Table of Contents

- Learning Objectives

- Introduction

- Socialization: Understanding the Foundations of Society and Self

- Sociological Theories in Action: Examining Social Media’s Role in Shaping Beauty Standards

- Theories of Socialization: Understanding How We Learn to Be Social

- Conclusion

- Key Terms

- Reflection Questions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, students will be able to:

- Define socialization and explain its role in transmitting cultural norms, values, and behaviors across individuals and generations.

- Distinguish between primary, secondary, anticipatory, organizational, and forced socialization, using examples from educational, family, and institutional settings.

- Identify major agents of socialization—including family, education, religion, peers, media, political, and economic institutions—and evaluate their influence on individual identity and behavior.

- Explain the concepts of status and role, including distinctions between ascribed and achieved status, and analyze how individuals navigate multiple, and sometimes conflicting, social roles.

- Differentiate between self-identity and social identity, and evaluate how societal expectations, stereotypes, and social structures shape individual self-concepts.

- Analyze how socialization is shaped by and reinforces categories of difference, including gender, race, and class, using sociological examples and images.

- Apply major sociological theories to the process of socialization, including:

- Cooley’s looking-glass self

- Mead’s stages of role-taking and the generalized other

- Piaget’s stages of cognitive development

- Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development and scaffolding

- Use symbolic interactionism, structural functionalism, and conflict theory to interpret a case study on how social media influences beauty standards and body image.

- Evaluate the dynamic nature of socialization, including the process of resocialization and its role in personal transformation within different life stages or institutions.

- Reflect on how individuals are shaped by and help shape their social environments, recognizing the interplay between agency, structure, and cultural context.

Introduction

How do you know what to wear to a job interview, how to greet a new acquaintance, or even which side of the road to drive on? These behaviors feel automatic, yet they are deeply shaped by socialization. They are the process by which we learn the norms, values, and behaviors expected in society. In the last module, we explored culture and social norms, the frameworks that give structure and meaning to human life. But how do these norms become part of who we are? How do we internalize societal expectations, and what happens when we encounter new roles or settings that require us to adapt?

Socialization is the key to understanding these questions. It is through socialization that we learn not only how to function in society but also how to develop a sense of self and navigate the roles we play in our lives. From the family and school to social media platforms like TikTok, the agents of socialization around us are constantly shaping who we are and how we see the world. By examining the processes, agents, and theories of socialization, we can better understand how individuals are connected to the larger social structures that define our lives.

Socialization: Understanding the Foundations of Society and Self

Picture yourself on the first day of college. The campus is alive with movement and energy. Students are shuffling between classes, exchanging quick greetings, or nervously glancing at their schedules. Some gather in small groups, laughing as if they’ve known each other for years, while others sit alone, earbuds in, taking it all in. Beneath the surface of this vibrant scene, something profound is happening: everyone is navigating a web of unwritten rules about how to act, interact, and belong. How do they know what to do? The answer lies in socialization, the process through which we learn the norms, expectations, beliefs, and values that allow us to function in society.

Socialization is the thread that connects us to our social worlds. It’s how we come to understand what’s considered polite or rude, what’s expected in different settings, and how to interpret the behaviors of others. But it’s not just about learning rules—it’s about learning how to learn them. Think about how, as a new student, you might figure out the norms of college life. At first, you might feel uncertain: Should you raise your hand in a lecture? Is it okay to grab coffee during class? Over time, you observe others, ask questions, and adapt your behavior. This gradual process of absorbing and internalizing societal norms is what makes socialization so essential—and so powerful.

In the previous chapter, we explored the concept of culture and the norms that guide behavior. But norms don’t exist in a vacuum; they are passed down and reinforced through countless interactions. For example, a first-year student might learn to respect a professor’s authority by noticing how others address them formally or by reading the syllabus and interpreting its tone. Similarly, students learn broader societal values—like the importance of hard work or independence—through their experiences both inside and outside the classroom.

Sometimes, this process involves significant change. Resocialization occurs when individuals must replace old behaviors with new ones to fit into a different social context. Consider an international student who arrives on campus and must adjust to a new language, customs, and expectations. They might unlearn certain habits—like standing close to someone while speaking—and adopt new ones, such as maintaining more personal space. Resocialization is also seen in structured environments like the military or rehabilitation programs, where individuals undergo deliberate efforts to adopt a new way of living. In both cases, socialization is not a one-time event but an ongoing process that shifts as we encounter new roles and environments.

At this point, it’s helpful to think about how sociology and psychology approach this topic. Sociology looks outward, focusing on how social structures and interactions shape individuals. A sociologist might ask how the college environment itself—through orientation sessions, peer networks, or classroom hierarchies—teaches students what it means to be a “successful” student. Psychology, by contrast, looks inward, examining how individual minds develop and process these changes. A psychologist might study how a student’s personality influences their ability to adapt to college life or how stress affects their learning.

To better understand this distinction, think about a student navigating group work in class. A psychologist might explore how the student’s anxiety impacts their ability to collaborate. A sociologist, however, would focus on how group dynamics, cultural expectations, or power structures influence how students engage with one another. Both perspectives are valuable, but sociology helps us zoom out and see the bigger picture of how individuals are shaped by the societies they live in.

Understanding socialization and its counterpart, resocialization, is the foundation for exploring identity, status, and roles, which are central to how we define ourselves and find our place in society. These concepts will help us unpack the ways in which socialization shapes not just what we do, but who we become.

Status and Role: Finding Our Place and Playing Our Part

Imagine walking into a busy cafeteria on your college campus. At one table, a group of students in athletic gear is chatting and laughing. Across the room, a professor is sitting with a colleague, deep in discussion. Nearby, a custodian is clearing trays while a line of students waits impatiently for their coffee orders. Each person in this scene occupies a unique status within the social system of the campus. Status is more than just a title; it is the position someone holds in relation to others.

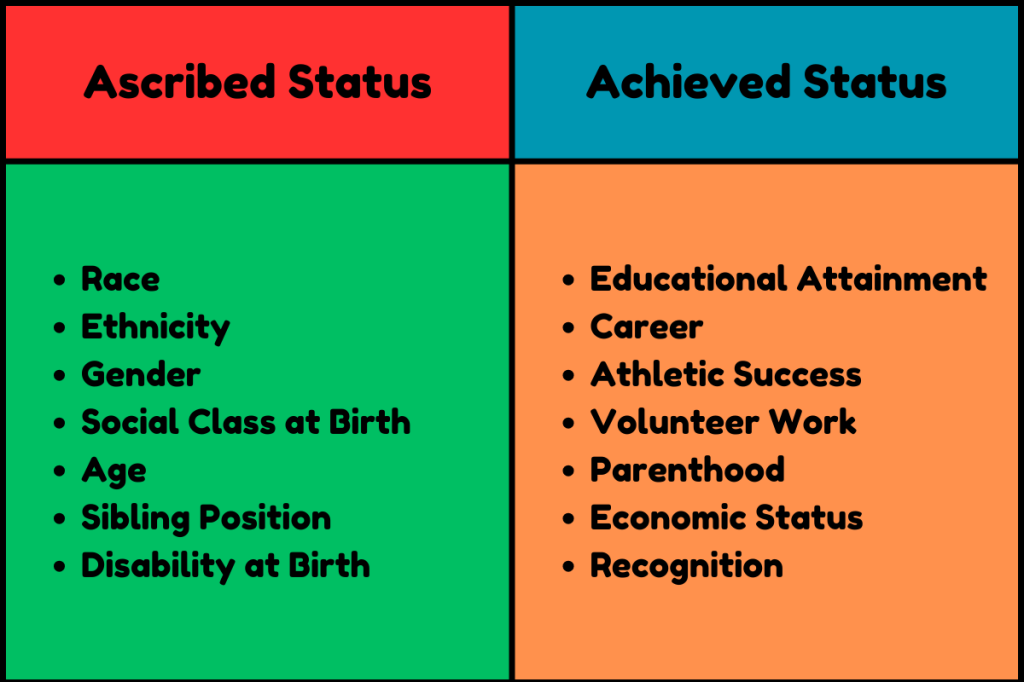

Statuses come in many forms. Some are assigned at birth or early in life. These are known as ascribed statuses. For instance, a person might be identified as a son, a daughter, or a sibling. Characteristics like race, ethnicity, and gender often fall into this category as well. Ascribed statuses are not chosen; they are given by circumstances and often influence how others perceive us from the start.

Other statuses are earned or chosen through effort, skill, or luck. These are called achieved statuses. A student’s role as captain of a sports team or a professor’s position in a department are examples of achieved statuses. Even being a college student is an achieved status, one that often comes with expectations about persistence, academic success, and eventually earning a degree. However, the line between ascribed and achieved statuses isn’t always clear. For instance, someone born into a wealthy family might achieve high social status more easily because of the advantages their ascribed status provides.

Statuses also carry varying levels of honor or prestige. In a college setting, professors might be seen as having higher status because of their expertise and authority, while students might hold less prestige as learners who are still developing their knowledge. Yet, within the student body, a senior preparing to graduate may hold higher status than a first-year student just starting out. This interplay of status shows how social systems constantly define and redefine our positions relative to others.

While statuses define our positions, roles define our actions. A role is the set of socially expected behaviors associated with a particular status. Think of a professor again. Their status as a professor positions them within the academic hierarchy, but their role involves teaching, mentoring, and conducting research. Similarly, a student’s role includes attending classes, completing assignments, and participating in campus life.

The relationship between status and role can be summarized in a simple phrase: “A person holds a status and plays a role.” For example, consider a student who has a part-time job on campus. They hold two statuses: student and employee. Each status comes with distinct roles. As a student, they might spend time studying and preparing for exams, while as an employee, they are expected to fulfill their work shifts and follow workplace policies. Balancing these roles can be challenging, especially when the demands of one status conflict with the expectations of another. Sociologists refer to this as role conflict.

To illustrate, imagine the student has a major project due the same week their supervisor schedules extra shifts at work. The pressure to perform well in both roles creates tension, highlighting how the expectations of our roles can sometimes clash. Even when roles don’t conflict, they can still be demanding. A college student might feel the weight of societal expectations to excel academically, contribute to their community, and maintain friendships, all while navigating personal growth.

Roles are not static. They adapt to circumstances and interactions. For instance, the behavior expected of a student in a classroom differs from what is expected at a party. Similarly, someone’s role as a sibling might shift as they grow older and take on new responsibilities within the family.

Together, status and role shape our daily lives and interactions. Status gives us a place within the social structure, while roles provide the script for how to act in that place. As we move through different settings, whether a college cafeteria, a classroom, or a workplace, we carry multiple statuses and play multiple roles, each contributing to the complex web of relationships that defines society.

Understanding status and role is essential to seeing how individuals connect to the broader social systems around them. From here, we can explore how these concepts intertwine with identity, examining how socialization helps us perform our roles and navigate the expectations tied to our statuses.

Identity: Understanding Who We Are and How We Are Seen

Who are you? It seems like a simple question, but the answer is anything but straightforward. You might say you are a student, an artist, a friend, or an athlete. These answers reflect parts of your identity, the complex combination of how you see yourself and how others perceive you. Identity is shaped by personal experiences, societal expectations, and the interplay between the two. It is what makes us unique as individuals and what connects us to the larger social world.

Self-identity is how you see yourself, the way you define who you are based on your own thoughts, feelings, and experiences. For example, you might think of yourself as a dedicated student who values hard work, or as someone who loves adventure and embraces risks. Self-identity reflects the characteristics and roles you emphasize when you think about who you are. It is deeply personal, often tied to the goals, values, and passions that matter most to you.

Think about an athlete who defines themselves through their commitment to their sport. They see themselves as disciplined, competitive, and driven. These qualities are central to how they view their own identity. However, self-identity is not static. It can change as people grow, face new experiences, and encounter different perspectives. For instance, the athlete might later identify more strongly as a coach, a parent, or a scholar, reflecting how identity evolves over time.

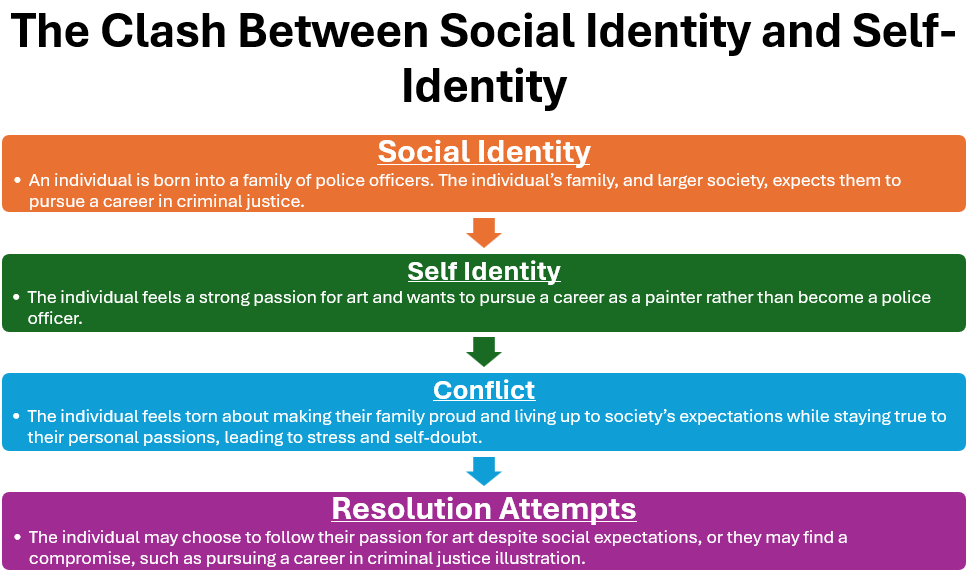

While self-identity focuses inward, social identity reflects how society sees you. This is shaped by external factors, including the statuses and roles you hold, as well as larger societal categories like race, gender, age, and class. Social identity highlights the way others define you, sometimes in ways that may not align with your own sense of self.

For example, the same athlete who identifies primarily with their role in sports might find that society focuses instead on their race or gender. A Latino athlete, for instance, might find that others emphasize their ethnicity or make assumptions about their background, even though they see their athletic ability as the most important part of their identity. This disconnect between self-identity and social identity can create tension, especially when societal perceptions carry stereotypes or expectations that feel limiting or inaccurate.

Social identity also shapes opportunities and challenges. Society’s perception of an individual can influence how they are treated, what resources are available to them, and how much recognition they receive for their achievements. For instance, a woman pursuing a career in engineering might see herself as ambitious and capable, but her social identity as a woman in a male-dominated field might subject her to biases or assumptions that challenge her ability to succeed.

The interaction between self-identity and social identity is at the heart of understanding who we are. Sometimes these two aspects align, creating a sense of harmony between how we see ourselves and how the world sees us. Other times, they are at odds, forcing individuals to navigate conflicts between their inner sense of self and external expectations.

Identity is both personal and social, shaped by the interplay of individual agency and societal influence. It evolves as we interact with others and respond to the contexts we live in. By examining identity, we begin to see how socialization shapes not only what we do, but also how we think about ourselves and how we are understood by others. This understanding lays the groundwork for exploring the complexities of human behavior and the ways individuals navigate their social worlds.

Types of Socialization

Now that we’ve identified what makes up the socialization process, let’s look at the different types of socialization. As a reminder, socialization is the process through which we learn societal norms, values, beliefs, and expectations. It is how we navigate the rules and behaviors that help us function in various settings, from the family to the workplace. While socialization occurs throughout life, the process can take different forms depending on where we are and what we are learning.

Primary Socialization begins at birth and continues through adolescence. It forms the foundation of everything we learn about how to live in society. For most people, this type of socialization takes place within the family. Parents teach children basic skills, such as how to speak, eat, and interact with others. For example, a child might learn to say “please” and “thank you” at the dinner table, a practice that reinforces the importance of politeness. Beyond the family, schools and religious institutions also play a role. A kindergarten teacher might teach children to share toys and follow rules, while a religious leader might introduce them to ideas about morality and community.

As we grow older, Secondary Socialization takes over. This type of socialization happens throughout our lives as we encounter new groups, settings, and situations. It allows us to adapt to environments beyond those we experienced in our childhood. Consider a high school graduate entering college for the first time. The norms they learned at home might not be sufficient to navigate their new environment. In college, they may learn to interact with professors, manage their time independently, or adapt to living with roommates. Similarly, starting a new job involves learning workplace norms, like how to interact with colleagues and what level of professionalism is expected.

Anticipatory Socialization occurs when we prepare for future roles. This process is often self-directed but can include guidance from others. For example, a student applying to medical school might shadow a doctor to understand what the profession entails. Similarly, someone preparing for parenthood might take classes on childbirth or read books about raising children. Anticipatory socialization helps individuals step into new roles with a sense of readiness and confidence.

Organizational Socialization takes place within institutions and organizations. This is when individuals learn the specific norms, values, and practices of a structured environment. For instance, someone starting a new job might attend a training program to understand the company’s policies and expectations. A new employee at a tech company might learn how to collaborate in team meetings or use specialized software. This type of socialization ensures that individuals can function effectively within a particular organization.

Forced Socialization is a process that occurs in environments referred to as “total institutions.” In these settings, individuals undergo resocialization through coercion, often adopting new norms, values, and customs. Examples of total institutions include prisons, mental hospitals, and the military. For instance, in basic training, military recruits might be required to abandon their previous ways of thinking and adopt strict discipline, teamwork, and obedience. Forced socialization often involves breaking down an individual’s existing identity and rebuilding it to align with the goals of the institution.

Socialization is also deeply influenced by factors such as gender, race, and class. These aspects of an individual’s identity shape the way they are socialized and how they see themselves within society. For example, a young girl might learn specific behaviors, attitudes, and expectations associated with femininity from her family and peers. Similarly, a person’s race can influence their experiences of socialization, as they may internalize both positive and negative messages about their racial identity based on how society treats them. Class also plays a significant role, as individuals from different socioeconomic backgrounds are socialized into distinct values, habits, and aspirations. A child from an affluent family might be exposed to norms that emphasize ambition and leadership, while a child from a working-class background might be socialized to value resilience and community.

Together, these types of socialization illustrate how we learn to navigate the many roles and identities we hold throughout life. They show that while socialization begins early, it never truly ends, as we continue to grow, adapt, and integrate into the social world around us.

Agents of Socialization

Socialization is not something we learn on our own. It is shaped by the people, groups, and institutions that influence how we understand the world and our place within it. These influences, known as agents of socialization, are the structures and relationships through which we acquire norms, values, and behaviors. They play a critical role in teaching us what is expected of us in society. Let’s explore some of the key agents of socialization and their impact.

The family institution is the first and often most significant agent of socialization. From birth, families provide the foundation for learning language, emotional expression, and cultural norms. Parents, guardians, and siblings teach children basic behaviors, such as how to eat, speak, and interact with others. For example, a child might learn to value punctuality because their parents emphasize being on time for meals or family gatherings. Family also shapes broader beliefs, such as attitudes toward education or religion, which often remain influential throughout a person’s life.

As children grow older, the educational institution becomes another central agent of socialization. Schools do more than teach academic subjects; they instill societal norms, such as respect for authority and the importance of hard work. For instance, a student might learn to raise their hand before speaking in class, reinforcing the idea that waiting one’s turn is important in group settings. Beyond formal lessons, schools also teach hidden lessons, such as how to navigate social hierarchies among peers or the importance of punctuality through structured schedules.

The religious institution is another agent of socialization that introduces individuals to moral and ethical values. Many people grow up attending religious services, where they learn principles about right and wrong, compassion, and community. For example, a child attending Sunday school might learn the importance of sharing by hearing parables or participating in group activities. Even for those who are not religious, these institutions often shape societal norms and provide a shared moral framework.

The political institution influences socialization by shaping individuals’ understanding of power, authority, and civic responsibility. From an early age, people are exposed to political values through family discussions, media coverage, or participation in activities such as voting drives. For example, a teenager might learn the importance of voting by watching their parents discuss and participate in elections.

Beyond political behaviors, individuals are also socialized into political groups and ideologies. Families often play a significant role in shaping early political identities, with many people adopting the political leanings of their parents or caregivers. For instance, someone raised in a household that regularly discusses progressive policies might be more inclined to identify with the Democratic Party, while someone raised in a household that values traditional conservative ideals might lean toward the Republican Party. Peer groups, educational experiences, and media further reinforce or challenge these political identities over time, showing how political socialization involves not only actions like voting but also the formation of deeper political affiliations and beliefs.

The economic institution plays a critical role in socialization, particularly through the workplace. Entering a job requires learning new norms, values, and expectations tied to professional conduct. For instance, a new employee might learn the importance of teamwork by participating in collaborative projects or the value of punctuality by adhering to strict work schedules. The workplace also teaches individuals how to navigate hierarchies and adapt to the culture of their organization.

Outside of formal institutions, peer groups serve as a powerful agent of socialization, especially during adolescence. Peer groups offer a sense of belonging and provide a space where individuals can experiment with identity and learn social norms. For example, a group of high school friends might encourage each other to dress a certain way, speak in specific slang, or share interests in music or sports. While these interactions may seem superficial, they often reinforce deeper social values, such as loyalty, trust, and group conformity.

Finally, mass media, including social media, has become one of the most pervasive agents of socialization in modern society. Television, movies, and news outlets shape how people view the world and their place in it. For instance, a child watching a superhero movie might learn ideas about bravery or justice, while an adult following news coverage might develop opinions about current events.

Social media, in particular, has amplified the role of mass media in socialization. Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter expose individuals to a constant stream of images, opinions, and social norms. These platforms shape not only how people see the world but also how they see themselves. For example, a teenager scrolling through Instagram might compare themselves to influencers, adopting trends in fashion or fitness based on what they see. Social media also creates new norms for communication, such as the expectation to maintain a curated online presence or to respond quickly to messages.

Each of these agents of socialization contributes to the process of learning and adapting to societal expectations. Together, they help individuals navigate the complexities of life, teaching them the skills, values, and behaviors needed to participate in their communities. By understanding these agents, we gain insight into how society shapes individuals and how individuals, in turn, shape society.

Sociological Theories in Action: Examining Social Media’s Role in Shaping Beauty Standards

Social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok have become powerful agents of socialization, shaping how individuals see themselves and understand societal norms. Unlike traditional media, social media is interactive, allowing users to engage with and contribute to the content that informs these norms. Beauty standards, in particular, are actively constructed and reinforced through the endless stream of curated images, viral trends, and influencer promotions. An article in The New York Times, titled “Instagram Has Become a Body-Image Battleground,” highlights how augmented reality filters on Instagram play a critical role in this process. These filters smooth skin, brighten eyes, and sculpt features, creating a version of beauty that is both aspirational and unattainable, socializing users into prioritizing flawless appearance.

This socialization process occurs through the constant interaction between users and content. Beauty influencers, for example, share skincare routines, promote specific products, and participate in viral challenges, presenting themselves as role models for idealized beauty. Followers engage by liking, commenting, and mimicking these practices, normalizing certain beauty standards while embedding them into collective understandings of attractiveness. Over time, individuals internalize these norms, shaping their self-perception and behaviors. While social media can foster creativity and community, it often leads to negative consequences, such as body dissatisfaction and anxiety, as users compare themselves to curated and edited representations of others.

The dual impact of social media on beauty standards highlights its complex role in the socialization process. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok simultaneously empower users to create content and reinforce systemic beauty norms. By examining these dynamics through the lenses of symbolic interactionism, structural functionalism, and conflict theory, we can better understand the ways social media shapes not only individual identities but also societal values.

Symbolic Interactionism: Social Media and the Construction of Beauty

Symbolic interactionism focuses on the meanings individuals attach to symbols and interactions. From this perspective, social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok are spaces where people collectively construct and negotiate the meaning of beauty.

When users interact with beauty-related content, they engage with a symbolic world where filters, makeup tutorials, and body poses signify attractiveness and desirability. For example, a viral TikTok trend promoting a specific skincare product might symbolize self-care and status. As users participate by replicating these trends or endorsing them through likes and comments, they reinforce the shared meaning of these symbols.

The process of creating and sharing content also allows individuals to shape their self-presentation. A person might carefully choose an image that aligns with beauty norms to gain validation from their followers, such as likes or positive comments. Over time, this interaction between users and content shapes both individual self-concepts and collective definitions of beauty. Symbolic interactionism highlights how social media users are not passive recipients but active participants in the socialization process, negotiating the meanings attached to beauty and identity.

Structural Functionalism: Social Media and Social Stability

Structural functionalism views society as a system where various parts work together to maintain stability and cohesion. From this perspective, social media’s promotion of beauty standards serves a functional role by reinforcing shared norms and values related to appearance.

Platforms like Instagram and TikTok can be seen as modern tools for maintaining social order by encouraging conformity to societal expectations. For instance, beauty content might promote routines that symbolize discipline, such as daily skincare regimens or fitness challenges. These practices align with broader societal values, such as health, self-care, and productivity, contributing to a sense of cohesion and shared purpose.

At the same time, the functionalist perspective recognizes that social media also facilitates social integration by connecting individuals who share similar interests. Communities centered on beauty, such as makeup enthusiasts or fitness influencers, provide spaces where individuals can bond over shared values and practices. These connections reinforce societal norms and create a sense of belonging.

However, structural functionalism also raises questions about the dysfunctions of social media. While promoting beauty standards may contribute to social cohesion, it can also lead to negative outcomes, such as body dissatisfaction or exclusion of those who do not conform to these ideals. These dysfunctions highlight the complex role of social media in balancing individual needs and societal stability.

Conflict Theory: Social Media and Power Dynamics

Conflict theory emphasizes the role of power, inequality, and competition in shaping society. From this perspective, social media’s promotion of beauty standards reflects and reinforces existing inequalities, particularly those related to gender, race, and class.

Platforms like Instagram and TikTok are dominated by influencers and corporations who profit from perpetuating narrow beauty ideals. These standards often privilege whiteness, thinness, and wealth, marginalizing individuals who do not fit these criteria. For example, beauty influencers often partner with luxury brands, showcasing expensive products that are inaccessible to many. This dynamic reinforces class divisions by associating beauty with financial privilege.

Moreover, social media platforms themselves profit from users’ insecurities. Algorithms amplify content that garners engagement, which often includes idealized or unrealistic images. The resulting cycle—where users internalize beauty standards, seek validation through conformity, and consume products to achieve these ideals—benefits corporations while exacerbating social inequalities.

Conflict theory also highlights the resistance that emerges in response to these power dynamics. For instance, body positivity and inclusivity movements challenge the dominant beauty norms by promoting diverse representations of beauty. These movements reflect the ongoing struggle between marginalized groups seeking representation and the forces that maintain existing hierarchies.

Theories of Socialization: Understanding How We Learn to Be Social

Socialization is not just about what we learn; it is also about how we learn. Over the years, theorists have debated how individuals internalize societal norms, values, and behaviors. These debates reveal the complex interplay between individual development and social influences. Let’s examine some of the most influential perspectives, beginning with the social dimensions of identity before turning to the cognitive processes that underlie socialization.

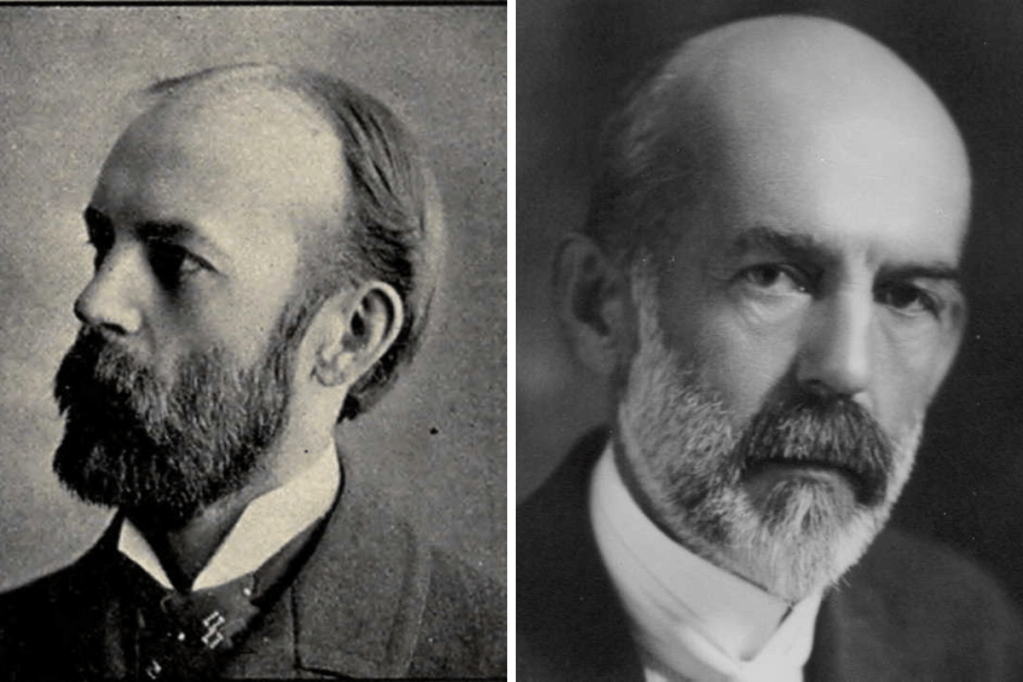

Charles Horton Cooley and George Herbert Mead: The Social Dimensions of Identity

Charles Horton Cooley (1864–1929) and George Herbert Mead (1863–1931) were prominent American sociologists whose work shaped the understanding of socialization and identity. Both men were part of the Chicago School of Sociology, an intellectual movement that emphasized the role of social interaction in shaping human behavior. Cooley was particularly interested in the ways individuals perceive themselves through their relationships with others, while Mead focused on the development of the self through social experiences.

Cooley introduced the concept of the looking-glass self, which explains how individuals form their sense of self through interactions with others. According to Cooley, people imagine how they appear to others, interpret how others judge them, and experience an emotional response to those imagined judgments. For example, a student might feel pride if they believe their professor sees them as hardworking, or embarrassment if they imagine the professor views them as inattentive. This process of reflection helps shape how individuals see themselves.

Building on this idea, George Herbert Mead explored the development of the self through distinct stages of social interaction. Mead argued that individuals are not born with a sense of self but gradually develop it through their interactions with others. In early childhood, during what Mead called the preparatory stage, children mimic the behaviors, words, and gestures of those around them without fully understanding their meaning. For example, a toddler might repeat a parent’s words or copy their actions, such as pretending to talk on a phone. As children grow, they enter the play stage, where they begin to take on specific roles during play, such as pretending to be a teacher, doctor, or parent. This stage reflects their growing ability to imagine themselves in the roles of others and understand the expectations associated with those roles. Eventually, children reach the game stage, where they develop the ability to take on multiple roles and understand the broader rules that govern social interactions. For instance, a child playing on a sports team must recognize how their position relates to the roles of their teammates, demonstrating an awareness of the larger group dynamic. These stages collectively help individuals develop a sense of self as they learn to see themselves from the perspective of others.

Finally, Mead described the game stage, where children learn to navigate multiple roles simultaneously and understand the rules that govern social interactions. For instance, a child playing on a sports team must not only consider their own position but also how their actions affect their teammates and the overall game. At this stage, individuals internalize what Mead called the “generalized other,” or the expectations and norms of society as a whole.

Together, Cooley and Mead show how social interaction is central to the development of identity. While Cooley focuses on the reflective process of imagining how others perceive us, Mead emphasizes the active role of taking on and internalizing societal roles. Both perspectives highlight the deeply social nature of selfhood and the importance of interaction in shaping who we are.

As Cooley and Mead revealed how identity emerges through interaction, other theorists turned their attention to the internal processes of development. Among them was Jean Piaget, whose groundbreaking research explored how individuals acquire the mental tools needed to navigate the social world.

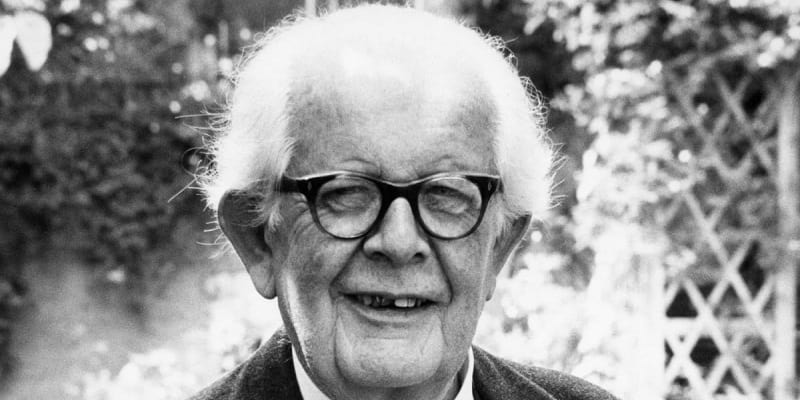

Jean Piaget: Cognitive Development and Socialization

Jean Piaget (1896–1980) was a Swiss psychologist known for his pioneering work on cognitive development. Trained in biology and philosophy, Piaget became fascinated with how children learn and process information. His observations of children led him to develop one of the most influential theories of child development, emphasizing the stages through which individuals acquire the mental tools to navigate the world.

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development identifies distinct stages that correspond to different ages. The first stage, known as the sensorimotor stage, occurs from birth to about two years old. During this period, infants explore their environment through their senses and develop basic motor skills. For example, a baby might learn that shaking a rattle produces a sound, demonstrating the connection between action and result.

The second stage, the preoperational stage, takes place between ages two and seven. Children in this stage begin to develop symbolic thinking, such as using words or drawings to represent objects. For instance, a child might pretend that a stick is a sword, engaging in imaginative play that reflects their growing understanding of the world.

The concrete operational stage, which occurs between ages seven and eleven, marks a shift toward logical thinking. At this stage, children can understand concepts like cause and effect and are able to grasp the perspectives of others. For example, they might learn to share with peers during group activities at school, recognizing the fairness of taking turns.

Finally, the formal operational stage emerges around age twelve and continues into adulthood. In this stage, individuals develop the ability to think abstractly and reason about hypothetical scenarios. For instance, a teenager debating ethical questions in a classroom discussion demonstrates the advanced cognitive skills associated with this stage.

Piaget’s work highlights the importance of cognitive development in socialization, showing how individuals gradually develop the mental tools to understand and navigate the world around them.

While Piaget’s work emphasized universal stages of development, Lev Vygotsky offered a different perspective, focusing on the critical role of culture and social interaction in shaping how individuals learn and grow.

Lev Vygotsky: Sociocultural Theory of Development

Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) was a Russian psychologist whose sociocultural theory of development emphasized the critical role of social and cultural contexts in learning. Trained in law, history, and philosophy, Vygotsky turned to psychology in the 1920s, where he sought to understand how individuals develop through interactions with their environments. Unlike Piaget, who focused on universal stages of development, Vygotsky argued that learning is inherently social and varies across cultural contexts.

One of Vygotsky’s central concepts is the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which refers to the range of tasks a child can perform with assistance but not yet independently. For example, a child learning to solve a math problem might initially rely on a teacher’s explanation or collaborate with a peer. Over time, they internalize these strategies and are able to solve similar problems on their own.

Vygotsky also introduced the idea of scaffolding, where more experienced individuals provide structured support to help learners move through the ZPD. For instance, a parent teaching a child to tie their shoes might initially guide the child’s hands, then gradually reduce their assistance as the child becomes more confident.

Language, for Vygotsky, is a critical cultural tool that facilitates cognitive development. Through conversations and storytelling, children learn not only vocabulary but also the ways of thinking and problem-solving valued by their culture. For example, a child raised in a community that values collective responsibility might learn to prioritize group goals through discussions with family members.

Vygotsky’s theory underscores the importance of social interaction and cultural context in shaping how individuals learn and grow.

***

Although Cooley, Mead, Piaget, and Vygotsky approached socialization from different angles, their theories collectively reveal the complexity of this process. Cooley and Mead emphasize the deeply social nature of identity, showing how individuals develop a sense of self through interaction and reflection. Piaget’s work highlights the stages of cognitive development that enable individuals to understand and navigate the world, while Vygotsky expands this understanding by focusing on the critical role of social and cultural influences in learning.

Together, these perspectives show that socialization is both an individual and collective process, involving the development of cognitive abilities, the internalization of social roles, and the influence of cultural tools. By integrating these theories, we gain a richer understanding of how individuals learn to participate in and shape their social worlds.

Conclusion

Socialization is the invisible thread that weaves individuals into the fabric of society. It begins in our earliest interactions with family and continues throughout our lives as we encounter new roles, relationships, and institutions. Through the processes of primary and secondary socialization, we internalize societal norms and develop our identities. Agents of socialization such as family, schools, peer groups, and social media provide the frameworks through which we learn how to navigate the world. Each agent plays a unique role, influencing not only how we behave but also how we perceive ourselves and others.

Theories of socialization, from Cooley and Mead’s focus on identity to Piaget and Vygotsky’s insights into cognitive and cultural development, reveal the multifaceted nature of this process. Social media, as explored in this chapter, demonstrates how the modern world adds complexity to socialization, serving as both a space for creativity and a battleground for contested norms. By synthesizing these perspectives, we see that socialization is not a one-way process but a dynamic interaction between individuals and the society they inhabit.

As we move forward, understanding socialization helps us see the profound connections between individual behavior and larger social patterns. It reminds us that while we are shaped by society, we also have the power to influence and reshape it, one interaction at a time.

Key Terms

Achieved Status: A status that an individual earns or chooses, reflecting personal skills, abilities, or efforts.

- Example: Becoming a college graduate is an achieved status because it requires effort and dedication.

Anticipatory Socialization: The process of preparing for future roles by adopting the values, behaviors, or attitudes associated with those roles.

- Example: A student interning at a company learns workplace norms in preparation for a full-time job.

Ascribed Status: A status that an individual is born into or assigned involuntarily.

- Example: Being a sibling or being categorized by race are ascribed statuses.

Concrete Operational Stage: Jean Piaget’s stage (ages 7–11) in which children develop logical thinking and understand cause-and-effect relationships.

- Example: A child learning to share during group activities demonstrates an understanding of fairness.

Economic Institution (Agent of Socialization): The systems and structures that manage the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services, shaping norms related to work and economic participation.

- Example: Starting a job teaches norms like punctuality, teamwork, and professional behavior, integrating individuals into the workforce and broader economy.

Educational Institution (Agent of Socialization): Schools and other formal learning environments that socialize individuals by teaching societal norms, values, and skills necessary for functioning within society.

- Example: A student learns discipline, cooperation, and respect for authority through structured classroom environments.

Family Institution (Agent of Socialization): The primary context for early socialization, where individuals first learn societal norms, values, and behaviors.

- Example: Parents teaching children to say “please” and “thank you” is an example of the family shaping politeness and manners.

Formal Operational Stage: Jean Piaget’s stage (age 12 and beyond) in which individuals develop abstract thinking and reasoning about hypothetical scenarios.

- Example: A teenager debating ethical dilemmas in a philosophy class demonstrates this stage.

Forced Socialization: A process that occurs in total institutions where individuals are resocialized to adopt new norms, values, and behaviors.

- Example: Military boot camp involves forced socialization to instill discipline and teamwork.

Game Stage: The final stage of George Herbert Mead’s theory where children develop the ability to understand and coordinate multiple roles within a structured set of rules, reflecting a more comprehensive awareness of social dynamics.

- Example: A child playing soccer recognizes their role as a defender while also understanding how it relates to their teammates’ roles, like the goalkeeper or forward.

Generalized Other: George Herbert Mead’s concept of the internalized attitudes, expectations, and norms of society that guide individual behavior.

- Example: A person refrains from littering because they understand societal norms about cleanliness.

Identity: How individuals define themselves, encompassing both self-identity and social identity.

- Example: Someone may see themselves as an artist (self-identity) while society views them as a student (social identity).

Looking-Glass Self: Charles Horton Cooley’s concept that individuals form their self-identity based on how they think others perceive them.

- Example: A student might feel proud after receiving positive feedback from a teacher, shaping their view of themselves as hardworking.

Mass Media (Agent of Socialization): Communication platforms like television, social media, and news outlets that socialize individuals by transmitting societal norms, values, and behaviors to broad audiences.

- Example: TikTok influences trends in beauty standards through viral content, shaping perceptions of appearance and self-presentation.

Organizational Socialization: The process of learning the norms, values, and practices of a specific institution or workplace, integrating individuals into its structure.

- Example: A new employee attending a company orientation learns about workplace expectations and how to fit into the organization’s culture.

Peer Groups (Agent of Socialization): Groups of individuals, often of similar age, that socialize members by influencing their behaviors, norms, and values.

- Example: Teenagers may adopt specific slang or fashion styles to fit in with their friend group.

Play Stage: The second stage of George Herbert Mead’s theory where children begin to take on specific roles during play, showing an understanding of individual roles they observe in their environment.

- Example: A child pretending to be a teacher and imitating classroom activities they’ve observed, such as giving instructions to an imaginary class.

Political Institution (Agent of Socialization): The systems and structures that govern society, socializing individuals into roles related to power, governance, and civic responsibility.

- Example: Voting in an election socializes individuals into understanding democratic participation and civic duties.

Preoperational Stage: Jean Piaget’s stage (ages 2–7) in which children develop symbolic thinking and imagination.

- Example: A child pretending a stick is a sword demonstrates symbolic play.

Preparatory Stage: The initial stage in George Herbert Mead’s theory of self-development where young children imitate the actions and words of others without understanding their meaning.

- Example: A toddler waving goodbye after seeing a parent do so, even though they may not fully grasp the social meaning behind the gesture.

Primary Socialization: The initial socialization process that occurs from birth through early childhood, primarily within the family.

- Example: A child learns language and basic manners from their parents.

Religious Institution (Agent of Socialization): Faith-based organizations that socialize individuals by teaching moral and ethical values and creating a sense of community.

- Example: Attending Sunday school introduces children to principles like compassion, forgiveness, and community belonging.

Resocialization: The process by which individuals discard old behaviors and adopt new ones, often within a controlled environment.

- Example: Someone moving into a rehabilitation center learns new habits to replace harmful ones.

Role: The behaviors expected of an individual based on their status in society.

- Example: A teacher’s role involves educating students and maintaining a professional demeanor.

Role Conflict: The tension that occurs when the expectations of two or more roles held by an individual clash.

- Example: A working parent may experience role conflict when their job requires overtime on the same evening their child has a school event.

Scaffolding: Lev Vygotsky’s concept of providing structured support to help learners master tasks within their Zone of Proximal Development.

- Example: A parent helping a child tie their shoes by guiding their hands is scaffolding.

Secondary Socialization: Socialization that occurs later in life through new roles, settings, or groups.

- Example: A person learns workplace norms after starting their first job.

Self-Identity: How individuals see themselves, based on their personal traits, values, and experiences.

- Example: Someone might see themselves as an adventurous person based on their love of travel.

Sensorimotor Stage: Jean Piaget’s stage (birth to age 2) in which infants learn through sensory experiences and motor activities.

- Example: A baby shaking a rattle to hear its sound demonstrates learning through action.

Social Identity: How society perceives and categorizes an individual, often based on group membership.

- Example: A person may identify as an athlete, but society may categorize them based on their race or gender.

Socialization: The lifelong process through which individuals learn norms, values, and behaviors appropriate to their society.

- Example: Children learn to share and cooperate through play with others.

Status: A position an individual holds in a social system, which can be ascribed or achieved.

- Example: Being a parent is a status within a family system.

Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD): Lev Vygotsky’s concept of the range of tasks a person can accomplish with help but not yet independently.

- Example: A child learning to read may initially require a teacher’s guidance before mastering it on their own.

Reflection Questions

- How do platforms like Instagram or TikTok act as agents of socialization, and what messages do they send about beauty, success, or social norms?

- How does socialization differ based on factors like gender, race, or social class, and why is it important to recognize how background shapes expectations and behavior?

- What is the difference between social identity and self-identity, and how can tension between the two influence how people think, act, or present themselves?

- How do different agents of socialization, such as family, peers, education, and media, shape us at different stages of life, and why might their influence change over time?