Short Biography

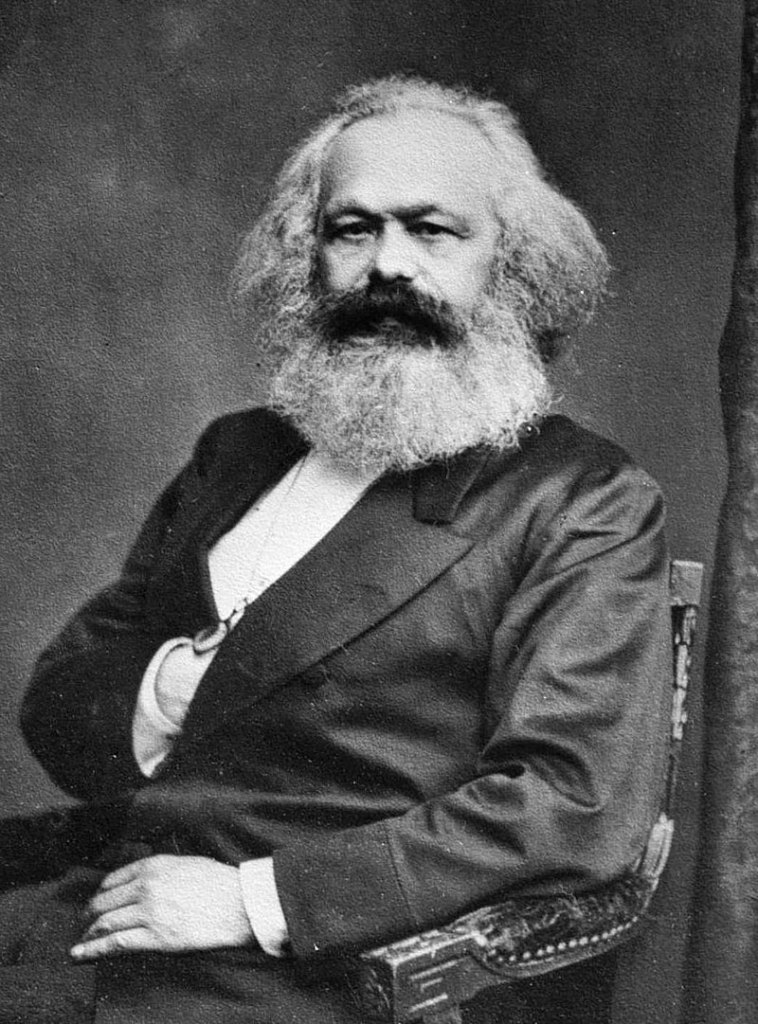

Karl Marx, a figure who left an indelible mark on political economy and revolutionary thought, never actually identified himself as a sociologist. He was born in 1818 in Trier, Prussia (now Germany), into a family with a lineage of rabbis. Despite this religious background, Marx’s father, a lawyer by profession, converted himself and his family to Protestantism when Marx was just seven years old. This conversion was largely driven by the prevailing prejudice and discrimination against Jews at the time.

Marx’s academic journey began at the University of Bonn, but his tenure there was short-lived. He was expelled in his second semester, a move that reflected his burgeoning radicalism and nonconformity. During his university years, Marx became involved with the Young Hegelians, a group of radical thinkers who drew inspiration from the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. The Young Hegelians were known for their critical approach to philosophy, politics, and religion, which significantly influenced Marx’s own ideological development.

Marx’s outspoken nature and critical writings soon put him at odds with the authorities. In 1843, his criticism of the Prussian government led to his expulsion from the country. Seeking refuge, Marx moved to Paris, France, where he encountered Friedrich Engels. This meeting marked the beginning of a lifelong partnership and collaboration that would profoundly impact socialist theory and practice. During his time in Paris, Marx became a key figure in the Commune Movement, a revolutionary socialist group.

However, his stay in France was not to last. In 1845, following a crackdown on the Commune Movement by the Parisian police, Marx and his family were forced into exile. They eventually settled in Piccadilly Circus, a poverty-stricken area of London, England. Despite coming from affluent backgrounds, Marx and his wife Jenny lived in poverty for most of their lives. Tragically, this hardship took its toll on their family, with only four of their eight children surviving into adulthood.

In London, Marx devoted most of his time to extensive reading and writing in the city’s library. He was an active contributor to various activist movements, most notably the First International, an international socialist organization. Despite living in poverty, Marx’s influence grew steadily. His writings, including those in the New York Daily Tribune, even reached and influenced figures such as President Abraham Lincoln. However, fame did not translate into financial stability, and Marx died in poverty in March 1883.

Marx’s legacy is complex and multifaceted. While he is primarily known for his contributions to political economy and revolutionary socialism, his ideas have had a profound and lasting impact on various fields, including sociology. His theories about class struggle, capitalism, and historical materialism continue to influence academic and political discourse worldwide.

Historical Materialism and the Base-Superstructure Relationship

Central to Marx’s theories is the concept of historical materialism, which posits that the economic base of a society fundamentally determines its societal structure and cultural practices. According to Marx, each socio-economic stage—whether it be slavery, feudalism, or capitalism—contains internal contradictions that create tensions and conflicts, driving the progression from one stage to the next. This process is not smooth but is marked by revolutions and radical shifts in power dynamics, leading to the evolution of societal systems.

The economic base, or mode of production, includes two key components:

- Productive Forces: This encompasses all the labor, tools, factories, machinery, raw materials, etc., necessary for producing goods and services.

- Relations of Production: This refers to the social and technical relationships people enter into as part of the production process, including property relations, laws, and worker associations.

Marx argued that the economic base shapes all other aspects of society, which he referred to as the superstructure. The superstructure includes institutions like politics, religion, education, and family. These institutions are not independent but are heavily influenced by the economic base, which dictates the conditions and relations within a society. Let’s look at how this relationship plays out in the next section.

Examples of the Base-Superstructure Relationship

Education System

In a capitalist society, the education system can be seen as part of the superstructure. The economic base—capitalism—requires a workforce with certain skills and knowledge to operate efficiently. Therefore, the education system is structured to produce workers who are trained and socialized to fit into the capitalist economy. Schools emphasize punctuality, discipline, and specialized skills, preparing students to take on roles that support the capitalist mode of production. For instance, business and technical courses are often prioritized over subjects like art or philosophy because they are deemed more directly beneficial to economic productivity.

Legal System

The legal system in a society is another element of the superstructure influenced by the economic base. In a capitalist economy, laws are often created to protect private property and capitalist interests. Intellectual property laws, for instance, ensure that businesses and individuals can own and profit from their ideas and inventions, thus encouraging innovation within the capitalist framework. Labor laws, while sometimes protecting worker rights, often balance these protections with the interests of employers to maintain a stable and productive workforce. This legal framework supports the capitalist mode of production by maintaining order and protecting the interests of the bourgeoisie.

The Family

Family structures and norms can also be influenced by the economic base. In a capitalist society, the nuclear family model (comprising two parents and their children) often reflects and supports the needs of the economy. This family structure provides a stable environment for raising future workers and consumers. Additionally, the traditional gender roles within this family model—where men are often seen as breadwinners and women as caregivers—support the capitalist system by ensuring a reliable workforce and a domestic sphere that supports the reproduction of labor. These roles, though increasingly challenged, have historically helped maintain the capitalist economic structure.

Conclusion

By understanding historical materialism and the base-superstructure relationship, we gain insight into Marx’s analysis of societal development and the underlying forces that drive historical change. These concepts illustrate how the economic base influences various societal institutions and cultural practices, shaping the superstructure in ways that support and perpetuate the dominant mode of production. This framework helps explain how changes in the economic base—such as the transition from feudalism to capitalism—can lead to significant societal transformations. Marx’s theories remain influential in contemporary discussions of sociology, economics, and political theory, providing a critical lens through which to examine the complexities of societal evolution.