthcare but remains limited in capturing complex or chronic conditions.

Conflict Theory: Michel Foucault and the Medical Gaze

Where Parsons’ sick role offers a social framework for managing illness, Michel Foucault’s (1926-1984) “medical gaze” provides a perspective on the authority embedded in medicine itself. In The Birth of the Clinic (1963), Foucault described the medical gaze as a detached, clinical approach to patients, in which physicians focus on biological data and objective measures rather than how the patient described their experiences. The medical gaze represents a shift from older forms of medical practice, which depended heavily on patients’ narratives, to a form of medicine centered around scientific observation and categorization.

Foucault argued that this clinical approach does more than diagnose and treat patients; it also establishes control. By examining patients through the medical gaze, healthcare professionals set standards for what is “normal” or “abnormal” in health, influencing treatment and shaping how people perceive and regulate their bodies. One example is the use of Body Mass Index (BMI) as a standard for measuring a “healthy” weight. BMI defines categories like “underweight,” “normal weight,” and “obese,” which often become labels for how people see themselves. Individuals labeled “obese” by BMI standards may feel pressured to seek medical treatments or alter their lifestyles to align with these health norms, even if they feel physically well. The medical gaze, through tools like BMI, thus contributes to a broader form of social control, where people adjust their behaviors and appearances to meet medical definitions of health.

Foucault’s medical gaze further explains the expansion of medical authority into everyday life, laying the foundation for the concept of “medicalization.” By categorizing and diagnosing behaviors, physical attributes, and lifestyle choices, the medical gaze allows medicine to extend its influence beyond disease treatment, subtly guiding personal and social expectations. In this way, Foucault’s theory highlights how medical authority can shape societal values and reinforce norms, creating a culture where medical professionals hold significant influence over how individuals view health and illness.

Medicalization and Expanding the Boundaries of Medicine

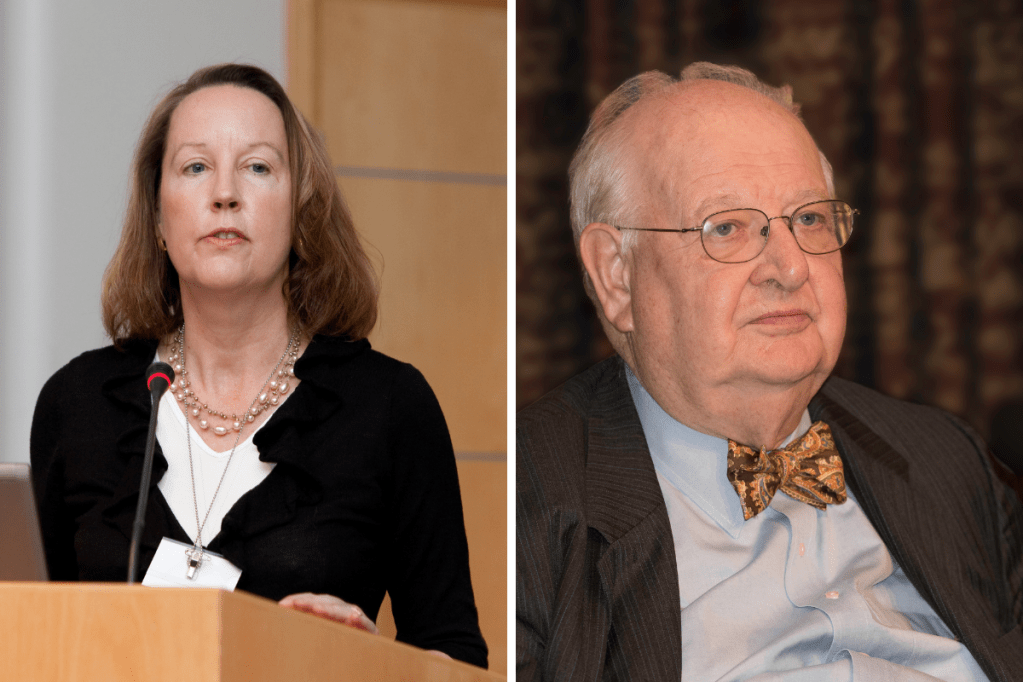

Building on Foucault’s insights into medical authority, sociologists Irving Zola (1935-1994) and Peter Conrad (1945-2024) developed the concept of medicalization to explore how various aspects of daily life are increasingly defined as medical problems. Zola’s 1972 article, “Medicine as an Institution of Social Control,” argued that medicine has become a powerful social institution, extending its reach to manage non-medical areas of life, such as aging, addiction, and social behaviors. Peter Conrad further expanded on this idea in his book The Medicalization of Society (2007), examining how conditions like ADHD, menopause, and erectile dysfunction have become medicalized.

Medicalization occurs through various processes. It often involves the expansion of what is considered a medical issue, as behaviors once seen as normal—like shyness or sadness—are redefined as social anxiety or depression. Medical intervention also shifts solutions from personal or social realms to medical treatments, such as pharmaceuticals or surgery. Pharmaceutical companies play a major role in driving medicalization, often marketing medications as solutions to newly defined conditions, which creates economic incentives for redefining health and illness.

Critics of medicalization, such as sociologist Nickolas Rose, argue that Conrad and Zola’s focus on institutional power portrays individuals as passive. Rose suggests that individuals engage with medical knowledge, actively using it to shape their identities, rather than being mere subjects of medical authority. Allan Horwitz and Jerome Wakefield’s The Loss of Sadness (2007) contends that medicalization can provide validation and access to resources, arguing for distinctions between helpful medicalization and over-pathologizing. In environmental health, Phil Brown’s work emphasizes that patient advocacy often drives recognition of conditions, countering the view that medicalization is strictly a top-down process.

Overall, medicalization offers a framework for understanding how medicine shapes not only health but also societal norms. It reveals the influence of economic and social forces in expanding medical authority and highlights the balance needed between helpful medicalization and the risks of pathologizing normal human experiences.

Synthesizing Theories: A Sociological Perspective on Health and Healthcare

These three theories—Parsons’ sick role, Foucault’s medical gaze, and the concept of medicalization—together offer a multi-faceted view of health and healthcare as socially regulated, culturally influenced, and economically driven. The sick role explains how society manages illness through structured expectations, the medical gaze reveals how medical authority standardizes norms, and medicalization shows how this authority can extend into personal and social domains. Each theory highlights different dimensions of healthcare’s role in shaping social order, individual behavior, and societal values.

This integrated view challenges us to see health as both a personal and social construct, shaped not only by biological needs but also by social forces that reinforce certain norms and inequalities. By critically examining healthcare practices through these perspectives, we can better understand how the structure of healthcare systems may perpetuate disparities across race, class, and gender. As we turn to health inequities in the U.S., these theories offer essential tools for analyzing how access, quality of care, and health outcomes reflect broader social patterns of inequality.

Inequities in Health and Healthcare in the US

Healthcare inequities are widespread across race, class, and gender, underscoring how social structures influence health outcomes. The theories of Parsons, Foucault, and the concept of medicalization demonstrate that healthcare systems are not neutral entities; they shape, and are shaped by, societal values and inequalities. By applying these sociological insights, we can better understand why some groups consistently experience poorer health outcomes, limited access to resources, or greater burdens of illness.

Examining these disparities is essential, not only for addressing issues of justice but also for improving public health. By identifying where inequities occur and understanding the social contexts that contribute to them, policymakers, healthcare providers, and communities can develop targeted strategies that promote fairer and more equitable access to care. Focusing on how race, gender, and class shape health outcomes reveals the broader societal forces that perpetuate health disparities and provides pathways for meaningful reform.

Race and Health Inequities

Race is one of the most significant predictors of health disparities, as epidemiological data consistently shows stark contrasts in health outcomes between racial groups. For example, Black Americans are nearly twice as likely as white Americans to die from heart disease and stroke (Source) and are 1.5 times more likely to have diabetes (Source). These health inequities stem from a complex web of structural, socioeconomic, and historical factors that disproportionately affect communities of color.

A major contributing factor to these disparities is unequal access to quality healthcare. Many Black and Hispanic neighborhoods have fewer healthcare facilities and higher concentrations of lower-quality providers compared to predominantly white areas (Source). This lack of access can delay diagnoses and treatment for preventable conditions, leading to higher rates of morbidity and mortality in these communities. Additionally, racial minorities are more likely to be uninsured or underinsured, increasing their reliance on emergency care rather than preventive healthcare, which in turn contributes to poorer long-term health outcomes (Source).

Environmental factors also play a significant role. Historically, redlining and discriminatory housing policies forced many Black families into neighborhoods with limited resources, higher levels of pollution, and lower investment in community health infrastructure. As a result, exposure to environmental hazards—such as air pollution and lead in housing—is higher in communities of color, contributing to higher rates of respiratory illnesses, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic conditions (Source).

Systemic biases within the healthcare system further exacerbate racial health disparities. Research has shown that Black patients often receive different standards of care due to implicit biases among healthcare providers, who may underestimate the severity of their symptoms or assume they have a higher pain tolerance (Source). For example, studies indicate that Black patients are less likely to receive pain management for the same conditions as their white counterparts (Source). These unconscious biases impact the quality of care received by racial minorities, compounding health disparities.

The historical exploitation of Black and Indigenous communities in medical research has further deepened this mistrust. Harriet Washington’s 2006 book, Medical Apartheid documents the extensive history of unethical experimentation on Black Americans, from the well-known Tuskegee Syphilis Study to lesser-known practices such as forced sterilizations and medical testing without consent. This history has left a legacy of distrust toward medical institutions, as many Black Americans feel wary of a system that has historically treated their communities as subjects rather than patients. This mistrust can discourage individuals from seeking medical care, further widening health disparities in underserved populations.

These interconnected factors reveal that racial health disparities are not simply a matter of individual lifestyle or genetics but are rooted in long-standing social, economic, and institutional inequities. As a result, health outcomes for racial minorities remain shaped not only by biological factors but by a legacy of social and structural inequality that continues to influence healthcare access, quality, and trust in medical institutions

Class and Health Inequities

Socioeconomic status, or class, is another of the strongest predictors of health outcomes, significantly affecting access to healthcare, health behaviors, and overall life expectancy. People in lower-income brackets are less likely to have health insurance, which limits their access to preventive care and increases their reliance on emergency services for health needs (Source). According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, uninsured Americans are more likely to delay or forgo treatment, leading to worsened health outcomes as preventable or manageable conditions go untreated (Source). Economic disparities also give rise to the “social gradient in health,” where each step down in income correlates with poorer health outcomes and increased mortality rates.

In their 2020 book on “deaths of despair,” entitled Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton highlight how these class-based health inequities have driven a crisis among lower-income, predominantly white communities in the U.S. The term “deaths of despair” refers to rising mortality rates caused by suicide, drug overdose, and alcohol-related liver disease, particularly among working-class Americans without a college education. Between 1999 and 2017, mortality rates for white Americans aged 45-54 with only a high school education rose by 45%, largely due to these causes (Source). These “deaths of despair” are largely concentrated in economically stagnant regions where social support structures have weakened, stable jobs have disappeared, and opportunities for upward mobility have dwindled, creating a unique health crisis that has even contributed to declining life expectancy among this demographic—a trend rarely seen in other wealthy nations.

Case and Deaton argue that these deaths are rooted not simply in individual choices but in structural economic factors. They suggest that as job opportunities diminish, particularly in areas that once relied on manufacturing and other blue-collar industries, individuals face increased stress, social isolation, and financial instability. The resulting loss of identity and purpose among affected populations fosters a sense of hopelessness, leading many to self-medicate with alcohol or opioids or, in more severe cases, resort to suicide.

Economic instability also impacts access to healthcare and mental health resources, as many low-income Americans lack comprehensive health coverage or live in “healthcare deserts” where medical facilities are sparse. Without affordable, accessible care, preventive health needs go unmet, increasing the likelihood of chronic conditions like diabetes, hypertension, and depression. This lack of access compounds the cycle of poverty and poor health, as untreated conditions can affect individuals’ ability to work, further exacerbating financial strain.

The concept of ‘deaths of despair’ underscores that class-based health disparities are deeply intertwined with economic instability and the erosion of social support systems. Health outcomes for lower-income populations remain closely linked to these broader economic and social conditions, illustrating how financial hardship and limited access to healthcare perpetuate a cycle of poor health and reduced life expectancy in economically disadvantaged communities.

Gender and Health Inequities

Gender is another social category that significantly shapes health outcomes, influencing not only physical health through biological sex differences but also through a complex network of social expectations, economic roles, and cultural norms. These factors impact how individuals access healthcare, the health behaviors they adopt, and their overall well-being. As with other social determinants, gendered health disparities reveal that health outcomes are shaped not just by individual choices but by broader social structures that influence opportunities, risks, and support systems.

For women, health inequities are shaped by both social roles and economic responsibilities, although women generally have a higher life expectancy and often fare better in certain health outcomes compared to men. However, women’s health concerns are frequently misunderstood or underprioritized by the healthcare system, particularly in areas like chronic pain and reproductive health (Source). This lack of prioritization can lead to misdiagnosis, delayed treatment, and overall lower quality of care. Furthermore, women often face unique economic challenges in accessing healthcare, including gaps in insurance coverage due to part-time or low-wage work that may lack benefits (Source). These healthcare challenges illustrate how gendered roles and systemic bias affect women’s health outcomes.

Men, on the other hand, experience health inequities shaped by societal norms surrounding masculinity, which often discourage help-seeking behaviors and preventive care. Cultural expectations around masculinity, or what is called “The Stoic Mask,” can deter men from seeking regular medical check-ups or mental health support, actions that may be perceived as signs of weakness. This reluctance to seek help has significant implications, as men account for nearly 80% of suicides in the United States, with suicide rates approximately 3.5 times higher than for women (Source). Men are also less likely to seek treatment for mental health conditions, with only about one-third of those experiencing depression or anxiety receiving adequate care (Source). As a result, conditions like depression, substance abuse, and preventable chronic illnesses often go unaddressed until they reach critical stages, contributing to these high rates of untreated mental health issues among men.

In addition, men are more likely to work in physically dangerous jobs, such as construction, manufacturing, and mining, where the risks of injury, exposure to hazardous substances, and occupational illnesses are significantly higher (Source). For instance, in 2021, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that construction had one of the highest workplace fatality rates, with about 9.5 deaths per 100,000 workers, while logging and fishing—industries predominantly occupied by men—had rates as high as 132 and 130 deaths per 100,000 workers, respectively (Source). These roles not only increase physical health risks but also impact mental health, as these high-risk jobs often lack sufficient mental health support and leave workers with physical injuries that may result in chronic pain or disability.

Together, these insights underscore how social expectations and structural roles influence health outcomes for both men and women beyond biological differences. By examining gendered health disparities, it becomes clear that health is shaped by social factors, where opportunities, risks, and support systems significantly impact well-being.

These racial, class-based, and gendered disparities in health outcomes reveal underlying structural inequities that shape who benefits most from healthcare and who remains vulnerable. To understand how these disparities persist, it’s crucial to examine the organization of healthcare itself as a socially constructed system, with each country’s model reflecting specific values and choices.

The Social Organization of the Healthcare Industry

Healthcare systems are often perceived as natural, uniform structures within society, yet they are, in reality, socially constructed and reflect the specific values, priorities, and policy choices of each society. Decisions about access, funding, and government involvement shape not only how healthcare is delivered but also who benefits most from it. In the United States, healthcare operates largely as a market commodity, while countries such as Canada, Britain, Norway, and Cuba structure their systems to prioritize universal access, viewing healthcare as a public good. Other nations, like Singapore and Germany, blend individual responsibility with government oversight to varying degrees. Examining how these countries organize their healthcare systems reveals that no single model is inevitable; rather, healthcare systems are the product of unique societal choices, each with strengths, limitations, and implications for social equity.

The United States Healthcare System: A Market-Driven Model

The United States has chosen to structure its healthcare system primarily as a market-driven industry, where healthcare services are treated as commodities to be bought and sold. Access to healthcare in the U.S. is largely mediated by private insurance companies, often tied to employment (Source). For those without employer-provided insurance, options are limited, often resulting in high out-of-pocket costs or reliance on government programs like Medicaid and Medicare. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), or “Obamacare,” introduced in 2010, aimed to address some of these gaps by providing subsidies for private insurance, expanding Medicaid eligibility in participating states, and establishing health insurance marketplaces. Additionally, the ACA introduced consumer protections, such as prohibiting denial of coverage for pre-existing conditions and requiring that preventive services be covered at no additional cost.

The U.S. system has some strengths, particularly in offering a high degree of choice in providers and treatments, and it is known for rapid innovation, driven by competition in the private sector. However, these advantages come with significant weaknesses, most notably high costs and inequitable access (Source). Despite spending more on healthcare than any other nation—approximately 18% of GDP—health outcomes in the U.S. are often poorer than in other developed countries, with a life expectancy of 77 years and an infant mortality rate higher than that of most European countries (Source). This model emphasizes individual responsibility and capacity to pay, which creates substantial disparities in healthcare access and outcomes.

Socialized and Universal Models: Canada, Britain, Norway, and Cuba

In contrast, many countries have chosen healthcare models that prioritize universal access over market-based provision. Canada operates a single-payer healthcare system where the government finances healthcare through taxes, making it accessible to all citizens. This model minimizes out-of-pocket costs for essential services and emphasizes healthcare as a public good (Source). Canada’s single-payer system is often praised for its equitable access and cost efficiency, as administrative costs are lower in a streamlined, publicly funded system. However, challenges arise in the form of long wait times for certain procedures, partly due to limited resources and government budgets that must balance other public needs, reflecting Canada’s choice to prioritize access over immediacy (Source).

The United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS) similarly exemplifies a government-funded healthcare model. Established after World War II, the NHS provides universal healthcare funded through taxes, with most services delivered directly by government-employed staff. The NHS ensures nearly universal access without direct charges to patients, and its centralized structure allows for efficient resource distribution. However, the NHS also faces pressures in managing demand and often experiences resource shortages, particularly as population needs grow and funding becomes strained. These challenges have sparked debates about whether some limited private involvement could enhance service availability without compromising the NHS’s public focus (Source).

Norway’s system combines universal coverage with some private options, funded by a mix of taxes and social insurance, allowing flexibility while ensuring core medical needs are universally met. Norway’s model is known for high-quality care and excellent health outcomes, with life expectancy at 82 years and low infant mortality. However, because it incorporates private elements alongside public funding, some critics argue that wealthier individuals may be able to access services more quickly through private channels, creating potential inequalities even within a socially equitable framework (Source).

Cuba’s healthcare system is one of the most highly socialized globally, with the government directly funding, organizing, and delivering all medical services. Despite limited resources, Cuba has achieved impressive health outcomes, largely due to its focus on preventive care and community-based medicine. This model demonstrates the strengths and limitations of a fully socialized approach, achieving health outcomes comparable to those of wealthier nations at a fraction of the cost (Source). However, resource scarcity and limited access to advanced medical technologies can impact the quality of care in certain areas.

Limited Social Safety Nets: Singapore and Germany

While some countries have embraced highly socialized healthcare systems, others emphasize individual responsibility with limited social support. Singapore’s healthcare system combines mandatory savings, individual responsibility, and targeted government assistance through Medisave, where citizens contribute a portion of their income to personal healthcare accounts. This model is known for its cost efficiency, with healthcare spending at only about 4% of GDP, as it encourages citizens to take financial responsibility for healthcare costs. However, this approach can place a substantial burden on low-income individuals and families, as the government’s role is limited, and healthcare access relies heavily on individual financial capacity.

Germany’s healthcare system operates a unique system that blends public and private elements within a framework of social solidarity. Funded through nonprofit “sickness funds,” Germany’s multi-payer system provides healthcare for nearly all citizens while allowing for competition among insurers. This system achieves universal coverage with a high degree of individual choice. However, its multi-payer structure introduces administrative complexity, and some critics argue that administrative costs are higher than those of single-payer systems, with increased expenses that could impact overall efficiency.

***

The global variety in healthcare systems illustrates that access to healthcare is not determined by a single, predetermined model but is instead shaped by each society’s social values and policy decisions. Countries like Canada, Britain, Norway, and Cuba prioritize universal access, conceptualizing healthcare as a public good accessible to all. Meanwhile, nations such as the United States, Singapore, and Germany emphasize market principles or personal responsibility to different extents, reflecting diverse societal views on healthcare as either a right or a commodity. Understanding healthcare as a socially constructed system enables societies to critically examine and refine their priorities, acknowledging that each model’s structure has distinct implications for equity, access, and health outcomes.

Conclusion

This exploration of health and healthcare through a sociological lens reveals that health outcomes are not purely biological but are shaped by social structures and the values embedded within them. Concepts like the social construction of illness, the medical gaze, and medicalization illustrate how health, illness, and even the very knowledge guiding medical practices are influenced by cultural beliefs and institutional priorities. Talcott Parsons’ “sick role” emphasizes society’s expectations of those who are ill, while Foucault’s medical gaze highlights the power dynamics within medical practices, showing how patients are often seen as objects to be managed rather than individuals with unique experiences. These theories underscore the impact of social norms and institutional practices on individuals’ health experiences and outcomes.

The organization of healthcare systems worldwide further illustrates that the structure of healthcare is a deliberate social choice, reflecting each society’s priorities. While the United States employs a market-driven approach that often leads to health disparities, other countries like Canada, the United Kingdom, Norway, and Cuba have chosen universal or socialized models that frame healthcare as a public good. Singapore and Germany blend elements of personal responsibility and government support, reflecting unique societal compromises. Each system’s structure impacts health equity, access, and quality of care in distinct ways. By examining these choices, we understand how healthcare systems are not inevitable but constructed based on social, economic, and cultural contexts, highlighting the potential for informed change toward more equitable health outcomes.

Key Concepts

Affordable Care Act (ACA): A 2010 healthcare reform law in the United States aimed at expanding health insurance coverage, increasing access to preventive services, and prohibiting denial of coverage for pre-existing conditions.

- Example: The ACA allowed millions of Americans, especially those with pre-existing conditions, to gain health insurance coverage and receive preventive care services at no additional cost, reducing barriers to healthcare.

Deaths of Despair: A term coined by Anne Case and Angus Deaton to describe rising mortality rates from suicide, drug overdose, and alcohol-related disease, often among working-class communities facing economic and social decline.

- Example: Between 1999 and 2017, “deaths of despair” increased significantly among middle-aged white Americans without a college education, attributed to economic instability, loss of social support, and substance abuse.

Female Hysteria: A now-discredited medical diagnosis historically used to explain various physical and mental health symptoms in women, often attributed to a woman’s perceived emotional instability. This diagnosis reflected societal norms and biases about gender rather than biological evidence.

- Example: In the 1800s, women who exhibited anxiety, irritability, or depression might be diagnosed with “hysteria” and treated with rest cures or institutionalization, showing how medical labels reflected gendered social biases.

Healthcare Deserts: Areas with limited or no access to healthcare facilities and providers, making it difficult for residents to receive timely or adequate care. These areas are often found in rural regions or underserved urban neighborhoods.

- Example: In some rural parts of the U.S., residents may live hours from the nearest hospital, limiting access to emergency care and preventive services and contributing to poorer health outcomes.

Medical Gaze: A concept by Michel Foucault describing the clinical, objective approach doctors use to examine patients, focusing on biological data over the patient’s personal narrative. This gaze defines norms for “healthy” and “unhealthy” bodies, often creating pressure to conform.

- Example: A doctor might assess a patient’s BMI to determine if they are “obese” according to medical standards, potentially leading the individual to pursue weight loss treatments even if they feel healthy.

Medical Sociology: The study of how social factors—such as culture, socioeconomic status, and power structures—influence health, illness, and healthcare systems. It examines how health is shaped not only by biological factors but also by societal beliefs, values, and inequalities.

- Example: Medical sociologists study the rise in ADHD diagnoses to understand how educational pressures, diagnostic practices, and societal norms contribute to its prevalence, beyond biological explanations.

Medicalization: The process by which non-medical issues are defined and treated as medical conditions, often resulting in new treatments and interventions, sometimes driven by pharmaceutical companies or social trends.

- Example: Behaviors once seen as shyness are now often diagnosed and treated as social anxiety disorder, reflecting changing medical definitions and a trend toward pharmaceutical interventions.

Sick Role: A concept by Talcott Parsons describing the societal expectations placed on individuals when they are ill. It includes the right to be excused from normal duties and the obligation to seek medical help and try to recover.

- Example: A person with the flu may take sick leave from work (a right) but is expected to follow medical advice, such as rest or medication, to recover and return to their responsibilities.

Social Construction of Illness: A concept that illness is not solely a biological condition but is also shaped by societal norms, cultural beliefs, and historical changes. This influences what is considered an illness, how individuals with it are treated, and what resources are made available.

- Example: Chronic fatigue syndrome was initially doubted as a legitimate illness until changing medical perspectives and advocacy efforts led to its recognition, impacting both public perceptions and treatment options.

Social Construction of Illness Experience: This perspective focuses on how individuals experience and interpret their illness within their social context. Illness is understood as not only a medical condition but also a personal and social experience affected by factors like stigma and support systems.

- Example: Individuals with invisible illnesses like fibromyalgia often face skepticism about their symptoms, leading to isolation and frustration as their pain is doubted by others, impacting their mental health.

Social Construction of Medical Knowledge: The idea that medical knowledge is not entirely objective and is shaped by cultural values, social norms, and institutional biases within society.

- Example: For decades, clinical trials predominantly included male participants, leading to gaps in understanding how drugs affect women differently. As a result, some medications that were deemed safe based on male-only studies were later found to have adverse effects in women, highlighting how medical knowledge reflects societal biases in research practices.

Social Gradient in Health: The concept that health outcomes improve with each step up in socioeconomic status. Lower-income individuals generally experience poorer health, while wealthier individuals have better access to healthcare and health resources.

- Example: In cities, affluent neighborhoods often have higher life expectancies and lower rates of chronic diseases than poorer neighborhoods, partly due to better access to healthcare and healthier living conditions.

The Stoic Mask: A concept describing societal expectations around masculinity that discourage men from expressing vulnerability or seeking help for mental and physical health issues, often leading to untreated health conditions.

- Example: Men may avoid seeking mental health support due to the perception that it’s “weak” to discuss emotions, which contributes to higher rates of untreated depression and suicide among men.

Reflection Questions

- How does Talcott Parsons’ concept of the sick role help us understand the expectations placed on individuals who are ill, and what are the limitations of this framework in addressing chronic illness or invisible disabilities?

- In what ways does Michel Foucault’s idea of the “medical gaze” illustrate the power dynamics embedded in the patient-provider relationship, and how does this affect the way we define and treat illness?

- What does it mean to say that medical knowledge is socially constructed, and how do historical examples, such as shifting views on hysteria or homosexuality, demonstrate the influence of culture, power, and politics on medical science?

- How do structural inequalities related to race, class, and gender contribute to rising “deaths of despair” (e.g., drug overdoses, suicide, alcohol-related illnesses), and what does this reveal about the relationship between social conditions and health outcomes?